Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumMore thoughts on carrying capacity and sustainability

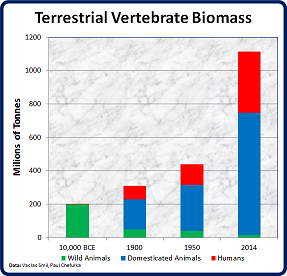

The Earth's "natural" carrying capacity for terrestrial vertebrate life is probably in the neighbourhood of 200 million tonnes. This represents the carrying capacity based on solar input only, with no assistance from human technology or fossil fuels. The estimate is derived from Vaclav Smil's biomass estimate for 1900 shown on the graph, which has been reduced by about 30% to account for technology and coal use by that time. The assumption is that by 10,000 BCE this biomass of 200 MT was fully utilizing the available solar flux.

One crucial question is what proportion of this 200 MT of biomass could be devoted to humans and their domesticated animals without excessively damaging the rest of the biosphere? This is hard to answer without a controlled experiment of course, but here's one approach.

I begin with the human population in Year 1 AD of about 250 million as a baseline. At 50 kg/person that number represents about 12.5 MT of human biomass. Domesticated animal biomass in 1900 was about three times that of humans, so that would give us an additional 37.5 MT of domesticated animals, for a total human-related biomass of 50 MT. This number represents one quarter of the estimated natural carrying capacity of the planet. That degree of appropriation is probably not completely sustainable, but would likely be OK for a few thousand years, provided there was no further human expansion beyond that number.

Because I presume that any use of technology promotes overshoot, this 250 million number also represents a human population without any significant technology beyond what was available when Christ was born.

Under this set of assumptions the planet may be overpopulated by almost 30 times.

Keep in mind that this scenario says precisely nothing about what's likely to happen in our present circumstances. In fact, the idea of voluntarily reducing our population by 97% might as well come from a different universe, it's so utterly unachievable in this one. This line of argument simply represents a way of viewing the current situation through a more ecologically holistic lens.

One additional idea to consider is that the period for which a particular population’s activity level will be sustainable is variable. The lower the collective activity level (in other words, the lower its impact on its environment) the longer the probable period of sustainability becomes.

One way I measure human impact is through what I call our “Thermodynamic Footprint”. According to this measure, modern humans have an average of 20 times the per capita impact on their environment as a hunter-gatherer. Europeans have an impact 40 times as high, while the average American impact is 80 to 100 times as high. This implies that to achieve the same period of sustainability as the 250 million humans I described above, the world could support six million average Europeans, or 2.5 million Americans.

Any increase in either population or activity levels (i.e. per-capita energy use) shortens the period of sustainability. Humans currently have an environmental impact almost 600 times as high as the baseline I proposed above - our population is 29 times higher, and our per-capita impact is 20 times higher. As a result, our period of sustainability will not be a few thousand years, but something more on the order of a small handful of decades. If we begin the countdown from the onset of heavy global industrialization around 1900, we have already burned through 11 of those "sustainable" decades.

Unfortunately, the more we look at our predicament, the more it becomes clear that no matter how we slice it or dice it, the human presence on the planet cannot be considered even remotely sustainable for much longer. And that implies that a correction in our numbers and activity levels is inevitable. The longer we proceed down the current road of technological, energetic and numerical expansion, the closer we come to that correction.

pscot

(21,024 posts)the harder the fall.

FBaggins

(26,729 posts)Do you also accept the implied corollary that technological advances do not change carrying capacity?

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)I have two definitions - the natural CC that relies just on solar flux, and the artificial CC that is produced by the technological exploitation of resource stocks or flows. When I talk about overshoot I'm usually using the former.

FBaggins

(26,729 posts)(ignoring the fluctuating path downward)... which one does the population settle at?

GliderGuider

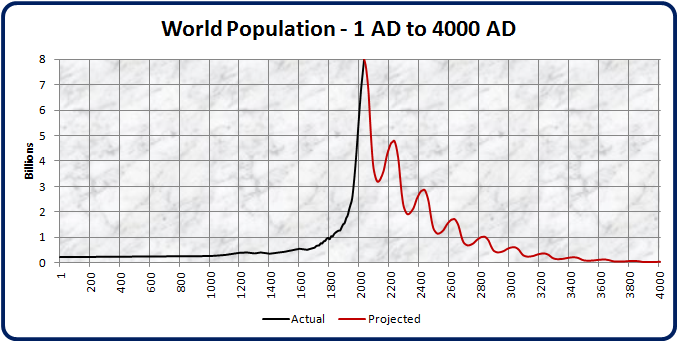

(21,088 posts)Over the long term average, by definition no population can exceed the carrying capacity. During short-term excursions it can. The question is, how long is long term? I think the "crash" could look a bit like this:

We have enough of a "technology reserve" to keep partial recoveries going for a couple of thousand years before we finally drop to the natural carrying capacity. Question is, after all that exploitation, what will the planet's natural carrying capacity be then? It could be a lot less than the 200 megatonnes of animal biomass it supported 10,000 years ago. Especially if the climate's fucked and the oceans are full of jellyfish.

FBaggins

(26,729 posts)... but that's what I was getting at when I asked about "after fluctuations".

So you don't think that technology can make a lasting difference in this supposed carrying capacity? Just add "dead cat bounces" along the way to that bottom of the curve? That is... the baseline carrying capacity is essentially a constant that population will eventually revert to.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)FBaggins

(26,729 posts)Or is it eventually just I=P?

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Energy consumption is strongly mediated by technology. If most or all all technology were to disappear, then the equation would converge on I=P. That's a mental exercise only though, because even stone hammers and fire-hardened sticks are technology. Technology won't go away so long as P>0.

NickB79

(19,233 posts)For example, upgrading the photosynthetic capabilities of various plants via genetic engineering: http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22429892.900-should-we-upgrade-photosynthesis-and-grow-supercrops.html#.VElvKRbOmoI

The enzyme in question is called RuBisCo, which catalyses the reaction that "fixes" carbon dioxide from the air to make into sugars. It is the most important enzyme in the world – almost all living things rely on it for food. But it is incredibly slow, catalysing only about three reactions per second. A typical enzyme gets through tens of thousands. It is also wasteful. RuBisCo evolved at a time when the atmosphere was rich in CO2 but devoid of oxygen. Now there's lots of oxygen and relatively little CO2, and RuBisCo has a habit of mistaking oxygen for CO2, which wastes large amounts of energy.

Its inefficiency is the main factor limiting how much of the sun's energy plants can capture. The version found in most plants has become better at identifying CO2, but at the cost of making it even slower. Meanwhile, free cyanobacteria found a way to concentrate CO2 around RuBisCo, so that they could keep the faster version.

Hence the desire to upgrade crop plants by adding cyanobacterial machinery, which could boost yields by about 25 per cent (New Scientist, 22 February 2011, p 42). What's more, such plants will need less water, because they don't need to keep their pores open as much, meaning they can better retain moisture.

Done to a wide range of species and then released into the wild, they could theoretically boost the 200 million MT biomass limit, no? A forest of GM-upgraded oaks vs a forest of unaltered oaks, perhaps? Or grasses capable of surviving on much less water, greening the American Southwest or the Sahara?

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)The question is can we maintain it at that level? Let alone keep boosting it as more people arrive and want to become more affluent?

NickB79

(19,233 posts)Whereas current CC boosting has been done via fossil fuels with a finite amount available, a deliberate release of fertile, photosynthetically boosted plants would propagate through the environment, outcompeting their native relatives, with no further human inputs required. Their descendents would be growing long after our species has turned to dust.

Of course, this is all hypothetical. If the plants did TOO well, they could just as likely create a monocrop ecosystem that could reduce rather than increase vertebrate carrying capacity via a reduction in biodiversity.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)What is this thing humans have with never being able to leave nature alone?

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)I particularly like the fluctuations where worldwide population regularly increases by 50% every 200 years, only to fall off again, to still lower levels.