General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region Forumsclydefrand

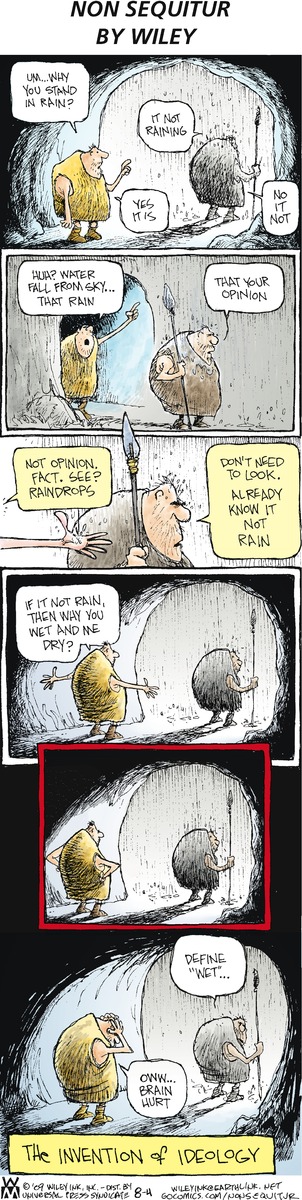

(4,325 posts)who are living in the stone age?![]()

longship

(40,416 posts)I can go with that. Reality is a bitch. The universe is what it is. I think ideologies are protections against the threats that some perceive to their world views.

Meanwhile, the mechanisms of the universe grind on.

Heidi

(58,237 posts)frazzled

(18,402 posts)and you wish to invest the time and energy, I highly recommend the book The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America (winner of the 2002 Pulitzer Prize in History), by Louis Menand. It explores the debate about ideology and belief that came in the wake of the Civil War and Darwinism and that led to the movement known as "pragmatism" in American thought. It begins by exploring the debates among Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. As a Times review states:

(...)

The young Boston Brahmin Holmes, an ardent abolitionist, fought in the Civil War, was wounded three times, lost several close friends and emerged from the experience (rendered here in dramatic, grisly detail) with a profound moral skepticism that informed all his judicial opinions. The war not only destroyed his moral beliefs, Menand writes: ''It made him lose his belief in beliefs. It impressed on his mind, in the most graphic and indelible way, a certain idea about the limits of ideas.'' To put an extremely complex set of arguments much too simply, Holmes came to see all believing as essentially betting -- since we cannot know what's right or true, we make bets, based on experience. And since people passionately hold conflicting beliefs, the only way to keep the democratic experiment going is to allow everybody to have a say. ''We do not (on Holmes's reasoning) permit the free expression of ideas because some individual may have the right one,'' Menand concludes. ''We permit free expression because we need the resources of the whole group to get the ideas we need.''

(...)

Peirce got into trouble with drugs, money, women and work. Expected to give a paper before the Metaphysical Club one night, he was said to have shown up late, then held forth on how minutes got into the habit of coming one after another. He, too, thought that all believing is betting, based on probabilistic odds, and compared it to a physician making a diagnosis: the doctor doesn't know the cause of the illness, but symptoms lead him to make an educated guess. If the remedy works, the bet becomes right. Truth happens to an idea.

Dewey, an ardent admirer of James, carried this kind of thinking into new territory at Johns Hopkins, the University of Chicago and Columbia (his writing didn't help: he wanted readers to respond to the cogency of his argument rather than the felicities of his prose and was, Menand notes, ''uncommonly successful in getting rid of the felicities''). Dewey's pragmatism found its clearest expression in the progressive school he started at Chicago, the Laboratory School, based on the idea of learning by doing: all students took carpentry, sewing and cooking -- there was a three-year course on making cereal. (My mother, who attended the Lab School in the 1920's, vividly recalls flunking French seams in the sixth grade.) Dewey thought that ideas are just tools we can use when we need them, and Menand's neat elucidation captures the deflationary dynamic of pragmatism: ''An idea has no greater metaphysical stature than, say, a fork. When your fork proves inadequate to the task of eating soup, it makes little sense to argue about whether there is something inherent in the nature of forks or something inherent in the nature of soup that accounts for the failure. You just reach for a spoon.''

http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/06/10/reviews/010610.10stroust.html

Although it can be a long read at times, it's also very lively and intriguing. I read it a decade ago but never felt I fully put everything together; I might try reading it again, because it might help me to sort out these highly ideological times!