Religion

Related: About this forum10 New Yorker religion articles to read while the archives are free

http://www.vox.com/2014/7/23/5926393/10-new-yorker-religion-articles-to-read-while-the-archives-are-freeUpdated by Brandon Ambrosino on July 23, 2014, 12:40 p.m. ET

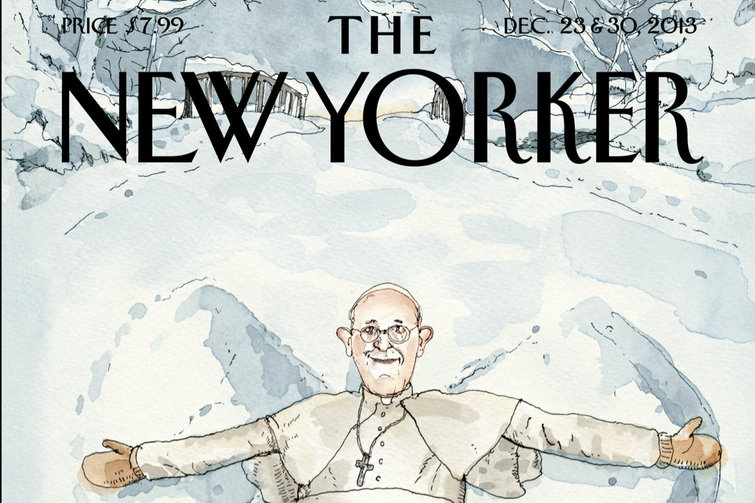

The December 23, 2013 cover of The New Yorker

The New Yorker has recently made its post-2007 archives open to the non-subscribing public for the next several months. (Some pieces published before 2007 are available, as well.) My colleague Libby Nelson put together a collection of some of the New Yorker's best education writing. I thought that was a great idea, and put together my own collection of their fantastic religion writing. My background is influenced by American evangelicalism, so the list is heavily weighted in that area; but I've included some great articles about other faith traditions, too. Here, in no particular order, is my list of ten articles you can read for free at the New Yorker.

1) The First Church of Marilynne Robinson

by Mark O'Connell

Robinson is one of my favorite contemporary writers. This essay, by Mark O'Connell, reads like an ode to Robinson's work: "When I say that I love Marilynne Robinson's work," writes O'Connell, "I'm not talking about half of it; I'm talking about every word of it." O'Connell's love of Robinson is owed both to the "grace" of her inimitable prose — for instance, "the wind that billowed her sheets announced to her the resurrection of the ordinary" — and her ability to write about religion in such a way that even he, "a more or less fully paid-up atheist," is attracted to the prose. Her work, writes O'Connell,

2) The Storyteller

by Cynthia Zarin

Another storyteller I fell in love with, but at a much younger age than Robinson, was the late Madeleine L'Engle. She was the author behind the classic A Wrinkle in Time series, for which she won a Newberry Prize, and countless essays on faith. The Storyteller is a profile on L'Engle written by Cynthia Zarin, a children's author and poet. The profile reads almost as beautifully as L'Engle's own work.

But, I asked, is there a difference between fiction and nonfiction? "Not much," she said, shrugging. It was a long shrug, the wishbone of her shoulders pulled up almost to her ears. "Because there's really no such thing as nonfiction. When people read your books, they think they know everything, but they don't. Writing is like a fairy tale. It happens elsewhere." She paused. "I had a friend, who died. She thought she could control everything. See? The story creeps up whether we want it to or not."

more at link

Brettongarcia

(2,262 posts)Last edited Thu Jul 24, 2014, 07:07 AM - Edit history (1)

What is modern, Liberal Christianity about?

Modern liberal Christianity often agrees with atheists and secularists, that to be sure, fundamentalist churches made serious mistakes. Liberal Christianity asserts that in part what was wrong with Fundamentalism, was its physical material promises of miracles and physical military triumphs. Promises that seemed to go wrong. So the solution, says modern liberal Christianity, is getting away from the old materialism of the Old Testament. In favor of spirituality instead. Reading the old promises of physical superiority as being metaphors, symbols, for mental spiritual things. Like "faith" and "love."

But there are problems in turn, we might note, even with the highest, liberal spiritual values. Like say, "love." Surprisingly, the Bible itself warned that "the heart is deceitful above all things."

Women especially like inspirational literature, liberal religion. And "love." But we can "love" the wrong things, after all. We can love illusions, and delusions, for example. And "false prophets." We can fall in love with bad things, that our deceived heart thinks are wholly good.

Among other problems? It is all too easy to give up on the material side of life, if you are born into a wealthy family. So that your material needs are taken care of. It is harder to do that, if you are born poor. Indeed, it can even be fatal, if you don't have the bare physical minimum that you need to stay physically alive and healthy.

In this sense, modern spiritual liberalism is largely the religion of, some might say, Privilege.

At best, the often excessive over-spirituality and anti-materialism of ascetic priestly spiritual liberalism, needs to be corrected. By a more secular liberalism. Which concentrates more on helping the poor not "spiritually," but in real physical material ways: minimum wage, medical care, protecting the food supply, and so forth.

Some churches do this partially, in works of "charity." And the current pope seems to be recalling the need to "help the poor." Still, none of them ever take care of the physical material side of life one tenth as well as ... Science and Technology.

Some churches give handouts. But science and technology don't just give the poor man a fish, to eat for one day; they give the poor a net. And give them the knowledge and tools ... to catch and grow their own food, every day.

Jim__

(14,063 posts)From the Mark O'Connell essay on Marilynne Robinson:

The second reason why I love Robinson, then, is how her writing puts me inside an apprehension of the world that is totally foreign to me, and that I have often approached with borderline hostility. (I’m Irish, so when I think about religion I tend to think about suffering and self-hatred. Or boredom and terror. Or the controlled intellectual and sexual famines the Catholic Church imposed on every generation of Irish people before my own. Or much worse things.) But even though I’m a more or less a fully paid-up atheist, I’m more drawn to Robinson’s Christian humanism than I am to the Dawkins-Dennett-Hitchens-Harris school of anti-theist fighting talk.

Perhaps that’s because Robinson’s moral wisdom seems inseparable from her gifts as a prose writer. Near the end of “Gilead,” Ames contemplates Jack Boughton, the wayward son of his friend Reverend Robert Boughton. He finds himself unable to understand Jack’s motivations, the reasons for the miserable and self-destructive life he has lead. “In every important way,” he writes, “we are such secrets from each other, and I do believe that there is a separate language in each of us, also a separate aesthetics and a separate jurisprudence.” Coming from a Calvinist minister, this sounds at first surprisingly like moral relativism, but what it is, really, is moral intelligence. He continues: “We take fortuitous resemblances among us to be actual likeness, because those around us have fallen heir to the same customs, trade in the same coin, acknowledge, more or less, the same notions of decency and sanity. But all that really just allows us to coexist with the inviolable, untraversable, and utterly vast spaces between us.”

This is not the kind of voice I normally associate with religious people, and it makes me wonder whether we might not be listening to the wrong voices. (A resolution: instead of clicking links to stories about the Westboro Baptist Church condemning, say, the Foo Fighters to the eternal flames of perdition, I’ll read a paragraph or two of an essay by Robinson instead.) In her new non-fiction collection, “When I Was a Child I Read Books,” there’s an essay called “Imagination and Community” in which Robinson discusses her conviction that the capacity to make imaginative connections with other people, familiar and foreign, is the basis of community:

I would say, for the moment, that community, at least community larger than the immediate family, consists very largely of imaginative love for people we do not know or whom we know very slightly. This thesis may be influenced by the fact that I have spent literal years of my life lovingly absorbed in the thoughts and perceptions of—who knows it better than I?—people who do not exist. And, just as writers are engrossed in the making of them, readers are profoundly moved and also influenced by the nonexistent, that great clan whose numbers increase prodigiously with every publishing season. I think fiction may be, whatever else, an exercise in the capacity for imaginative love, or sympathy, or identification.

This is a common enough belief, and it’s one that is frequently expressed by writers of fiction. It’s not an argument I am normally much swayed by, but Robinson’s fiction is an eloquent form of proof. She makes an atheist reader like myself capable of identifying with the sense of a fallen world that is filled with pain and sadness but also suffused with divine grace. Robinson is a Calvinist, but her spiritual sensibility is richly inclusive and non-dogmatic. There’s little talk about sin or damnation in her writing, but a lot about forgiveness and tolerance and kindness. Hers is the sort of Christianity, I suppose, that Christ could probably get behind. I’ll never share her way of seeing and thinking about the world and our place in it, but her writing has shown me the value and beauty of these perspectives.

...

cbayer

(146,218 posts)few months.

When I got the magazine, I used to savor each issue.

Brettongarcia

(2,262 posts)Last edited Fri Jul 25, 2014, 05:27 AM - Edit history (1)

Worse, a gallery full of "people who never existed," and who may be unreal, fantastic, delusory. Or "imagina"ry. Phantoms of your own mind. So that? You are really admiring not other people; but yourself. Which is not idealism, sociality; but narcissism

Even as the inner feelings that are so admired, are contradictory: 1) people have "vast and untraversable" spaces between them; but 2) this is allegedly how we build community, by traversing them.

We all need to consider this: being moved or "influenced by the nonexistent," might be dangerous: being moved by phantasms, false spirits, delusions, after all.

This author's writing is all too much like religion - and the worst aspects of it in fact. Just as she thinks she is meeting love, "community," she is really vainly locked into admiring her own mind, and subjective illusions; admiring things that do no exist. Even by her own confession.

Did you say "artistic" or "autistic"? There is a high degree of self-absorption in spirituality and estheticism. Especially one that alleges that admiring one's own sentiments leads to the deepest community. And in the moment of the self-congratulations of these authors? Pride comes before the Fall: the authors fall into vanity and narcissism, after all. And the love of things that do not exist.

The height of vanity.

For all its many virtues, there is something obviously self-admiring about religious "Humanism," of course. This is why many of us prefer the other-directedness of Science and Nature. After all.

EPILOGUE: In part the conflict here - and perhaps on DU, between say "SkepticScott" and CBayer - is also between traditional male, rational, engineering culture; with its emphasis on objective and scientific and external, empirical truth. Versus the traditional female emphasis on cooperative, internal sentiments and community; community which is pursued even at the cost of objective truth. Like in our present example possibly, the male son of the minister. Who presents the opposite: he perhaps rejects womanish religion, (in favor of reason perhaps). Even to the point of disagreeing with and being alienated from, the larger culture and its (to reason) insupportable beliefs.

To be sure, the notion of male hard science heroically disagreeing with popular superstition, flagrantly opposing popular ideas and sentimental women's culture, can be overdone as well.

So what is the solution here? Likely a reader like CBayer - a woman, but one trained in medicine, science - should be able to see both sides - and eventually work some kind of reconciliation. For many, the retreat into inspirational spirituality, is not the right, balanced answer. Possibly the answer is something like Psychology; halfway between 1) desires for communal subjective agreement, and 2) science. Or likely, I'd say, the answer consists in subjective/"spiritual" statements ... continually qualified however, by acknowledgement of cases where subjective belief is apparently contradicted by objective empirical facts.