General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region ForumsRemembering the Wounded Knee Massacre 29 december 1890)

Remembering the Wounded Knee Massacre

The Last of the Sioux

Resistant to government regulated reservations, the Sioux retreated into the Black Hills until a final massacre at Wounded Knee. On December 29, 1890, the massacre of Sioux warriors, women and children along Wounded Knee Creek in southwestern South Dakota marked the final chapter in the long war between the United States and the Native American tribes indigenous to the Great Plains.

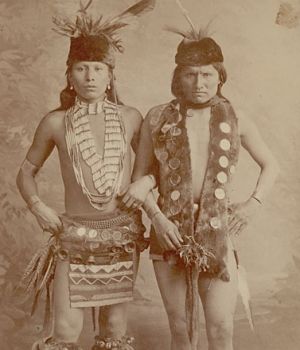

Black Elk (left) and Elk of the Ogala Lakota touring with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. (Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

For the entirety of his 27 years, Black Elk’s somber eyes had watched as the way of life for his fellow Lakota Sioux withered on the Great Plains. The medicine man had witnessed a generation of broken treaties and shattered dreams. He had watched as the white men “came in like a river” after gold was discovered in the Dakota Territory’s Black Hills in 1874, and he had been there two years later when Custer and his men were annihilated at Little Big Horn. He had seen the Lakota’s traditional hunting grounds evaporate as white men decimated the native buffalo population. The Lakota, who once roamed as free as the bison on the Great Plains, were now mostly confined to government reservations.

Life for the Sioux had become as bleak as the weather that gripped the snow-dusted prairies of South Dakota in the winter of 1890. A glimmer of hope, however, had begun to arise with the new Ghost Dance spiritual movement, which preached that Native Americans had been confined to reservations because they had angered the gods by abandoning their traditional customs. Leaders promised that the buffalo would return, relatives would be resurrected and the white man would be cast away if the Native Americans performed a ritual “ghost dance.”

As the movement began to spread, white settlers grew increasingly alarmed and feared it as a prelude to an armed uprising. “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy,” telegrammed a frightened government agent stationed on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation to the commissioner of Indian affairs on November 15, 1890. “We need protection and we need it now.” General Nelson Miles arrived on the prairie with 5,000 troops as part of the Seventh Cavalry, Custer’s old command, and ordered the arrest of several Sioux leaders.

When on December 15, 1890, Indian police tried to arrest Chief Sitting Bull, who was mistakenly believed to have been joining the Ghost Dancers, the noted Sioux leader was killed in the melee. On December 28, the cavalry caught up with Chief Big Foot, who was leading a band of upwards of 350 people to join Chief Red Cloud, near the banks of Wounded Knee Creek, which winds through the prairies and badlands of southwest South Dakota. The American forces arrested Big Foot—too ill with pneumonia to sit up, let alone walk—and positioned their Hotchkiss guns on a rise overlooking the Lakota camp.

As a bugle blared the following morning—December 29—American soldiers mounted their horses and surrounded the Native American camp. A medicine man who started to perform the ghost dance cried out, “Do not fear but let your hearts be strong. Many soldiers are about us and have many bullets, but I am assured their bullets cannot penetrate us.” He implored the heavens to scatter the soldiers like the dust he threw into the air. The cavalry, however, went teepee to teepee seizing axes, rifles and other weapons. As the soldiers attempted to confiscate a weapon they spotted under the blanket of a deaf man who could not hear their orders, a gunshot suddenly rang out. It was not clear which side shot first, but within seconds the American soldiers launched a hail of bullets from rifles, revolvers and rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns into the teepees. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Lakota offered meek resistance. Big Foot was shot where he lay on the ground. Boys who only moments before were playing leapfrog were mowed down. In just a matter of minutes, at least 150 Sioux (some historians put the number at twice as high) were killed along with 25 American soldiers. Nearly half the victims were women and children.

. . . .

http://www.history.com/news/remembering-the-wounded-knee-massacre

democrank

(11,085 posts)~PEACE~

guillaumeb

(42,641 posts)Recommended.

niyad

(113,055 posts)TexasProgresive

(12,155 posts)It is a derogatory name for the Dakota and Lakota people and should not be used.