General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region Forums'It's a powerful feeling': the Indigenous American tribe helping to bring back buffalo

A trio of bison has gathered around a fourth animal’s carcass, and Jimmy Doyle is worried.

“I really hope we’re not on the brink of some disease outbreak,” said Doyle, who manages the Wolakota Buffalo Range here in a remote corner of south-western South Dakota in one of the country’s poorest counties. The living bison sidle away as Doyle inspects the carcass, which is little more than skin and bones after coyotes have scavenged it.

“If you don’t catch them immediately after they’ve died, it’s pretty hard to say what happened,” he said.

So far, at least, the Wolakota herd has avoided outbreaks as it pursues its aim of becoming the largest Indigenous American-owned bison herd. In the two years since the Rosebud Sioux tribe started collecting the animals on the 28,000-acre range in the South Dakota hills, the herd has swelled to 750 bison. The tribe plans to reach its goal of 1,200 within the year.

“I thought we had an aggressive timeline on it, but the thing’s gotten a lot of support,” said Clay Colombe, CEO of the Rosebud tribe’s economic development agency. “It’s been a snowball in a good way.”

With their eyes on solving food shortages and financial shortfalls, restoring ecosystems and bringing back an important cultural component, dozens of indigenous tribes have been growing bison herds. Tribes manage at least 55 herds across 19 states, said Troy Heinert, executive director of the InterTribal Buffalo Council.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/feb/20/its-a-powerful-feeling-the-indigenous-american-tribe-helping-to-bring-back-buffalo

crickets

(25,952 posts)Judi Lynn

(160,450 posts)Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed

The Transcontinental Railroad connected East and West—and accelerated the destruction of what had been in the center of North America

Gilbert King

July 17, 2012

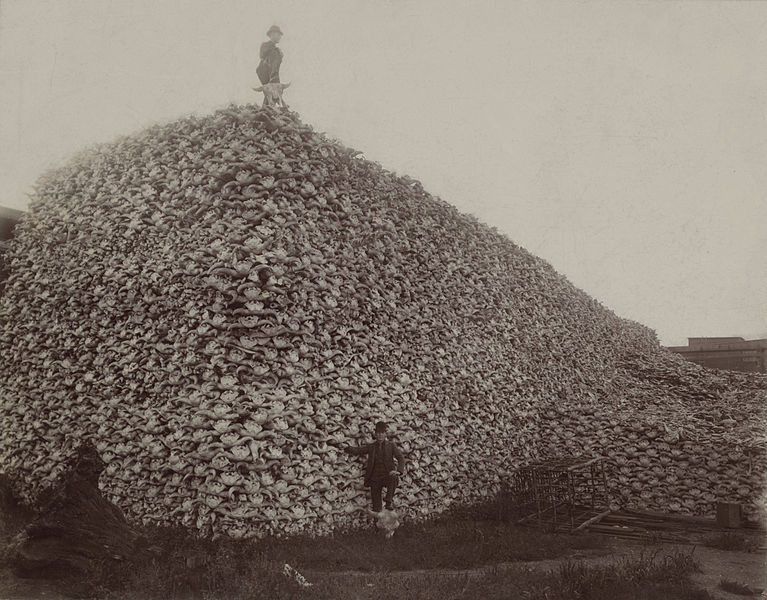

A pile of American bison skulls in the mid-1870s. Photo: Wikipedia

. . .

The Army’s troops were well equipped for fighting against conventional enemies, but the guerrilla tactics of the Plains tribes confounded them at every turn. As the railways expanded, they allowed the rapid transport of troops and supplies to areas where battles were being waged. Sheridan was soon able to mount the kind of offensive he desired. In the Winter Campaign of 1868-69 against Cheyenne encampments, Sheridan set about destroying the Indians’ food, shelter and livestock with overwhelming force, leaving women and children at the mercy of the Army and Indian warriors little choice but to surrender or risk starvation. In one such surprise raid at dawn during a November snowstorm in Indian Territory, Sheridan ordered the nearly 700 men of the Seventh Cavalry, commanded by George Armstrong Custer, to “destroy villages and ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and to bring back all women and children.” Custer’s men charged into a Cheyenne village on the Washita River, cutting down the Indians as they fled from lodges. Women and children were taken as hostages as part of Custer’s strategy to use them as human shields, but Cavalry scouts reported seeing women and children pursued and killed “without mercy” in what became known as the Washita Massacre. Custer later reported more than 100 Indian deaths, including that of Chief Black Kettle and his wife, Medicine Woman Later, shot in the back as they attempted to ride away on a pony. Cheyenne estimates of Indian deaths in the raid were about half of Custer’s total, and the Cheyenne did manage to kill 21 Cavalry troops while defending the attack. “If a village is attacked and women and children killed,” Sheridan once remarked, “the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack.”

The Transcontinental Railroad made Sheridan’s strategy of “total war” much more effective. In the mid-19th century, it was estimated that 30 milion to 60 million buffalo roamed the plains. In massive and majestic herds, they rumbled by the hundreds of thousands, creating the sound that earned them the nickname “Thunder of the Plains.” The bison’s lifespan of 25 years, rapid reproduction and resiliency in their environment enabled the species to flourish, as Native Americans were careful not to overhunt, and even men like William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who was hired by the Kansas Pacific Railroad to hunt the bison to feed thousands of rail laborers for years, could not make much of a dent in the buffalo population. In mid-century, trappers who had depleted the beaver populations of the Midwest began trading in buffalo robes and tongues; an estimated 200,000 buffalo were killed annually. Then the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad accelerated the decimation of the species.

Massive hunting parties began to arrive in the West by train, with thousands of men packing .50 caliber rifles, and leaving a trail of buffalo carnage in their wake. Unlike the Native Americans or Buffalo Bill, who killed for food, clothing and shelter, the hunters from the East killed mostly for sport. Native Americans looked on with horror as landscapes and prairies were littered with rotting buffalo carcasses. The railroads began to advertise excursions for “hunting by rail,” where trains encountered massive herds alongside or crossing the tracks. Hundreds of men aboard the trains climbed to the roofs and took aim, or fired from their windows, leaving countless 1,500-pound animals where they died.

Harper’s Weekly described these hunting excursions:

Nearly every railroad train which leaves or arrives at Fort Hays on the Kansas Pacific Railroad has its race with these herds of buffalo; and a most interesting and exciting scene is the result. The train is “slowed” to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, and open from the windows and platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish. Frequently a young bull will turn at bay for a moment. His exhibition of courage is generally his death-warrant, for the whole fire of the train is turned upon him, either killing him or some member of the herd in his immediate vicinity.

Hunters began killing buffalo by the hundreds of thousands in the winter months. One hunter, Orlando Brown brought down nearly 6,000 buffalo by himself and lost hearing in one ear from the constant firing of his .50 caliber rifle. The Texas legislature, sensing the buffalo were in danger of being wiped out, proposed a bill to protect the species. General Sheridan opposed it, stating, ”These men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

More:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-the-buffalo-no-longer-roamed-3067904/

~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~

Genocide by Other Means: U.S. Army Slaughtered Buffalo in Plains Indian Wars

Buffalo were their lifeline—the Indians had a symbiotic relationship with them, and always honored the mighty beasts for the many blessings they provided.

ADRIAN JAWORT

UPDATED:SEP 13, 2018

ORIGINAL:SEP 24, 2017

As long as the North American buffalo roamed free and bountiful, the Plains Indians were able to remain sovereign. Buffalo were their lifeline—the Indians had a symbiotic relationship with them, and always honored the mighty beasts for the many blessings they provided. “The creation stories of where buffalo came from put them in a very spiritual place among many tribes,” said University of Montana anthropology and Native American studies professor S. Neyooxet Greymorning. “The buffalo crossed many different areas and functions, and it was utilized in many ways. It was used in ceremonies, as well as to make tipi covers that provided homes for people, utensils, shields, weapons and parts were used for sewing with the sinew.”

For several millennia, both the buffalo and the Plains Indians prospered. Estimates put the peak bison population, during the mid-1800s, near 60 million, but based on the “carrying capacity” of the Great Plains, Temple University history professor Andrew Isenberg, author of The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750-1920, believes the number was closer to 30 million. He explains that estimates that went as high as 100 million came from travelers on the plains who saw the heaviest congregations of herds during their summer mating season. “Those observers assumed that such large herds were spread throughout the Plains throughout the year,” he said. “But in other seasons, when the grasses were thin, the bison dispersed into small foraging herds.” The bison population also fluctuated depending on a variety of non-human factors like wolves and harsh weather conditions.

As the U.S. government and its restless people looked to expand westward after the Civil War, they started to infringe upon Indian lands. During the Plains Indian Wars, as the U.S. Army attempted to drive Indians off the Plains and into reservations, the Army had little success because the warriors could live off the land and elude them—wherever the buffalo flourished, the Indians flourished. But pressure on the Army to contain the Indians increased in the 1860s when gold was discovered in the Montana Territory, and part of what is now eastern Wyoming became the route of the Bozeman Trail, the quickest way to get to the mines in Montana. This trail cut through sacred ground for the Sioux, as well as their prime hunting grounds—the “best game country in the world,” according to one veteran trapper. The Sioux regularly attacked travelers on the Bozeman Trail, and Army forts were set up to protect travelers through the Powder River Basin. During the Indians’ clashes with settlers, prospectors and U.S. Cavalry to protect a last bastion of their food supply in what became known as Red Cloud’s War, U.S. Army Captain Fetterman bragged, “With 80 men I could ride through the whole Sioux Nation.” He soon got the chance to back up that boast: Captain Fetterman and his men met with some representatives of the Sioux Nation and their allies, led by Crazy Horse, on December 21, 1866, in the Powder River Basin, and the result of that battle is remembered in history books as the Fetterman Massacre—all 81 men in his party were slain. It was the Army’s worst defeat on the Plains until the Battle of Little Bighorn, 10 years later, and forced it to pull out of the area after the Fort Laramie Treaty was signed in April 1868.

More:

https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/genocide-by-other-means-us-army-slaughtered-buffalo-in-plains-indian-wars

~ ~ ~

brer cat

(24,523 posts)Destroying herds for a thrill is sick.

Duppers

(28,117 posts)Judi Lynn

(160,450 posts)to their natural home, now and forever.

May the descendants of the survivors have a real chance at life, at long, long last.

Thank you, so much, for this article.

brer cat

(24,523 posts)It is encouraging.

Demovictory9

(32,421 posts)NickB79

(19,224 posts)I was just thru South Dakota, near Rosebud, last summer. That area is REALLY impoverished. And with the drought, crops were poor everywhere.

Shooting a single bison could yield enough meat to feed a family all year. That's something.

Jilly_in_VA

(9,941 posts)I believe, belong to Ted Turner, who is extremely interested in bringing them back. As I understand it, he also employs Indigenous people to maintain and harvest them.

Roisin Ni Fiachra

(2,574 posts)stop for a large herd of buffalo who were crossing the road right in front of us. It was beautiful, and magical.

Wishing all the folks who are replenishing the buffalo herds great success.

Tommymac

(7,263 posts)hunter

(38,302 posts)For the most part this land was sustainably managed by the people who lived here in a complex manner the ignorant European immigrants didn't recognize or respect.

If we wanted to we could quit farming for fuel and industrial meat and dairy production and restore the biodiversity of this land to something resembling a natural state.