Utah event honors Joe Hill, hero to many, murderer to others

Source: Associated Press

Utah event honors Joe Hill, hero to many, murderer to others

Brady Mccombs, Associated Press

Updated 4:57 pm, Saturday, September 5, 2015

SALT LAKE CITY (AP) — Labor activist and songwriter Joe Hill is revered by many as a hero and martyr. To others, Hill was a murderer who gunned down a Salt Lake City grocer and his son and got what he deserved when he was executed by firing squad in 1915.

. . .

"He started the struggle that we still fight today," said Dale Cox, president of the AFL-CIO in Utah. "What he worked on and what he died for is workers' rights. That's what his whole life was centered around."

. . .

Hill became the lead suspect in the 1914 double murder because he was treated by doctors the same night for a gunshot wound to the chest. Prosecutors used that as evidence linking him to the killings. Hill reportedly told doctors that he was shot by a jealous friend in a quarrel over a woman, but he didn't present that alibi at trial.

Lori Taylor, a historian and one of the organizers of Saturday's concert, said new evidence uncovered by author William Adler in a book published in 2011 cements Hill's innocence. Hill was assumed to be guilty because police of that era considered members of the Industrial Workers of the World union to be radical criminals, Taylor said. No motive was given by police.

Read more: http://www.chron.com/news/us/article/Utah-honors-Joe-Hill-hero-to-many-murderer-6487040.php

[center]

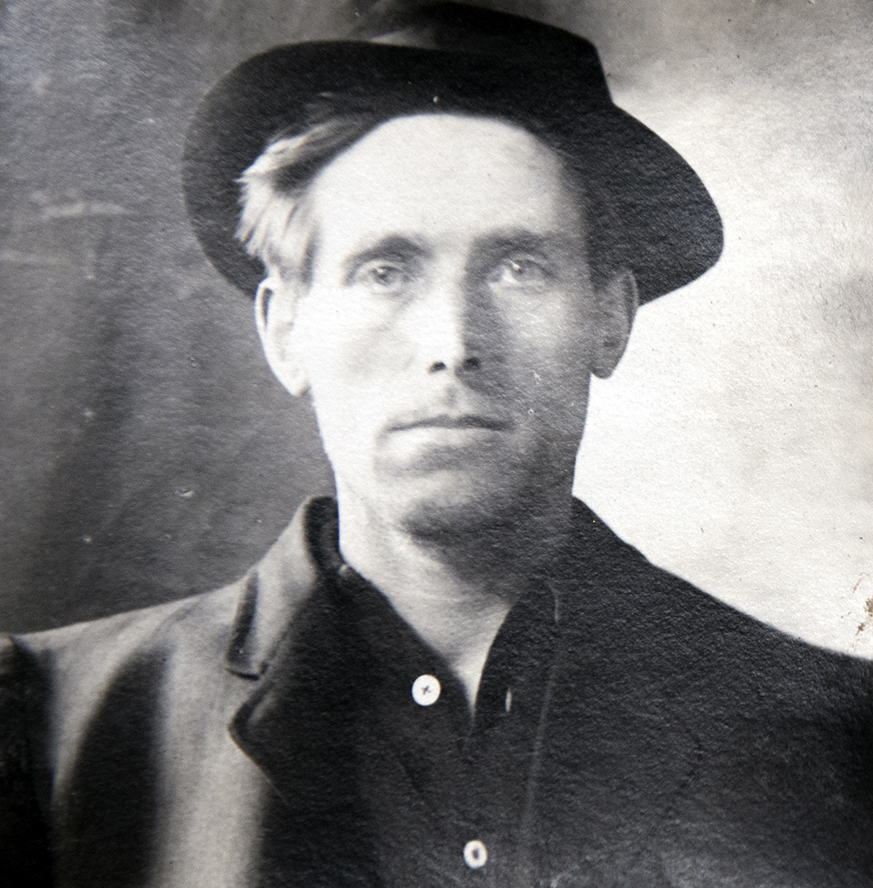

Joe Hill[/center]

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)Joe Hill (1879-1915)

A songwriter, itinerant laborer, and union organizer, Joe Hill became famous around the world after a Utah court convicted him of murder. Even before the international campaign to have his conviction reversed, however, Joe Hill was well known in hobo jungles, on picket lines and at workers' rallies as the author of popular labor songs and as an Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) agitator. Thanks in large part to his songs and to his stirring, well—publicized call to his fellow workers on the eve of his execution—"Don't waste time mourning, organize!"—Hill became, and he has remained, the best—known IWW martyr and labor folk hero.

Born Joel Hägglund on Oct. 7, 1879, the future "troubadour of discontent" grew up the fourth of six surviving children in a devoutly religious Lutheran family in Gävle, Sweden, where his father, Olaf, worked as a railroad conductor. Both his parents enjoyed music and often led the family in song. As a young man, Hill composed songs about members of his family, attended concerts at the workers' association hall in Gävle and played piano in a local café.

In 1887, Hill's father died from an occupational injury and the children were forced to quit school to support themselves. The 9-year-old Hill worked in a rope factory and later as a fireman on a steam-powered crane. Stricken with skin and joint tuberculosis in 1900, Hill moved to Stockholm in search of a cure and worked odd jobs while receiving radiation treatment and enduring a series of disfiguring operations on his face and neck. Two years later, Hill's mother, Margareta Katarina Hägglund, died after also undergoing a series of operations to cure a persistent back ailment. With her death, the six surviving Hägglund children sold the family home and ventured out on their own. Four of them settled elsewhere in Sweden, but the future Joe Hill and his younger brother, Paul, booked passage to the United States in 1902.

Little is known of Hill's doings or whereabouts for the next 12 years. He reportedly worked at various odd jobs in New York before striking out for Chicago, where he worked in a machine shop, got fired and was blacklisted for trying to organize a union. The record finds him in Cleveland in 1905, in San Francisco during the April 1906 Great Earthquake and in San Pedro, Calif., in 1910. There he joined the IWW, served for several years as the secretary for the San Pedro local and wrote many of his most famous songs, including "The Preacher and the Slave" and "Casey Jones—A Union Scab." His songs, appearing in the IWW's "Little Red Song Book," addressed the experience of vitually every major IWW group, from immigrant factory workers to homeless migratory workers to railway shopcraft workers.

More:

http://www.aflcio.org/About/Our-History/Key-People-in-Labor-History/Joe-Hill-1879-1915

Coventina

(27,094 posts)dougolat

(716 posts)...old timers about what they remembered about Joe Hill.

Quite a few were aware of the possibility of it being a convenient frame/lynching. They all remembered the coal soot during the winter hazy days.

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)1917: Frank Little of the IWW lynched

On this date in 1917, Wobbly labor organizer Frank Little was abducted from his hotel and hanged from a railroad trestle in Butte, Montana. An executive board member of the radical Industrial Workers of the World, the half-Cherokee Little had only rolled into Montana’s copper mining hub two weeks before. A roving agitator who had organized workers all around the west, he would be a signal martyr to America’s nascent Red Scare.

It was a fraught moment nationwide, and worldwide. After winning re-election on the slogan “He kept us out of war,” Woodrow Wilson upon his inauguration immediately (try to act surprised) got the United States into World War I. Just as it had in Europe, the question of war put American labor to the test: would it transfer opposition to war into resistance, or would it line up patriotically with its state?

University of Arizona’s web exhibit on the labor deportations that had expelled Frank Little from Arizona just days before he arrived in Butte) pits the militant Wobbly position against the nationalist American Federation of Labor.* And Little was one of the most stridently anti-war in his movement.

Either we’re for their capitalist slaughter fest or against it. I’m ready to face a firing squad** rather than compromise. (Source)

Anaconda Copper could nowise welcome this character’s arrival, where he would organize already-striking miners and mix in militant anti-war rhetoric with incendiary potential in the cocktail of immigrant workers being asked (in many cases) to wage war on their homelands.

The local labor conflict, an exceptionally brutal instance of a pattern across the country and especially in western mining country, was probably savage enough on its own to make Little a marked man. Whether his anti-war activity or his union activity motivated his death is not sure, but the dilemma was probably a false one for his killers just as it was for Little himself: they were two heads of the coin. As American troops poured into Europe, and particularly as the Bolshevik Revolution later in 1917 spurred a worldwide Communist scare (and a separate American military expedition), both public and private power violently pursued left-wing elements.

More:

http://www.executedtoday.com/2008/08/01/1917-frank-little-iww-lynched-butte/

[center]~ ~ ~[/center]

On edit, adding more on Frank Little, from Wikipedia:

Frank Little (unionist)

Frank H. Little (1879 – August 1, 1917) was an American labor leader who was lynched in Butte, Montana, for his union and anti-war activities. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1906, organizing miners, lumberjacks, and oil field workers. He was a member of the union's Executive Board when he was murdered.

Industrial Workers of the World

. . .

He took part in the free speech campaigns among workers in Fresno, California in 1910. Little and several hundred workers were arrested for violating a city ordinance; he was reported to have refused to work on the city rock pile. Many more IWW workers came to the city and struck in support. He also led free speech efforts in Spokane, Washington and Missoula, Montana. Little was involved in organizing lumberjacks, metal miners and oil field workers into industrial unions. On one occasion in Spokane, he was sentenced to 30 days in prison for reading the Declaration of Independence.[3] In 1910, Little successfully organized unskilled fruit workers in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

In August 1913, Little and fellow IWW organizer James P. Cannon arrived in Duluth, Minnesota, to support the strike of ore-dock workers against the Great Northern Railway over dangerous working conditions. In the course of the strike he was kidnapped, held at gunpoint outside of the city, and dramatically rescued by IWW supporters.[4]

Lynching

. . .

In the early hours of August 1, six masked men broke into Little's boardinghouse room.[1] He was beaten and taken to the edge of town where he was lynched, hanged from a railroad trestle.[1] A note with the words "First and last warning" was pinned to his thigh, referring to earlier Vigilantes giving people three warnings to stop objectionable actions.[5] The note also included the numbers 3-7-77 (a sign of Vigilantes active in the 19th century in Virginia City, Montana, some people thought referred to grave measurements), and the initials of other union leaders, suggesting they were next to be killed. The attorney for the Metal Mine Workers said after Little's murder that the union had received warnings about Joe Shannon, Tom Campbell, and another man.[1]

It was widely believed that Pinkerton agents were involved, and possibly police of Butte. No one was apprehended or prosecuted for Little's murder. An estimated 10,000 workers lined the route of his funeral procession, which was followed by 3500 more persons.[5] He was buried in Butte's Mountain View Cemetery.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Little_(unionist)

rug

(82,333 posts)Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)He appeared to have their numbers, didn't he?

So glad you posted this.

rug

(82,333 posts)retrowire

(10,345 posts)Glad to know of him! Thanks! I'll keep his memory.

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)in the U.S., like the Colombine Mine Massacre:

The Columbine Mine massacre, sometimes called the Columbine massacre, occurred in 1927, in the town of Serene, Colorado. A fight broke out between Colorado state police and a group of striking coal miners, during which the unarmed miners were attacked with machine guns. It is unclear whether the machine guns were used by the police or by guards working for the mine. Six strikers were killed, and dozens were injured.

Background[edit]

The company town of Serene, Colorado, nestled on a rolling hillside, was the home of the Columbine mine. The strike was five weeks old and strikers had been conducting morning rallies at Serene for two weeks, for the Columbine was one of the few coal mines in the state to remain in operation. On November 21, 1927, five hundred miners, some accompanied by their wives and children, arrived at the north gate just before dawn. They carried three US flags. At the direction of Josephine Roche, daughter of the recently deceased owner of Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, the picketers had been served coffee and doughnuts on previous mornings.

That morning the recently disbanded state police, also known as the Colorado Rangers, were recalled to duty and would meet them and bar their path. The miners were surprised to see men dressed in civilian clothes but armed with automatic pistols, rifles, riot guns and tear gas grenades. The Rangers were backed up by rifle-toting mine guards stationed on the mine dump. Head of the Rangers, Louis Scherf shouted to the strikers, "Who are your leaders?" "We're all leaders!" came the reply. Scherf announced the strikers would not be allowed into the town, and for a few moments they hesitated outside the fence. There was discussion, with many of the strikers asserting their right to proceed. Serene had a public post office, they argued, and some of their children were enrolled in the school in Serene. One of the Rangers was reported to have taunted, "If you want to come in here, come ahead, but we'll carry you out."

Strike leader Adam Bell stepped forward and asked that the gate be unlocked. As he put his hand on the gate one of the Rangers struck him with a club. A sixteen-year-old boy stood nearby holding one of the flags. The banner was snatched from him, and in the tug-of-war that followed the flagpole broke over the fence. The miners rushed toward the gate, and suddenly the air was filled with tear gas launched by the police. A tear gas grenade hit Mrs. Kubic in the back as she tried to get away. Some of the miners threw the tear gas grenades back.

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbine_Mine_massacre

or the Ludlow Massacre:

The Ludlow Massacre was an attack by the Colorado National Guard and Colorado Fuel & Iron Company camp guards on a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families at Ludlow, Colorado, on April 20, 1914. Some two dozen people, including miners' wives and children, were killed. The chief owner of the mine, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was widely criticized for the incident.

The massacre, the culmination of a bloody widespread strike against Colorado coal mines, resulted in the violent deaths of between 19 and 26 people; reported death tolls vary but include two women and eleven children, asphyxiated and burned to death under a single tent.[1] The deaths occurred after a daylong fight between militia and camp guards against striking workers. Ludlow was the deadliest single incident in the southern Colorado Coal Strike, which lasted from September 1913 through December 1914. The strike was organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against coal mining companies in Colorado. The three largest companies involved were the Rockefeller family-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (CF&I), the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company (RMF), and the Victor-American Fuel Company (VAF).

In retaliation for Ludlow, the miners armed themselves and attacked dozens of mines over the next ten days, destroying property and engaging in several skirmishes with the Colorado National Guard along a 40-mile front from Trinidad to Walsenburg.[2] The entire strike would cost between 69 and 199 lives. Thomas G. Andrews described it as the "deadliest strike in the history of the United States".[3]

The Ludlow Massacre was a watershed moment in American labor relations. Historian Howard Zinn described the Ludlow Massacre as "the culminating act of perhaps the most violent struggle between corporate power and laboring men in American history".[4] Congress responded to public outcry by directing the House Committee on Mines and Mining to investigate the incident.[5] Its report, published in 1915, was influential in promoting child labor laws and an eight-hour work day.

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludlow_Massacre

or the West Virginia's Mine Wars:

West Virginia's Mine Wars

Compiled by the West Virginia State Archives

On March 12, 1883, the first carload of coal was transported from Pocahontas in Tazewell County, Virginia, on the Norfolk and Western Railway. This new railroad opened a gateway to the untapped coalfields of southwestern West Virginia, precipitating a dramatic population increase. Virtually overnight, new towns were created as the region was transformed from an agricultural to industrial economy. With the lure of good wages and inexpensive housing, thousands of European immigrants rushed into southern West Virginia. In addition, a large number of African Americans migrated from the southern states. The McDowell County black population alone increased from 0.1 percent in 1880 to 30.7 percent in 1910.

Most of these new West Virginians soon became part of an economic system controlled by the coal industry. Miners worked in company mines with company tools and equipment, which they were required to lease. The rent for company housing and cost of items from the company store were deducted from their pay. The stores themselves charged over-inflated prices, since there was no alternative for purchasing goods. To ensure that miners spent their wages at the store, coal companies developed their own monetary system. Miners were paid by scrip, in the form of tokens, currency, or credit, which could be used only at the company store. Therefore, even when wages were increased, coal companies simply increased prices at the company store to balance what they lost in pay.

Miners were also denied their proper pay through a system known as cribbing. Workers were paid based on tons of coal mined. Each car brought from the mines supposedly held a specific amount of coal, such as 2,000 pounds. However, cars were altered to hold more coal than the specified amount, so miners would be paid for 2,000 pounds when they actually had brought in 2,500. In addition, workers were docked pay for slate and rock mixed in with the coal. Since docking was a judgment on the part of the checkweighman, miners were frequently cheated.

In addition to the poor economic conditions, safety in the mines was of great concern. West Virginia fell far behind other major coal-producing states in regulating mining conditions. Between 1890 and 1912, West Virginia had a higher mine death rate than any other state. West Virginia was the site of numerous deadly coal mining accidents, including the nation's worst coal disaster. On December 6, 1907, an explosion at a mine owned by the Fairmont Coal Company in Monongah, Marion County, killed 361. One historian has suggested that during World War I, a U.S. soldier had a better statistical chance of surviving in battle than did a West Virginian working in the coal mines.

More:

http://www.wvculture.org/history/minewars.html

or the Herrin Massacre in Illinois:

Illinois town honors union coal miners killed in 1922 massacre, forgotten in unmarked graves

Published June 20, 2015

Associated Press

HERRIN, Ill. – Nearly a century after literally burying its violent past, a southern Illinois community is belatedly coming to terms with one of the nation's deadliest labor conflicts, an episode in which some victims were paraded down city streets and humiliated before hundreds of cheering onlookers before having their throats slit.

Most of the victims of the Herrin Massacre — three union coal miners on strike and 20 replacement workers and guards — were buried in June 1922 in a cluster of unmarked graves in an old pauper's field at the city cemetery, forgotten by time and a collective desire to, if not ignore history, not call undue attention to it in a town that's still a union stronghold.

"No one really mentioned the massacre. It was a black eye," said retired miner Bill Sizemore, 59, who said he didn't know about it for most of his life. "The people of Herrin weren't proud of it. They all felt like it was going to wash away like the river."

But since 2009, when a local talk radio host's quest to honor a World War I veteran among the massacre victims led to an excavation of the grave site, the city started to change its approach, despite pockets of resistance. On Thursday, the anniversary of the mass burial, Herrin will unveil a monument that names 17 of the victims.

More:

http://www.foxnews.com/us/2015/06/20/illinois-town-honors-union-coal-miners-killed-in-122-massacre-forgotten-in/

or the Battle of Blair Mountain, or Matewan:

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest labor uprising in United States history and the largest organized armed uprising since the American Civil War.[1] For five days in late August and early September 1921, in Logan County, West Virginia, some 10,000 armed coal miners confronted 3,000 lawmen and strikebreakers, called the Logan Defenders,[2] who were backed by coal mine operators during an attempt by the miners to unionize the southwestern West Virginia coalfields. The battle ended after approximately one million rounds were fired,[3] and the United States Army intervened by presidential order.[4]

On May 19, 1920, 12 Baldwin-Felts agents arrived in Matewan, including Lee Felts, and promptly met up with Albert Felts who was already in the area. Albert and Lee were the brothers of Thomas Felts, the co-owner and director of the agency. Albert had already been in the area, and had tried to bribe Mayor Testerman with 500 dollars to place machine guns on roofs in the town, which Testerman refused.[5] That afternoon, Albert and Lee along with eleven other men set out to the Stone Mountain Coal Company property. The first family they evicted was a woman and her children, whose husband was not home at the time. They forced them out at gunpoint, and threw their belongings in the road under a light but steady rain. The miners who saw it were furious, and sent word to town.[6]

As the agents walked to the train station to leave town, Sid Hatfield and a group of deputized miners confronted them and told the agents they were under arrest. Albert Felts replied that in fact, he had a warrant for Sid's arrest.[7] Testerman was alerted, and he ran out into the street after a miner shouted that Sid had been arrested. Hatfield backed into the store, and Testerman asked to see the warrant. After reviewing it, the mayor exclaimed, "This is a bogus warrant." With these words, a gunfight erupted and Sid Hatfield shot Albert Felts. Mayor Testerman fell to the ground in the first volley, mortally wounded. In the end, 10 men were killed, including Albert and Lee Felts.[7] 3 of the men were from the town, the 7 others were from the agency.

This gunfight became known as the Matewan Massacre, and its symbolic significance was enormous for the miners. The seemingly invincible Baldwin-Felts had been beaten by the miners' own hero, Sid Hatfield.[8] Sid became an immediate legend and hero to the union miners, and became a symbol of hope that the oppression of coal operators and their hired guns could be overthrown.[9] Throughout the summer and into the fall of 1920, the union gained strength in Mingo County, as did the resistance of the coal operators. Low-intensity warfare was waged up and down the Tug River. In late June, state police under the command of Captain Brockus raided the Lick Creek tent colony near Williamson, West Virginia. Miners were said to have fired on Brockus and Martin's men from the colony, and in response the state police shot and arrested miners, ripped the canvas tents to shreds, and scattered the mining families' belongings.[10] Both sides were bolstering their arms, and Sid Hatfield continued to be a problem, especially when he converted Testerman's jewelry store into a gun shop.[11]

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Blair_Mountain

[font size=7]ETC.[/font]

or so many, MANY more events which actually affected so many US Americans beyond the incomprehensible treatment of the First Americans prior to the Industrial Age. We didn't get bogged down learning anything about any actual U.S. history in public schools, and you can be sure there was nothing about any of it (the truth regarding working people "problems"mentioned in the religious schools, either.

retrowire

(10,345 posts)This has been very enlightening! I LOVE reading up on history and since graduating from an education a while ago, I constantly seek new things to learn.

Speaking of history, in that last story the Battle of Blair Mountain, is that Sid Hatfield from the famous Hatfield family? As in, the Hatfield's and the McCoy's? Lonesome Dove ring a bell?

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)I couldn't wait, after seeing your post, now that there are two of us wondering about it!

Here's what I found in Wikipedia:

William Sidney "Sid" Hatfield (May 15, 1891 or 1893[1] – Aug 1, 1921), was Police Chief of Matewan, West Virginia during the Battle of Matewan, a shootout that followed a series of evictions carried out by detectives from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency.[2]

History[edit]

Hatfield was born in Blackberry, Pike County, Kentucky, the tenth of twelve children (of whom nine survived infancy) of Jacob Hatfield (c. 1843/45 – 1923), a tenant farmer, and his wife Rebecca Crabtree (b. circa 1856). His grandfather, Jeremiah Hatfield, was a half-brother to Valentine Hatfield (1789 – 1867), grandfather of William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield, leader of the Hatfield family involved in the famous Hatfield-McCoy Feud (see Hatfield Family Tree). According to the 1900 Census, two older brothers, Orison and Hereford, an older sister Chloe, and a younger sister and brother, Martha Alice and Freeland, were then still living at home with him and their parents. His eldest sister Vandalia or Vandella was already married by this time, and an older brother, Melvin, had left home.

As a child, Hatfield worked on his father's farm. He became a miner in his teens, and then worked as a blacksmith for several years. He received his nickname, "Smilin' Sid", because of the gold caps on several of his upper teeth. He seems to have had a reputation for hard living and fighting, and his appointment in 1919 to the post of Police Chief of Matewan, by the mayor, Cabell Cornelis Testerman (1882–1920), surprised some of the more 'respectable' townsfolk.[3] However, he was a staunch supporter of the United Mine Workers of America, as was Testerman: together, they were instrumental in leading the mining community's resistance to the Baldwin-Felts operatives. Operatives offered both men substantial bribes to allow them to station machine guns in the town. Hatfield and Testerman refused. The Battle of Matewan was precipitated by the Baldwin-Felts agents' attempts to evict the families of unionized miners.

On June 2, 1920, in Huntington, he married Jessie Lee Maynard (1894–1976), the widowed second wife of Testerman, who had been mortally wounded in the battle. The speed of the marriage led to an attempt at arrest and accusations by Thomas Felts and the Baldwin-Felts spy, Charles Everett Lively, that he, not Albert Felts, had shot the Mayor because of his desire for Jessie. However, according to Jessie, her first husband, aware of the danger of their situation, had asked that his friend take care of her and their young son, Jackson (1915–2001), should he be killed.[4]

The battle had given Hatfield a degree of celebrity. He appeared in a short film, Smilin' Sid, for the United Mine Workers (UMWA), and was photographed with other UMWA activists, including Mary Harris 'Mother' Jones. However, he was aware that his life was in danger from Felts, who sought vengeance for his brothers Albert and Lee. He was indicted on murder charges stemming from the Matewan shootout but was later acquitted by the jury. He was sent to stand trial with his friend and deputy, Edward Chambers, on conspiracy charges for another incident, in Welch, West Virginia. Both men arrived in Welch on August 1, 1921, unarmed and accompanied by their wives. Several Baldwin-Felts men shot them on the McDowell County Courthouse steps. Hit in the arm, and three or four times in the chest, Hatfield died instantly.[5] Chambers was shot several more times, as his wife tried to defend him, and finished off with a bullet in the head by Charles Everett Lively.[6] None of the Baldwin-Felts detectives was ever convicted of Hatfield's assassination: they claimed they had acted "in self-defense".

There was an outpouring of grief for the fallen local heroes at the funeral, which was attended by at least 3,000 people, and conducted with full honours from the Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias and Redmen (he was a member of all of these organisations).

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sid_Hatfield

Well, WELL!

Thanks for mentioning it. I would have stumbled along, wondering about it from time to time, and might never have gotten the energy channeled enough to have looked it up! This is very interesting.

Lonesome Dove was a real experience. Unique.

retrowire

(10,345 posts)Good thread for Labor Day. Thank you Judi Lynn. ![]()

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts). . . .

In the book Violence and the Labor Movement, Robert Hunter observed that workers have every reason to discourage violence, because "every time property is destroyed, or men injured, the employers win public support, the aid of the press, the pulpit, the police, the courts, and all the powers of the State. (Workers) do not knowingly injure themselves or persist in a course adverse to their material interests."[7] Yet labor-related violence has been common throughout history.

Hunter believed that violence during a strike benefits the employer, in that they are able to characterize workers negatively. Writing in 1914, Hunter stated that some employers give vague instructions to their agents to "create trouble", and that there is evidence that some employers directly instruct "incendiaries, thugs, and rioters."[8] With insurance to cover losses, Robert Hunter maintained, damage to property generally helps employers, and cannot hurt them.[9] Hunter summarized, "If the workers can be discredited and the strike broken through the aid of violence, the ordinary employer is not likely to make too rigid an investigation into whether or not his 'detectives' had a hand in it."[10]

We can identify specific examples of such circumstances, such as U.S. Senate testimony in 1936 about an employer who wanted to contract with the Pinkerton agency. Known personally to the author of the book The Pinkerton Story, this employer was characterized as a "sincerely upright and Godly man." Yet Pinkerton files record that the employer wanted the agency "to send in some thugs who could beat up the strikers."[11] In 1936, the Pinkerton agency changed its focus from strike-breaking to undercover services.[12] Pinkerton declined the request from this employer.[13]

The argument that violence benefits employers is not just theoretical, it has frequently played out in a very specific manner. For example, mine owners have used violence as an excuse to demand intervention by state police, the national guard, or even the United States army.[14][15][16] Such forces become an occupying army in a strike zone, thereby creating a protective shield for strike-breakers hired by the struck company in order to replace strikers. However, attacks on workers or their leaders could also backfire. "Rather than rendering workers docile, acts of violence frequently led to greater militancy and allegiance to [labor] leaders."[17]

Historically, violence against unions has included attacks by detective and guard agencies, such as the Pinkertons, Baldwin Felts, Burns, or Thiel detective agencies; citizens groups, such as the Citizens' Alliance; company guards; police; national guard; or even the military. In particular, there are few curbs on what detective agencies are able to get away with.[18] In the book From Blackjacks To Briefcases, Robert Michael Smith states that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, anti-union agencies spawned violence and wreaked havoc on the labor movement.[19] One investigator who participated in a congressional inquiry into industrial violence in 1916 concluded that,

Espionage is closely related to violence. Sometimes it is the direct cause of violence, and, where that cannot be charged, it is often the indirect cause. If the secret agents of employers, working as members of the labor unions, do not always investigate acts of violence, they frequently encourage them. If they did not, they would not be performing the duties for which they are paid, for they are hired on the theory that labor organizations are criminal in character.[20]

According to Morris Friedman, detective agencies were themselves for-profit companies, and a "bitter struggle" between capital and labor could be counted upon to create "satisfaction and immense profit" for agencies such as the Pinkerton company.[21] Such agencies were in the perfect position to fan suspicion and mistrust "into flames of blind and furious hatred" on the part of the companies.[22]

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-union_violence

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)An Eclectic List of Events in U.S. Labor History

- • Compiled by allen lutins (email address)

• Last Update 26 February 2013

Most citizens of the United States take for granted labor laws which protect them from the evils of unregulated industry. Perhaps the majority of those who argue for "free enterprise" and the removal of restrictions on capitalist corporations are unaware that over the course of this country's history, workers have fought and often died for protection from capitalist industry. In many instances, government troops were called out to crush strikes, at times firing on protesters. Presented below are a few of the many incidents in the (too often overlooked) tumultuous labor history of this country.

. . .

July 1835

Children employed in the silk mills in Paterson, NJ went on strike for the 11 hour day/6 day week.

1840

An Executive order issued on March 31 by President Van Buren established a 10-hour day for Federal employees on public works without reduction in pay.

1842

In the case of Commonwealth v. Hunt, the Massachusetts Court held that labor unions, as such, were legal organizations, and that "a conspiracy must be a combination of two or more persons, by some concerted action, to accomplish some criminal or unlawful purpose, or to accomplish some purpose not in itself criminal or unlawful by criminal or unlawful means." The decision also denied that an attempt to establish a closed shop was unlawful or proof of an unlawful aim.

1847

The first State law fixing 10 hours as a legal workday was passed in New Hampshire.

1848

Pennsylvania passed a State child labor law setting the minimum age for workers in commercial occupations at 12 years. In 1849, the minimum was raised to 13 years.

July 1851

Two railroad strikers were shot dead and others injured by the state militia in Portgage, New York.

1860

800 women operatives and 4,000 workmen marched during a shoemaker's strike in Lynn, Massachusetts.

1862

The "Molly Maguires," a secret society of Irish miners in the anthracite fields, first came to public attention.

1868

The first Federal 8-hour-day law was passed by Congress. It applied only to laborers, workmen, and mechanics employed by or on behalf of the United States Government.

1873

The Cigar Makers International Union made first use of the union label.

13 January 1874

The original Tompkins Square Riot. As unemployed workers demonstrated in New York's Tompkins Square Park, a detachment of mounted police charged into the crowd, beating men, women and children indiscriminately with billy clubs and leaving hundreds of casualties in their wake. Commented Abram Duryee, the Commissioner of Police: "It was the most glorious sight I ever saw..."

12 February 1877

U.S. railroad workers began strikes to protest wage cuts.

21 June 1877

Ten coal-mining activists ("Molly Maguires"

14 July 1877

A general strike halted the movement of U.S. railroads. In the following days, strike riots spread across the United States. The next week, federal troops were called out to force an end to the nationwide strike. At the "Battle of the Viaduct" in Chicago, federal troops (recently returned from an Indian massacre) killed 30 workers and wounded over 100.

1881

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU), which later became the American Federation of Labor, was organized in Pittsburgh in November with 107 delegates present. Leaders of 8 national unions attended, including Samuel Gompers, then president of the Cigar Makers International Union.

5 September 1882

Thirty thousand workers marched in the first Labor Day parade in New York City.

1884

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, forerunner of the AFL, passed a resolution stating that "8 hours shall constitute a legal day's work from and after May 1, 1886." Though the Federation did not intend to stimulate a mass insurgency, its resolution had precisely that effect.

Late 1885/Early 1886

Hundreds of thousands of American workers, increasingly determined to resist subjugation to capitalist power, poured into a fledgling labor organization, the Knights of Labor. Beginning on May 1, 1886, they took to the streets to demand the universal adoption of the eight hour day.

Chicago was the center of the movement. Workers there had been agitating for an eight hour day for months, and on the eve of May 1, 50,000 workers were already on strike. 30,000 more swelled their ranks the next day, bringing most of Chicago manufacturing to a standstill. Fears of violent class conflict gripped the city. No violence occurred on May 1 -- a Saturday -- or May 2. But on Monday, May 3, a fight involving hundreds broke out at McCormick Reaper between locked-out unionists and the non-unionist workers McCormick hired to replace them. The Chicago police, swollen in number and heavily armed, quickly moved in with clubs and guns to restore order. They left four unionists dead and many others wounded.

Angered by the deadly force of the police, a group of anarchists, led by August Spies and Albert Parsons, called on workers to arm themselves and participate in a massive protest demonstration in Haymarket Square on Tuesday evening, May 4. The demonstration appeared to be a complete bust, with only 3,000 assembling. But near the end of the evening, an individual, whose identity is still in dispute, threw a bomb that killed seven policemen and injured 67 others. Hysterical city and state government officials rounded up eight anarchists, tried them for murder, and sentenced them to death.

On 11 November 1887, four of them, including Parsons and Spies, were executed. All of the executed advocated armed struggle and violence as revolutionary methods, but their prosecutors found no evidence that any had actually thrown the Haymarket bomb. They died for their words, not their deeds. A quarter of a million people lined Chicago's street during Parson's funeral procession to express their outrage at this gross mis-carriage of justice.

For radicals and trade unionists everywhere, Haymarket became a symbol of the stark inequality and injustice of capitalist society. The May 1886 Chicago events figured prominently in the decision of the founding congress of the Second International (Paris, 1889) to make May 1, 1890 a demonstration of the solidarity and power of the international working class movement. May Day has been a celebration of international socialism and (after 1917) international communism ever since.

The Bayview Massacre also took place at this time, where seven people, including one child, were killed by state militia. On 1 May 1886 about 2,000 Polish workers walked off their jobs and gathered at Saint Stanislaus Church in Milwaukee, angrily denouncing the ten hour workday. They then marched through the city, calling on other workers to join them; as a result, all but one factory was closed down as sixteen thousand protesters gathered at Rolling Mills, prompting Wisconsin Govorner Jeremiah Rusk to call the state militia. The militia camped out at the mill while workers slept in nearby fields, and on the morning of May 5th, as protesters chanted for the eight hour workday, General Treaumer ordered his men to shoot into the crowd, some of whom were carrying sticks, bricks, and scythes, leaving seven dead at the scene. The Milwaukee Journal reported that eight more would die within twenty four hours, and without hesitation added that Governor Rusk was to be commended for his quick action in the matter.

23 November 1887

The Thibodaux Massacre. The Louisiana Militia, aided by bands of "prominent citizens," shot at least 35 unarmed black sugar workers striking to gain a dollar-per-day wage, and lynched two strike leaders.

25 July 1890

New York garment workers won the right to unionize after a seven-month strike. They secured agreements for a closed shop, and firing of all scabs.

6 July 1892

The Homestead Strike. Pinkerton Guards, trying to pave the way for the introduction of scabs, opened fire on striking Carnegie mill steel- workers in Homestead, Pennsylvania. In the ensuing battle, three Pinkertons surrendered; then, unarmed, they were set upon and beaten by a mob of townspeople, most of them women. Seven guards and eleven strikers and spectators were shot to death.

11 July 1892

Striking miners in Coeur D'Alene, Idaho dynamited the Frisco Mill, leaving it in ruins.

1893

The first of several bloody mining strikes at Cripple Creek, Colorado.

5 July 1893

During a strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company, which had drastically reduced wages, the 1892 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago's Jackson Park was set ablaze, and seven buildings were reduced to ashes. The mobs raged on, burning and looting railroad cars and fighting police in the streets, until 10 July, when 14,000 federal and state troops finally succeeded in putting down the strike.

1894

Federal troops killed 34 American Railway Union members in the Chicago area attempting to break a strike, led by Eugene Debs, against the Pullman Company. Debs and several others were imprisoned for violating injunctions, causing disintegration of the union.

21 September 1896

The state militia was sent to Leadville, Colorado to break a miner's strike.

10 September 1897

19 unarmed striking coal miners and mine workers were killed and 36 wounded by a posse organized by the Luzerne County sherif for refusing to disperse near Lattimer, Pennsylvania. The strikers, most of whom were shot in the back, were originally brought in as strike-breakers, but later organized themselves.

More:

http://www.lutins.org/labor.html

murielm99

(30,733 posts)chose to use Joe Hill as his pen name. King's son was named for the labor leader, and pays tribute to him with his choice of pen name.

Thank you for this timely and informative thread.

Judi Lynn

(160,515 posts)He has honored a very worthy person.

I'm glad to have learned this.