Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Demeter

Demeter's Journal

Demeter's Journal

August 28, 2012

Demand and supply certainly matter. But there's another reason why food across the world has become so expensive: Wall Street greed... In 1991, Goldman bankers, led by their prescient president Gary Cohn, came up with a new kind of investment product, a derivative that tracked 24 raw materials, from precious metals and energy to coffee, cocoa, cattle, corn, hogs, soy, and wheat. They weighted the investment value of each element, blended and commingled the parts into sums, then reduced what had been a complicated collection of real things into a mathematical formula that could be expressed as a single manifestation, to be known henceforth as the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI). For just under a decade, the GSCI remained a relatively static investment vehicle, as bankers remained more interested in risk and collateralized debt than in anything that could be literally sowed or reaped. Then, in 1999, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission deregulated futures markets. All of a sudden, bankers could take as large a position in grains as they liked, an opportunity that had, since the Great Depression, only been available to those who actually had something to do with the production of our food.

Change was coming to the great grain exchanges of Chicago, Minneapolis, and Kansas City -- which for 150 years had helped to moderate the peaks and valleys of global food prices. Farming may seem bucolic, but it is an inherently volatile industry, subject to the vicissitudes of weather, disease, and disaster. The grain futures trading system pioneered after the American Civil War by the founders of Archer Daniels Midland, General Mills, and Pillsbury helped to establish America as a financial juggernaut to rival and eventually surpass Europe. The grain markets also insulated American farmers and millers from the inherent risks of their profession. The basic idea was the "forward contract," an agreement between sellers and buyers of wheat for a reasonable bushel price -- even before that bushel had been grown. Not only did a grain "future" help to keep the price of a loaf of bread at the bakery -- or later, the supermarket -- stable, but the market allowed farmers to hedge against lean times, and to invest in their farms and businesses. The result: Over the course of the 20th century, the real price of wheat decreased (despite a hiccup or two, particularly during the 1970s inflationary spiral), spurring the development of American agribusiness. After World War II, the United States was routinely producing a grain surplus, which became an essential element of its Cold War political, economic, and humanitarian strategies -- not to mention the fact that American grain fed millions of hungry people across the world.

Futures markets traditionally included two kinds of players. On one side were the farmers, the millers, and the warehousemen, market players who have a real, physical stake in wheat. This group not only includes corn growers in Iowa or wheat farmers in Nebraska, but major multinational corporations like Pizza Hut, Kraft, Nestlé, Sara Lee, Tyson Foods, and McDonald's -- whose New York Stock Exchange shares rise and fall on their ability to bring food to peoples' car windows, doorsteps, and supermarket shelves at competitive prices. These market participants are called "bona fide" hedgers, because they actually need to buy and sell cereals...On the other side is the speculator. The speculator neither produces nor consumes corn or soy or wheat, and wouldn't have a place to put the 20 tons of cereal he might buy at any given moment if ever it were delivered. Speculators make money through traditional market behavior, the arbitrage of buying low and selling high. And the physical stakeholders in grain futures have as a general rule welcomed traditional speculators to their market, for their endless stream of buy and sell orders gives the market its liquidity and provides bona fide hedgers a way to manage risk by allowing them to sell and buy just as they pleased. But Goldman's index perverted the symmetry of this system. The structure of the GSCI paid no heed to the centuries-old buy-sell/sell-buy patterns. This newfangled derivative product was "long only," which meant the product was constructed to buy commodities, and only buy. At the bottom of this "long-only" strategy lay an intent to transform an investment in commodities (previously the purview of specialists) into something that looked a great deal like an investment in a stock -- the kind of asset class wherein anyone could park their money and let it accrue for decades (along the lines of General Electric or Apple). Once the commodity market had been made to look more like the stock market, bankers could expect new influxes of ready cash. But the long-only strategy possessed a flaw, at least for those of us who eat. The GSCI did not include a mechanism to sell or "short" a commodity. This imbalance undermined the innate structure of the commodities markets, requiring bankers to buy and keep buying -- no matter what the price. Every time the due date of a long-only commodity index futures contract neared, bankers were required to "roll" their multi-billion dollar backlog of buy orders over into the next futures contract, two or three months down the line. And since the deflationary impact of shorting a position simply wasn't part of the GSCI, professional grain traders could make a killing by anticipating the market fluctuations these "rolls" would inevitably cause. "I make a living off the dumb money," commodity trader Emil van Essen told Businessweek last year. Commodity traders employed by the banks that had created the commodity index funds in the first place rode the tides of profit. Bankers recognized a good system when they saw it, and dozens of speculative non-physical hedgers followed Goldman's lead and joined the commodities index game, including Barclays, Deutsche Bank, Pimco, JP Morgan Chase, AIG, Bear Stearns, and Lehman Brothers, to name but a few purveyors of commodity index funds. The scene had been set for food inflation that would eventually catch unawares some of the largest milling, processing, and retailing corporations in the United States, and send shockwaves throughout the world.

The money tells the story. Since the bursting of the tech bubble in 2000, there has been a 50-fold increase in dollars invested in commodity index funds. To put the phenomenon in real terms: In 2003, the commodities futures market still totaled a sleepy $13 billion. But when the global financial crisis sent investors running scared in early 2008, and as dollars, pounds, and euros evaded investor confidence, commodities -- including food -- seemed like the last, best place for hedge, pension, and sovereign wealth funds to park their cash. "You had people who had no clue what commodities were all about suddenly buying commodities," an analyst from the United States Department of Agriculture told me. In the first 55 days of 2008, speculators poured $55 billion into commodity markets, and by July, $318 billion was roiling the markets. Food inflation has remained steady since. The money flowed, and the bankers were ready with a sparkling new casino of food derivatives. Spearheaded by oil and gas prices (the dominant commodities of the index funds) the new investment products ignited the markets of all the other indexed commodities, which led to a problem familiar to those versed in the history of tulips, dot-coms, and cheap real estate: a food bubble. Hard red spring wheat, which usually trades in the $4 to $6 dollar range per 60-pound bushel, broke all previous records as the futures contract climbed into the teens and kept on going until it topped $25. And so, from 2005 to 2008, the worldwide price of food rose 80 percent -- and has kept rising. "It's unprecedented how much investment capital we've seen in commodity markets," Kendell Keith, president of the National Grain and Feed Association, told me. "There's no question there's been speculation." In a recently published briefing note, Olivier De Schutter, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, concluded that in 2008 "a significant portion of the price spike was due to the emergence of a speculative bubble." What was happening to the grain markets was not the result of "speculation" in the traditional sense of buying low and selling high. Today, along with the cumulative index, the Standard & Poors GSCI provides 219 distinct index "tickers," so investors can boot up their Bloomberg system and bet on everything from palladium to soybean oil, biofuels to feeder cattle. But the boom in new speculative opportunities in global grain, edible oil, and livestock markets has created a vicious cycle. The more the price of food commodities increases, the more money pours into the sector, and the higher prices rise. Indeed, from 2003 to 2008, the volume of index fund speculation increased by 1,900 percent... The result of Wall Street's venture into grain and feed and livestock has been a shock to the global food production and delivery system. Not only does the world's food supply have to contend with constricted supply and increased demand for real grain, but investment bankers have engineered an artificial upward pull on the price of grain futures. The result: Imaginary wheat dominates the price of real wheat, as speculators (traditionally one-fifth of the market) now outnumber bona-fide hedgers four-to-one.

Today, bankers and traders sit at the top of the food chain -- the carnivores of the system, devouring everyone and everything below. Near the bottom toils the farmer. For him, the rising price of grain should have been a windfall, but speculation has also created spikes in everything the farmer must buy to grow his grain -- from seed to fertilizer to diesel fuel. At the very bottom lies the consumer. The average American, who spends roughly 8 to 12 percent of her weekly paycheck on food, did not immediately feel the crunch of rising costs. But for the roughly 2-billion people across the world who spend more than 50 percent of their income on food, the effects have been staggering: 250 million people joined the ranks of the hungry in 2008, bringing the total of the world's "food insecure" to a peak of 1 billion -- a number never seen before...What's the solution? The last time I visited the Minneapolis Grain Exchange, I asked a handful of wheat brokers what would happen if the U.S. government simply outlawed long-only trading in food commodities for investment banks. Their reaction: laughter. One phone call to a bona-fide hedger like Cargill or Archer Daniels Midland and one secret swap of assets, and a bank's stake in the futures market is indistinguishable from that of an international wheat buyer. What if the government outlawed all long-only derivative products, I asked? Once again, laughter. Problem solved with another phone call, this time to a trading office in London or Hong Kong; the new food derivative markets have reached supranational proportions, beyond the reach of sovereign law...

How Goldman Sachs Created the Food Crisis

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/04/27/how_goldman_sachs_created_the_food_crisis?page=fullDemand and supply certainly matter. But there's another reason why food across the world has become so expensive: Wall Street greed... In 1991, Goldman bankers, led by their prescient president Gary Cohn, came up with a new kind of investment product, a derivative that tracked 24 raw materials, from precious metals and energy to coffee, cocoa, cattle, corn, hogs, soy, and wheat. They weighted the investment value of each element, blended and commingled the parts into sums, then reduced what had been a complicated collection of real things into a mathematical formula that could be expressed as a single manifestation, to be known henceforth as the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI). For just under a decade, the GSCI remained a relatively static investment vehicle, as bankers remained more interested in risk and collateralized debt than in anything that could be literally sowed or reaped. Then, in 1999, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission deregulated futures markets. All of a sudden, bankers could take as large a position in grains as they liked, an opportunity that had, since the Great Depression, only been available to those who actually had something to do with the production of our food.

Change was coming to the great grain exchanges of Chicago, Minneapolis, and Kansas City -- which for 150 years had helped to moderate the peaks and valleys of global food prices. Farming may seem bucolic, but it is an inherently volatile industry, subject to the vicissitudes of weather, disease, and disaster. The grain futures trading system pioneered after the American Civil War by the founders of Archer Daniels Midland, General Mills, and Pillsbury helped to establish America as a financial juggernaut to rival and eventually surpass Europe. The grain markets also insulated American farmers and millers from the inherent risks of their profession. The basic idea was the "forward contract," an agreement between sellers and buyers of wheat for a reasonable bushel price -- even before that bushel had been grown. Not only did a grain "future" help to keep the price of a loaf of bread at the bakery -- or later, the supermarket -- stable, but the market allowed farmers to hedge against lean times, and to invest in their farms and businesses. The result: Over the course of the 20th century, the real price of wheat decreased (despite a hiccup or two, particularly during the 1970s inflationary spiral), spurring the development of American agribusiness. After World War II, the United States was routinely producing a grain surplus, which became an essential element of its Cold War political, economic, and humanitarian strategies -- not to mention the fact that American grain fed millions of hungry people across the world.

Futures markets traditionally included two kinds of players. On one side were the farmers, the millers, and the warehousemen, market players who have a real, physical stake in wheat. This group not only includes corn growers in Iowa or wheat farmers in Nebraska, but major multinational corporations like Pizza Hut, Kraft, Nestlé, Sara Lee, Tyson Foods, and McDonald's -- whose New York Stock Exchange shares rise and fall on their ability to bring food to peoples' car windows, doorsteps, and supermarket shelves at competitive prices. These market participants are called "bona fide" hedgers, because they actually need to buy and sell cereals...On the other side is the speculator. The speculator neither produces nor consumes corn or soy or wheat, and wouldn't have a place to put the 20 tons of cereal he might buy at any given moment if ever it were delivered. Speculators make money through traditional market behavior, the arbitrage of buying low and selling high. And the physical stakeholders in grain futures have as a general rule welcomed traditional speculators to their market, for their endless stream of buy and sell orders gives the market its liquidity and provides bona fide hedgers a way to manage risk by allowing them to sell and buy just as they pleased. But Goldman's index perverted the symmetry of this system. The structure of the GSCI paid no heed to the centuries-old buy-sell/sell-buy patterns. This newfangled derivative product was "long only," which meant the product was constructed to buy commodities, and only buy. At the bottom of this "long-only" strategy lay an intent to transform an investment in commodities (previously the purview of specialists) into something that looked a great deal like an investment in a stock -- the kind of asset class wherein anyone could park their money and let it accrue for decades (along the lines of General Electric or Apple). Once the commodity market had been made to look more like the stock market, bankers could expect new influxes of ready cash. But the long-only strategy possessed a flaw, at least for those of us who eat. The GSCI did not include a mechanism to sell or "short" a commodity. This imbalance undermined the innate structure of the commodities markets, requiring bankers to buy and keep buying -- no matter what the price. Every time the due date of a long-only commodity index futures contract neared, bankers were required to "roll" their multi-billion dollar backlog of buy orders over into the next futures contract, two or three months down the line. And since the deflationary impact of shorting a position simply wasn't part of the GSCI, professional grain traders could make a killing by anticipating the market fluctuations these "rolls" would inevitably cause. "I make a living off the dumb money," commodity trader Emil van Essen told Businessweek last year. Commodity traders employed by the banks that had created the commodity index funds in the first place rode the tides of profit. Bankers recognized a good system when they saw it, and dozens of speculative non-physical hedgers followed Goldman's lead and joined the commodities index game, including Barclays, Deutsche Bank, Pimco, JP Morgan Chase, AIG, Bear Stearns, and Lehman Brothers, to name but a few purveyors of commodity index funds. The scene had been set for food inflation that would eventually catch unawares some of the largest milling, processing, and retailing corporations in the United States, and send shockwaves throughout the world.

The money tells the story. Since the bursting of the tech bubble in 2000, there has been a 50-fold increase in dollars invested in commodity index funds. To put the phenomenon in real terms: In 2003, the commodities futures market still totaled a sleepy $13 billion. But when the global financial crisis sent investors running scared in early 2008, and as dollars, pounds, and euros evaded investor confidence, commodities -- including food -- seemed like the last, best place for hedge, pension, and sovereign wealth funds to park their cash. "You had people who had no clue what commodities were all about suddenly buying commodities," an analyst from the United States Department of Agriculture told me. In the first 55 days of 2008, speculators poured $55 billion into commodity markets, and by July, $318 billion was roiling the markets. Food inflation has remained steady since. The money flowed, and the bankers were ready with a sparkling new casino of food derivatives. Spearheaded by oil and gas prices (the dominant commodities of the index funds) the new investment products ignited the markets of all the other indexed commodities, which led to a problem familiar to those versed in the history of tulips, dot-coms, and cheap real estate: a food bubble. Hard red spring wheat, which usually trades in the $4 to $6 dollar range per 60-pound bushel, broke all previous records as the futures contract climbed into the teens and kept on going until it topped $25. And so, from 2005 to 2008, the worldwide price of food rose 80 percent -- and has kept rising. "It's unprecedented how much investment capital we've seen in commodity markets," Kendell Keith, president of the National Grain and Feed Association, told me. "There's no question there's been speculation." In a recently published briefing note, Olivier De Schutter, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, concluded that in 2008 "a significant portion of the price spike was due to the emergence of a speculative bubble." What was happening to the grain markets was not the result of "speculation" in the traditional sense of buying low and selling high. Today, along with the cumulative index, the Standard & Poors GSCI provides 219 distinct index "tickers," so investors can boot up their Bloomberg system and bet on everything from palladium to soybean oil, biofuels to feeder cattle. But the boom in new speculative opportunities in global grain, edible oil, and livestock markets has created a vicious cycle. The more the price of food commodities increases, the more money pours into the sector, and the higher prices rise. Indeed, from 2003 to 2008, the volume of index fund speculation increased by 1,900 percent... The result of Wall Street's venture into grain and feed and livestock has been a shock to the global food production and delivery system. Not only does the world's food supply have to contend with constricted supply and increased demand for real grain, but investment bankers have engineered an artificial upward pull on the price of grain futures. The result: Imaginary wheat dominates the price of real wheat, as speculators (traditionally one-fifth of the market) now outnumber bona-fide hedgers four-to-one.

Today, bankers and traders sit at the top of the food chain -- the carnivores of the system, devouring everyone and everything below. Near the bottom toils the farmer. For him, the rising price of grain should have been a windfall, but speculation has also created spikes in everything the farmer must buy to grow his grain -- from seed to fertilizer to diesel fuel. At the very bottom lies the consumer. The average American, who spends roughly 8 to 12 percent of her weekly paycheck on food, did not immediately feel the crunch of rising costs. But for the roughly 2-billion people across the world who spend more than 50 percent of their income on food, the effects have been staggering: 250 million people joined the ranks of the hungry in 2008, bringing the total of the world's "food insecure" to a peak of 1 billion -- a number never seen before...What's the solution? The last time I visited the Minneapolis Grain Exchange, I asked a handful of wheat brokers what would happen if the U.S. government simply outlawed long-only trading in food commodities for investment banks. Their reaction: laughter. One phone call to a bona-fide hedger like Cargill or Archer Daniels Midland and one secret swap of assets, and a bank's stake in the futures market is indistinguishable from that of an international wheat buyer. What if the government outlawed all long-only derivative products, I asked? Once again, laughter. Problem solved with another phone call, this time to a trading office in London or Hong Kong; the new food derivative markets have reached supranational proportions, beyond the reach of sovereign law...

August 25, 2012

Two landmark developments on August 16 give momentum to the growing interest of cities and counties in addressing the mortgage mess using eminent domain:

MERS is the electronic smokescreen that allowed banks to build their securitization Ponzi scheme without worrying about details like ownership and chain of title. According to property law attorney Neil Garfield, properties were sold to multiple investors or conveyed to empty trusts, subprime securities were endorsed as triple A and banks earned up to 40 times what they could earn on a paying loan, using credit default swaps in which they bet the loan would go into default. As the dust settles from the collapse of the scheme, homeowners are left with underwater mortgages with no legitimate owners to negotiate with. The solution now being considered is for municipalities to simply take ownership of the mortgages through eminent domain. This would allow them to clear title and start fresh, along with some other lucrative dividends.

A major snag in these proposals has been that to make them economically feasible, the mortgages would have to be purchased at less than fair market value, in violation of eminent domain laws. But for troubled properties with MERS in the title - which now seems to be the majority of them - this may no longer be a problem. If MERS is not a beneficiary entitled to foreclose, as held in Bain, it is not entitled to assign that right or to assign title. Title remains with the original note holder; and in the typical case, the note holder can no longer be located or established, since the property has been used as collateral for multiple investors. In these cases, counties or cities may be able to obtain the mortgages free and clear. The county or city would then be in a position to "do the fair thing," settling with stakeholders in proportion to their legitimate claims and refinancing or reselling the properties, with proceeds accruing to the city or county.

Bain v. MERS: No Rights Without the Original Note

The underlying question, said the Bain panel, was "whether MERS and its associated business partners and institutions can both replace the existing recording system established by Washington statutes and still take advantage of legal procedures established in those same statutes." The court held that they could not have it both ways:

Bain is binding precedent only in Washington State, but it is well reasoned and is expected to be followed elsewhere.

READ ON...IT GETS BETTER!

Real Remedies for the Foreclosure Crisis Exist: The Game-Changing Implications of Bain v. MERS

http://truth-out.org/news/item/11045-real-remedies-for-the-foreclosure-crisis-exist-the-game-changing-implications-of-bain-v-mersTwo landmark developments on August 16 give momentum to the growing interest of cities and counties in addressing the mortgage mess using eminent domain:

- The Washington State Supreme Court held in Bain v. MERS, et al., that an electronic database called Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems (MERS) is not a "beneficiary" entitled to foreclose under a deed of trust; and

- San Bernardino County, California, passed a resolution to consider plans to use eminent domain to address the glut of underwater borrowers by purchasing and refinancing their loans.

MERS is the electronic smokescreen that allowed banks to build their securitization Ponzi scheme without worrying about details like ownership and chain of title. According to property law attorney Neil Garfield, properties were sold to multiple investors or conveyed to empty trusts, subprime securities were endorsed as triple A and banks earned up to 40 times what they could earn on a paying loan, using credit default swaps in which they bet the loan would go into default. As the dust settles from the collapse of the scheme, homeowners are left with underwater mortgages with no legitimate owners to negotiate with. The solution now being considered is for municipalities to simply take ownership of the mortgages through eminent domain. This would allow them to clear title and start fresh, along with some other lucrative dividends.

A major snag in these proposals has been that to make them economically feasible, the mortgages would have to be purchased at less than fair market value, in violation of eminent domain laws. But for troubled properties with MERS in the title - which now seems to be the majority of them - this may no longer be a problem. If MERS is not a beneficiary entitled to foreclose, as held in Bain, it is not entitled to assign that right or to assign title. Title remains with the original note holder; and in the typical case, the note holder can no longer be located or established, since the property has been used as collateral for multiple investors. In these cases, counties or cities may be able to obtain the mortgages free and clear. The county or city would then be in a position to "do the fair thing," settling with stakeholders in proportion to their legitimate claims and refinancing or reselling the properties, with proceeds accruing to the city or county.

Bain v. MERS: No Rights Without the Original Note

The underlying question, said the Bain panel, was "whether MERS and its associated business partners and institutions can both replace the existing recording system established by Washington statutes and still take advantage of legal procedures established in those same statutes." The court held that they could not have it both ways:

Simply put, if MERS does not hold the note, it is not a lawful beneficiary....

MERS suggests that, if we find a violation of the act, "MERS should be required to assign its interest in any deed of trust to the holder of the promissory note and have that assignment recorded in the land title records, before any non-judicial foreclosure could take place." But if MERS is not the beneficiary as contemplated by Washington law, it is unclear what rights, if any, it has to convey. Other courts have rejected similar suggestions. [Citations omitted.]

MERS suggests that, if we find a violation of the act, "MERS should be required to assign its interest in any deed of trust to the holder of the promissory note and have that assignment recorded in the land title records, before any non-judicial foreclosure could take place." But if MERS is not the beneficiary as contemplated by Washington law, it is unclear what rights, if any, it has to convey. Other courts have rejected similar suggestions. [Citations omitted.]

Bain is binding precedent only in Washington State, but it is well reasoned and is expected to be followed elsewhere.

READ ON...IT GETS BETTER!

August 24, 2012

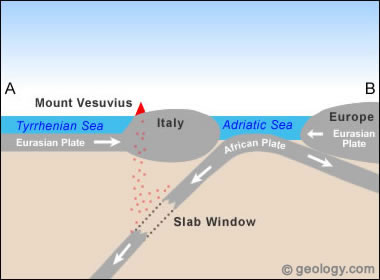

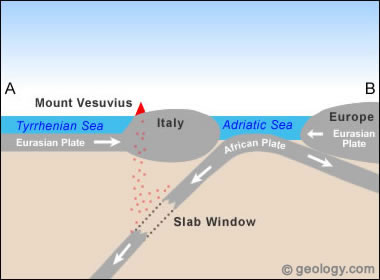

In AD 79 on this date...

After centuries of dormancy, Mount Vesuvius erupts in southern Italy, devastating the prosperous Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and killing thousands. The cities, buried under a thick layer of volcanic material and mud, were never rebuilt and largely forgotten in the course of history. In the 18th century, Pompeii and Herculaneum were rediscovered and excavated, providing an unprecedented archaeological record of the everyday life of an ancient civilization, startlingly preserved in sudden death.

The ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum thrived near the base of Mount Vesuvius at the Bay of Naples. In the time of the early Roman Empire, 20,000 people lived in Pompeii, including merchants, manufacturers, and farmers who exploited the rich soil of the region with numerous vineyards and orchards. None suspected that the black fertile earth was the legacy of earlier eruptions of Mount Vesuvius. Herculaneum was a city of 5,000 and a favorite summer destination for rich Romans. Named for the mythic hero Hercules, Herculaneum housed opulent villas and grand Roman baths. Gambling artifacts found in Herculaneum and a brothel unearthed in Pompeii attest to the decadent nature of the cities. There were smaller resort communities in the area as well, such as the quiet little town of Stabiae.

At noon on August 24, 79 A.D., this pleasure and prosperity came to an end when the peak of Mount Vesuvius exploded, propelling a 10-mile mushroom cloud of ash and pumice into the stratosphere. For the next 12 hours, volcanic ash and a hail of pumice stones up to 3 inches in diameter showered Pompeii, forcing the city's occupants to flee in terror. Some 2,000 people stayed in Pompeii, holed up in cellars or stone structures, hoping to wait out the eruption.

A westerly wind protected Herculaneum from the initial stage of the eruption, but then a giant cloud of hot ash and gas surged down the western flank of Vesuvius, engulfing the city and burning or asphyxiating all who remained. This lethal cloud was followed by a flood of volcanic mud and rock, burying the city.

The people who remained in Pompeii were killed on the morning of August 25 when a cloud of toxic gas poured into the city, suffocating all that remained. A flow of rock and ash followed, collapsing roofs and walls and burying the dead.

Much of what we know about the eruption comes from an account by Pliny the Younger, who was staying west along the Bay of Naples when Vesuvius exploded. In two letters to the historian Tacitus, he told of how "people covered their heads with pillows, the only defense against a shower of stones," and of how "a dark and horrible cloud charged with combustible matter suddenly broke and set forth. Some bewailed their own fate. Others prayed to die." Pliny, only 17 at the time, escaped the catastrophe and later became a noted Roman writer and administrator. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, was less lucky. Pliny the Elder, a celebrated naturalist, at the time of the eruption was the commander of the Roman fleet in the Bay of Naples. After Vesuvius exploded, he took his boats across the bay to Stabiae, to investigate the eruption and reassure terrified citizens. After going ashore, he was overcome by toxic gas and died.

According to Pliny the Younger's account, the eruption lasted 18 hours. Pompeii was buried under 14 to 17 feet of ash and pumice, and the nearby seacoast was drastically changed. Herculaneum was buried under more than 60 feet of mud and volcanic material. Some residents of Pompeii later returned to dig out their destroyed homes and salvage their valuables, but many treasures were left and then forgotten.

In the 18th century, a well digger unearthed a marble statue on the site of Herculaneum. The local government excavated some other valuable art objects, but the project was abandoned. In 1748, a farmer found traces of Pompeii beneath his vineyard. Since then, excavations have gone on nearly without interruption until the present. In 1927, the Italian government resumed the excavation of Herculaneum, retrieving numerous art treasures, including bronze and marble statues and paintings.

The remains of 2,000 men, women, and children were found at Pompeii. After perishing from asphyxiation, their bodies were covered with ash that hardened and preserved the outline of their bodies. Later, their bodies decomposed to skeletal remains, leaving a kind of plaster mold behind. Archaeologists who found these molds filled the hollows with plaster, revealing in grim detail the death pose of the victims of Vesuvius. The rest of the city is likewise frozen in time, and ordinary objects that tell the story of everyday life in Pompeii are as valuable to archaeologists as the great unearthed statues and frescoes. It was not until 1982 that the first human remains were found at Herculaneum, and these hundreds of skeletons bear ghastly burn marks that testifies to horrifying deaths.

Today, Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano on the European mainland. Its last eruption was in 1944 and its last major eruption was in 1631. Another eruption is expected in the near future, would could be devastating for the 700,000 people who live in the "death zones" around Vesuvius.

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history

It all looks peaceful and calm. Oh, sometimes there's a little rumbling, a burst of steam, or even a shower of ash. But we're just going about our lives, just like the citizens of Pompeii and Herculaneum did. Until the volcano of financial fraud and abuse blows the top off the global economy.

Then we will see who lives, who dies, and who gets to tell the tale...

Post your rumbles and seismic data below.

Weekend Economists Go Out with a Boom August 24-26, 2012

In AD 79 on this date...

After centuries of dormancy, Mount Vesuvius erupts in southern Italy, devastating the prosperous Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and killing thousands. The cities, buried under a thick layer of volcanic material and mud, were never rebuilt and largely forgotten in the course of history. In the 18th century, Pompeii and Herculaneum were rediscovered and excavated, providing an unprecedented archaeological record of the everyday life of an ancient civilization, startlingly preserved in sudden death.

The ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum thrived near the base of Mount Vesuvius at the Bay of Naples. In the time of the early Roman Empire, 20,000 people lived in Pompeii, including merchants, manufacturers, and farmers who exploited the rich soil of the region with numerous vineyards and orchards. None suspected that the black fertile earth was the legacy of earlier eruptions of Mount Vesuvius. Herculaneum was a city of 5,000 and a favorite summer destination for rich Romans. Named for the mythic hero Hercules, Herculaneum housed opulent villas and grand Roman baths. Gambling artifacts found in Herculaneum and a brothel unearthed in Pompeii attest to the decadent nature of the cities. There were smaller resort communities in the area as well, such as the quiet little town of Stabiae.

At noon on August 24, 79 A.D., this pleasure and prosperity came to an end when the peak of Mount Vesuvius exploded, propelling a 10-mile mushroom cloud of ash and pumice into the stratosphere. For the next 12 hours, volcanic ash and a hail of pumice stones up to 3 inches in diameter showered Pompeii, forcing the city's occupants to flee in terror. Some 2,000 people stayed in Pompeii, holed up in cellars or stone structures, hoping to wait out the eruption.

A westerly wind protected Herculaneum from the initial stage of the eruption, but then a giant cloud of hot ash and gas surged down the western flank of Vesuvius, engulfing the city and burning or asphyxiating all who remained. This lethal cloud was followed by a flood of volcanic mud and rock, burying the city.

The people who remained in Pompeii were killed on the morning of August 25 when a cloud of toxic gas poured into the city, suffocating all that remained. A flow of rock and ash followed, collapsing roofs and walls and burying the dead.

Much of what we know about the eruption comes from an account by Pliny the Younger, who was staying west along the Bay of Naples when Vesuvius exploded. In two letters to the historian Tacitus, he told of how "people covered their heads with pillows, the only defense against a shower of stones," and of how "a dark and horrible cloud charged with combustible matter suddenly broke and set forth. Some bewailed their own fate. Others prayed to die." Pliny, only 17 at the time, escaped the catastrophe and later became a noted Roman writer and administrator. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, was less lucky. Pliny the Elder, a celebrated naturalist, at the time of the eruption was the commander of the Roman fleet in the Bay of Naples. After Vesuvius exploded, he took his boats across the bay to Stabiae, to investigate the eruption and reassure terrified citizens. After going ashore, he was overcome by toxic gas and died.

According to Pliny the Younger's account, the eruption lasted 18 hours. Pompeii was buried under 14 to 17 feet of ash and pumice, and the nearby seacoast was drastically changed. Herculaneum was buried under more than 60 feet of mud and volcanic material. Some residents of Pompeii later returned to dig out their destroyed homes and salvage their valuables, but many treasures were left and then forgotten.

In the 18th century, a well digger unearthed a marble statue on the site of Herculaneum. The local government excavated some other valuable art objects, but the project was abandoned. In 1748, a farmer found traces of Pompeii beneath his vineyard. Since then, excavations have gone on nearly without interruption until the present. In 1927, the Italian government resumed the excavation of Herculaneum, retrieving numerous art treasures, including bronze and marble statues and paintings.

The remains of 2,000 men, women, and children were found at Pompeii. After perishing from asphyxiation, their bodies were covered with ash that hardened and preserved the outline of their bodies. Later, their bodies decomposed to skeletal remains, leaving a kind of plaster mold behind. Archaeologists who found these molds filled the hollows with plaster, revealing in grim detail the death pose of the victims of Vesuvius. The rest of the city is likewise frozen in time, and ordinary objects that tell the story of everyday life in Pompeii are as valuable to archaeologists as the great unearthed statues and frescoes. It was not until 1982 that the first human remains were found at Herculaneum, and these hundreds of skeletons bear ghastly burn marks that testifies to horrifying deaths.

Today, Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano on the European mainland. Its last eruption was in 1944 and its last major eruption was in 1631. Another eruption is expected in the near future, would could be devastating for the 700,000 people who live in the "death zones" around Vesuvius.

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history

It all looks peaceful and calm. Oh, sometimes there's a little rumbling, a burst of steam, or even a shower of ash. But we're just going about our lives, just like the citizens of Pompeii and Herculaneum did. Until the volcano of financial fraud and abuse blows the top off the global economy.

Then we will see who lives, who dies, and who gets to tell the tale...

Post your rumbles and seismic data below.

August 24, 2012

Yves here. I’m featuring this post not simply because the student debt issue is coming to serve as a form of debt servitude, but also because the backstory is so ugly. Student debt is the only form of consumer lending where the obligation cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. This story chronicles how persistent bank lobbying, including disinformation portraying student borrowers as likely deadbeats, led to increasingly draconian treatment of student loans. A second reason for posting it is that due to technical difficulties at Reuters, the original ran without the hyperlinks, which are of interest to serious readers.

*********************************************************

Lobbyists' trillion dollar revenge on nerds

You have probably mentally catalogued the student loan crisis alongside all the other looming trillion dollar crises busy imperiling civilization for the purpose of enriching the already rich. But it is different from those crises in a few significant ways, starting with the fact that the entire student loan business is arguably unconstitutional. You don’t have to take it from me: a preeminent bankruptcy scholar made precisely this argument under oath before Congress. In December 1975, when Congress was debating the first law that made student loans non-dischargeable in bankruptcy, University of Connecticut law professor Philip Shuchman testified that students “should not be singled out for special and discriminatory treatment,” adding that the idea gave him “the further very literal feeling that this is almost a denial of their right to equal protection of the laws.”

The thing was, discrimination was kinda the whole idea. Stagflation was sending an unprecedented number of Silent Majority members into bankruptcy, and the bank lobby was fighting back with a propaganda assault that scapegoated counterculture student delinquents who were allegedly taking loans with no goal of paying them. As Shuchman and others explained in hearings, only about 4% of people who filed for bankruptcy protection in 1975 had student loans on their balance sheets, and of those fewer than one fifth did not have substantial other debts motivating them to file.

But try telling that to anyone who'd been reading the papers! A typical syndicated dispatch on the surge in student deadbeats was the August 27, 1972 expose of Los Angeles Times reporter Linda Mathews, which began with the personal anecdote of an anonymous “Washington banker” who purported to have once “handed a $1500 check” for the year’s tuition to a nameless “18-year-old college freshman” only to be insouciantly told, “Oh, I never intend to repay this loan.” The kid was merely acting on the advice of “underground newspapers,” the anonymous banker—who had since joined “the staff of the American Banking (sic) Association”—helpfully explained. “Elitist cheaters” and “professional deadbeats” had driven default rates “as high as 40 percent in some cases,” the Chicago Tribune fumed. “Sometimes when I see someone come out before me with a job and no other debt but a college loan—and not even a big one at that—I feel like saying, 'Why you little stinker,'” a judge told the New York Times. A Wall Street Journal editorial on “the educational subculture” blamed the “crisis” on “an attitude of unconcern—that default really isn't like ripping off anybody, just the large, impersonal government that wastes plenty of money on other things” that was apparently pervasive throughout the entire education profession.

But to the credit of the American legislature of the day, the majority of its members were still capable of distinguishing between PR and reality. It concluded its round of hearings in February 1976 bypostponing the vote on the non-dischargeability amendment pending a formal Government Accounting Office study on the matter, which in turn confirmed earlier findings that deliberate student deadbeats comprised a virtually infinitesimal proportion of bankruptcies. In the meantime, mainstream journalists who spent more time in reality than their trend-setting contemporaries uncovered some troubling (and real) trends while scouring bankruptcy filings. Of the small population of twentysomethings who did seek to use bankruptcy protection primarily to discharge student loans, many had been defrauded by fly-by-night "correspondence schools” that had forged the students’ signatures and saddled them with staggering loans. They hadn't even known about them until they started getting hounded by collection agencies. By 1977 even the American Bankers Association had joined the conference of bankruptcy judges in lobbying—formally, anyway—against the cruel and unusual punishment of making student debt non-dischargeable. As James O’Hara, the congressman who had commissioned the GAO study, pointed out in his testimony, to enact such a law would be tantamount to “treating students, all students, as though they were suspected frauds and felons” while according arbitrary second-class creditor status to “the grocery store, the tailor or the doctor to whom the same student may also owe money.” In 1978 the House of Representatives voted to pass a bankruptcy reform bill that specifically restored student loans to their original status as equivalent to any other form of unsecured debt...But then the bill went to conference committee with the Senate, and the clause came back. Like the loans themselves, it could not be gotten rid of. At first this provision applied only during the first five years of the life of the loan; then it was seven, then eternity. Until 2005 it only applied to federally guaranteed loans; now it applies to all.

MORE AT LINK

THIS IS TRULY HORRIFIC, AND IT JUST GETS WORSE...MUST READ AND SEND TO ALL POTENTIAL COLLEGE STUDENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES

Moe Tkacik: Student Debt – The Unconstitutional 40 Year War on Students

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/08/moe-tkacik-student-debt-the-unconstitutional-40-year-war-on-students.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+NakedCapitalism+%28naked+capitalism%29Yves here. I’m featuring this post not simply because the student debt issue is coming to serve as a form of debt servitude, but also because the backstory is so ugly. Student debt is the only form of consumer lending where the obligation cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. This story chronicles how persistent bank lobbying, including disinformation portraying student borrowers as likely deadbeats, led to increasingly draconian treatment of student loans. A second reason for posting it is that due to technical difficulties at Reuters, the original ran without the hyperlinks, which are of interest to serious readers.

*********************************************************

Lobbyists' trillion dollar revenge on nerds

You have probably mentally catalogued the student loan crisis alongside all the other looming trillion dollar crises busy imperiling civilization for the purpose of enriching the already rich. But it is different from those crises in a few significant ways, starting with the fact that the entire student loan business is arguably unconstitutional. You don’t have to take it from me: a preeminent bankruptcy scholar made precisely this argument under oath before Congress. In December 1975, when Congress was debating the first law that made student loans non-dischargeable in bankruptcy, University of Connecticut law professor Philip Shuchman testified that students “should not be singled out for special and discriminatory treatment,” adding that the idea gave him “the further very literal feeling that this is almost a denial of their right to equal protection of the laws.”

The thing was, discrimination was kinda the whole idea. Stagflation was sending an unprecedented number of Silent Majority members into bankruptcy, and the bank lobby was fighting back with a propaganda assault that scapegoated counterculture student delinquents who were allegedly taking loans with no goal of paying them. As Shuchman and others explained in hearings, only about 4% of people who filed for bankruptcy protection in 1975 had student loans on their balance sheets, and of those fewer than one fifth did not have substantial other debts motivating them to file.

But try telling that to anyone who'd been reading the papers! A typical syndicated dispatch on the surge in student deadbeats was the August 27, 1972 expose of Los Angeles Times reporter Linda Mathews, which began with the personal anecdote of an anonymous “Washington banker” who purported to have once “handed a $1500 check” for the year’s tuition to a nameless “18-year-old college freshman” only to be insouciantly told, “Oh, I never intend to repay this loan.” The kid was merely acting on the advice of “underground newspapers,” the anonymous banker—who had since joined “the staff of the American Banking (sic) Association”—helpfully explained. “Elitist cheaters” and “professional deadbeats” had driven default rates “as high as 40 percent in some cases,” the Chicago Tribune fumed. “Sometimes when I see someone come out before me with a job and no other debt but a college loan—and not even a big one at that—I feel like saying, 'Why you little stinker,'” a judge told the New York Times. A Wall Street Journal editorial on “the educational subculture” blamed the “crisis” on “an attitude of unconcern—that default really isn't like ripping off anybody, just the large, impersonal government that wastes plenty of money on other things” that was apparently pervasive throughout the entire education profession.

But to the credit of the American legislature of the day, the majority of its members were still capable of distinguishing between PR and reality. It concluded its round of hearings in February 1976 bypostponing the vote on the non-dischargeability amendment pending a formal Government Accounting Office study on the matter, which in turn confirmed earlier findings that deliberate student deadbeats comprised a virtually infinitesimal proportion of bankruptcies. In the meantime, mainstream journalists who spent more time in reality than their trend-setting contemporaries uncovered some troubling (and real) trends while scouring bankruptcy filings. Of the small population of twentysomethings who did seek to use bankruptcy protection primarily to discharge student loans, many had been defrauded by fly-by-night "correspondence schools” that had forged the students’ signatures and saddled them with staggering loans. They hadn't even known about them until they started getting hounded by collection agencies. By 1977 even the American Bankers Association had joined the conference of bankruptcy judges in lobbying—formally, anyway—against the cruel and unusual punishment of making student debt non-dischargeable. As James O’Hara, the congressman who had commissioned the GAO study, pointed out in his testimony, to enact such a law would be tantamount to “treating students, all students, as though they were suspected frauds and felons” while according arbitrary second-class creditor status to “the grocery store, the tailor or the doctor to whom the same student may also owe money.” In 1978 the House of Representatives voted to pass a bankruptcy reform bill that specifically restored student loans to their original status as equivalent to any other form of unsecured debt...But then the bill went to conference committee with the Senate, and the clause came back. Like the loans themselves, it could not be gotten rid of. At first this provision applied only during the first five years of the life of the loan; then it was seven, then eternity. Until 2005 it only applied to federally guaranteed loans; now it applies to all.

MORE AT LINK

THIS IS TRULY HORRIFIC, AND IT JUST GETS WORSE...MUST READ AND SEND TO ALL POTENTIAL COLLEGE STUDENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES

August 22, 2012

A Michigan State Police detective said he believed House Speaker Jase Bolger and state Rep. Roy Schmidt may have conspired to commit perjury when they recruited a fake Democratic candidate to run for a Grand Rapids House seat, records obtained by the Free Press show.

Detective Sgt. Robert Davis swore in an affidavit for obtaining search warrants that Bolger and Schmidt may have committed the crime if they helped 22-year-old Matt Mojzak file his affidavit of candidacy knowing that his residency information was false, according to records obtained under Michigan's Freedom of Information Act.

Kent County Prosecutor William Forsyth shut down the investigation before Davis was able to execute three search warrants that a judge approved -- including one for the cell phone records of Bolger, R-Marshall.

Forsyth, a Republican, said he didn't believe continuing the investigation was fruitful because he concluded no crime had been committed....

MORE

Detective believes Bolger, Schmidt conspired to commit perjury in state House scandal

http://www.freep.com/article/20120820/NEWS01/308200034A Michigan State Police detective said he believed House Speaker Jase Bolger and state Rep. Roy Schmidt may have conspired to commit perjury when they recruited a fake Democratic candidate to run for a Grand Rapids House seat, records obtained by the Free Press show.

Detective Sgt. Robert Davis swore in an affidavit for obtaining search warrants that Bolger and Schmidt may have committed the crime if they helped 22-year-old Matt Mojzak file his affidavit of candidacy knowing that his residency information was false, according to records obtained under Michigan's Freedom of Information Act.

Kent County Prosecutor William Forsyth shut down the investigation before Davis was able to execute three search warrants that a judge approved -- including one for the cell phone records of Bolger, R-Marshall.

Forsyth, a Republican, said he didn't believe continuing the investigation was fruitful because he concluded no crime had been committed....

MORE

August 22, 2012

Ponzi growth happens when unsustainable capital flows, wilfully predicated upon funding schemes that Reason knows to be fraudulent, give rise to large spurts of economic activity.

Ponzi austerity, in contrast, is what happens when unsustainable spending cuts, wilfully predicated upon funding schemes that Reason knows to be fraudulent, cause significant drops in economic activity. (Click here for my original piece on Ponzi Growth and how it led to Ponzi Austerity.)

It is an incontestable fact that Europe’s Periphery shifted from Ponzi growth to Ponzi austerity some time after the Crash of 2008. Before the Crash, tsunamis of toxic money, minted and multiplied by US, UK and German banks, flooded the Periphery, causing bubbles in the real estate and public sectors. When that toxic money fizzled out, and capital receded from the Periphery like a vicious tide going out on a grim shore, the Periphery’s states and banks sunk deeply in the mud of irreversible insolvency. So as to delay the inevitable defaults that would strike huge blows on the tittering northern banks, so-called bailouts were arranged on condition of austerity policies that were as unsustainable as the growth whose collapse led to them.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the only serious institution that the Eurozone has. It was meant to be the guardian of the euro’s credibility but, alas, during both periods (Ponzi growth and Ponzi austerity), the ECB proved incapable of playing this role. When toxic capital flowed disastrously into the Periphery, the ECB whistled in the wind. When it flowed out, causing the collapse that then gave rise to the Ponzi austerity, the ECB was part and parcel of this crime against the peoples and the spirit of Europe. Now that the chickens are coming home to roost, the ECB is pledging to do “all it takes” to save the euro, but fails to back up such strong words with deeds...

MORE AT LINK---EXPLAINS A LOT ABOUT THE EUROZONE MADNESS

PONZI AUSTERITY (I didn't like the original title)

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/08/yanis-varoufakis-how-the-ecb-is-complicit-in-a-macro-financial-debacle.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+NakedCapitalism+%28naked+capitalism%29Ponzi growth happens when unsustainable capital flows, wilfully predicated upon funding schemes that Reason knows to be fraudulent, give rise to large spurts of economic activity.

Ponzi austerity, in contrast, is what happens when unsustainable spending cuts, wilfully predicated upon funding schemes that Reason knows to be fraudulent, cause significant drops in economic activity. (Click here for my original piece on Ponzi Growth and how it led to Ponzi Austerity.)

It is an incontestable fact that Europe’s Periphery shifted from Ponzi growth to Ponzi austerity some time after the Crash of 2008. Before the Crash, tsunamis of toxic money, minted and multiplied by US, UK and German banks, flooded the Periphery, causing bubbles in the real estate and public sectors. When that toxic money fizzled out, and capital receded from the Periphery like a vicious tide going out on a grim shore, the Periphery’s states and banks sunk deeply in the mud of irreversible insolvency. So as to delay the inevitable defaults that would strike huge blows on the tittering northern banks, so-called bailouts were arranged on condition of austerity policies that were as unsustainable as the growth whose collapse led to them.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the only serious institution that the Eurozone has. It was meant to be the guardian of the euro’s credibility but, alas, during both periods (Ponzi growth and Ponzi austerity), the ECB proved incapable of playing this role. When toxic capital flowed disastrously into the Periphery, the ECB whistled in the wind. When it flowed out, causing the collapse that then gave rise to the Ponzi austerity, the ECB was part and parcel of this crime against the peoples and the spirit of Europe. Now that the chickens are coming home to roost, the ECB is pledging to do “all it takes” to save the euro, but fails to back up such strong words with deeds...

MORE AT LINK---EXPLAINS A LOT ABOUT THE EUROZONE MADNESS

August 22, 2012

Last week Vice President Joe Biden did a courageous thing, he promised an audience in southern Virginia that there will be no cuts whatsoever to Social Security in a second Obama Administration. He used the strongest possible language, telling customers at a local diner: “I guarantee you, flat guarantee you, there will be no changes in Social Security. I flat guarantee you.” That was good to hear from the Vice President. Since the Obama Administration had several times indicated that it would be willing to cut Social Security as part of a “Grand Bargain” on the budget, it was encouraging to hear Mr. Biden make such an unambiguous commitment. While nothing in politics can be taken as 100 percent certain, this is about as good as you get.

On the one hand, Biden’s commitment may not seem very courageous. After all, he is running for office and Social Security is the most popular program on the table. It draws approval ratings close to 80 percent from Republicans, conservatives, and even Tea Party supporters. Backing Social Security in this context might just seem like cheap politics, which it may well be. However, Biden also lives in a city where calling for cuts to Social Security is the way to demonstrate your manhood. The bigger the cuts and the more frequent the calls, the higher your status. And, there are plenty of rewards for those politicians who go down fighting for Social Security cuts. Just check out the salaries for the lobbying jobs of the Blue Dog Democrats who have left office in recent years.

The Washington Post immediately got on the job of applying the peer group pressure to Mr. Biden, running an editorial denouncing his lack of “courage.” The editorial repeated the usual points – the trust fund will go broke in just 21 years. Of course this means that we would only be able to pay 80 percent of scheduled benefits rather than 100 percent, if Congress did nothing. And the amount needed to pay full scheduled benefits is considerably less than the annual cost of the war with Iraq. Did we need more than two decades to figure out where the money is going to come from to pay for that war? To put it another way, if the shortfall was made up entirely through higher payroll taxes, the increase would be a bit more than 5 percent of projected wage growth over the next three decades. Are you terrified yet?

Actually the best part of the editorial was when the Post gave its preferred fixes to the projected Social Security shortfall. One of the items it listed was “tweak the inflation calculator,” which it assured us could be done “with no harm to the safety net.” Hey, who could object to tweaking the inflation calculator if that would save Social Security? In case you missed it, “tweaking the inflation calculator” means reducing the annual cost-of-living adjustment by 0.3 percent. That might seem small, but it adds up over time. After 10 years retirees will see a 3 percent decline in benefits, after 20 years the reduction is 6 percent, and those who live to collect benefits for 30 years would see roughly a 9 percent drop in benefits. This isn’t doing harm to the safety net?

The amazing part of the story is that the Post did not have the courage to tell readers that it is proposing a cut in benefits. Instead this editorial on courage used a euphemism whose meaning would likely not be apparent to many of its readers.

KEEP READING AT LINK FOR THE CONCLUSION: IT'S A CORKER!

Courage in Washington Doesn’t Have the Same Meaning By Dean Baker

http://www.nationofchange.org/courage-washington-doesn-t-have-same-meaning-1345554591Last week Vice President Joe Biden did a courageous thing, he promised an audience in southern Virginia that there will be no cuts whatsoever to Social Security in a second Obama Administration. He used the strongest possible language, telling customers at a local diner: “I guarantee you, flat guarantee you, there will be no changes in Social Security. I flat guarantee you.” That was good to hear from the Vice President. Since the Obama Administration had several times indicated that it would be willing to cut Social Security as part of a “Grand Bargain” on the budget, it was encouraging to hear Mr. Biden make such an unambiguous commitment. While nothing in politics can be taken as 100 percent certain, this is about as good as you get.

On the one hand, Biden’s commitment may not seem very courageous. After all, he is running for office and Social Security is the most popular program on the table. It draws approval ratings close to 80 percent from Republicans, conservatives, and even Tea Party supporters. Backing Social Security in this context might just seem like cheap politics, which it may well be. However, Biden also lives in a city where calling for cuts to Social Security is the way to demonstrate your manhood. The bigger the cuts and the more frequent the calls, the higher your status. And, there are plenty of rewards for those politicians who go down fighting for Social Security cuts. Just check out the salaries for the lobbying jobs of the Blue Dog Democrats who have left office in recent years.

The Washington Post immediately got on the job of applying the peer group pressure to Mr. Biden, running an editorial denouncing his lack of “courage.” The editorial repeated the usual points – the trust fund will go broke in just 21 years. Of course this means that we would only be able to pay 80 percent of scheduled benefits rather than 100 percent, if Congress did nothing. And the amount needed to pay full scheduled benefits is considerably less than the annual cost of the war with Iraq. Did we need more than two decades to figure out where the money is going to come from to pay for that war? To put it another way, if the shortfall was made up entirely through higher payroll taxes, the increase would be a bit more than 5 percent of projected wage growth over the next three decades. Are you terrified yet?

Actually the best part of the editorial was when the Post gave its preferred fixes to the projected Social Security shortfall. One of the items it listed was “tweak the inflation calculator,” which it assured us could be done “with no harm to the safety net.” Hey, who could object to tweaking the inflation calculator if that would save Social Security? In case you missed it, “tweaking the inflation calculator” means reducing the annual cost-of-living adjustment by 0.3 percent. That might seem small, but it adds up over time. After 10 years retirees will see a 3 percent decline in benefits, after 20 years the reduction is 6 percent, and those who live to collect benefits for 30 years would see roughly a 9 percent drop in benefits. This isn’t doing harm to the safety net?

The amazing part of the story is that the Post did not have the courage to tell readers that it is proposing a cut in benefits. Instead this editorial on courage used a euphemism whose meaning would likely not be apparent to many of its readers.

KEEP READING AT LINK FOR THE CONCLUSION: IT'S A CORKER!

August 21, 2012

THIS IS A KEEPER--A COMPENDIUM OF ALL THAT'S GONE WRONG IN THE LAST 25 YEARS.....MUST READ!

...Time is running out for prosecutors to file cases against big banks for activities that triggered the 2007-2009 financial crisis, since statutes of limitations set deadlines for launching prosecutions for fraud and other financial crimes. If prosecutors don’t start lawsuits before these deadlines expire, the big banks will, once again, have got off scot-free. Failure to pursue banks, culpable management and employees for their complicity in causing the financial crisis is one of six bad policies that ensure we’re likely to see another bust-up of a big U.S. bank -- sooner rather than later. Who’s going to pay the price for such a failure? We will, of course. Uncle Sam’s policy of allowing banks to get too big to fail means we’ll all be left holding the bag when that collapse occurs — and another banking bailout is necessary.

1. Too big to fail

Thirty years of financial deregulation have seen unprecedented concentration of the financial sector. Before, financial firms were limited both in where they could do business and the types of business they could do. This prevented a big banking blowup in the U.S. for more than 50 years. Banks used to be limited to owning branches within individual states. When a bank got into trouble—and some did -- losses stayed confined. Regulators such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) could clean up the mess and preserve depositors’ assets, without unduly burdening taxpayers. But after changes culminating in the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act in 1994, those restrictions vanished. So some banks got steadily bigger, while the overall number shrank. From 1990 to 2011, the number of commercial banks halved, from about 12,000 to 6,000, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

Once upon a time, the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act limited banks to either commercial or investment banking functions. Brokerage activities were restricted, and the operations of insurance firms constrained. Problems in one area of financial activity didn’t spread to another. Bankers could not speculate with small depositors’ money. Banks competed with each other, which led to better lending terms. And they didn’t get too big, so when they screwed up, they paid the price. They failed. In the 1980s, financial institutions claimed that Glass-Steagall and other restrictions prevented U.S. banks from competing head-to-head with foreign banks. They lobbied hard and regulators began to allow the restrictions slowly to erode...The net effect of all these rule changes – - was that banks became too big to fail. Fear that their failure has led regulators to go soft on the big banks, and to do anything to keep them alive.

2. See no evil, hear no evil

While the financial system was consolidating, another threat was looming: the “shadow banking system“ was being created. Another New Deal reform, the Investment Company Act of 1940, imposed heavy restrictions on investment companies, which were intended to protect investors from excessive risks, fraud and scams. But regulators decided that sophisticated investors, including the wealthy, pension funds and charities, had enough financial savvy to be allowed to invest in shadow banks that were either lightly regulated, or not at all. Such alternative investment vehicles, including hedge funds and private equity funds, were exempt from investment restrictions.

In the last two decades, there’s been an explosive growth in shadow banks. The size of this unregulated system has increased fivefold and today is larger than the regulated financial system. The rationale? Sophisticated investors, it’s claimed, can look after themselves, and therefore the largely unregulated funds that cater to them don’t pose any risks to the rest of us. But that’s not proven to be the case. And, surprise, surprise, when such firms fail, guess who pays the price? We do.

3. Calling in the cavalry, but giving them the wrong directions

Once the U.S. decided to deregulate the financial sector, and banks got bigger, it was inevitable that the government would be called in for a rescue. Most of us were aware that in 2008, the government stepped in to bail out big banks that were destabilized by Lehman Brothers’ collapse and by the bad derivatives bets entered into by AIG Financial Products. The world financial system was at the brink, we were told, and the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) was necessary to save the system. But a decade before this bailout, U.S. financial regulators were involved in a rescue of a shadow bank, which helped set the stage for TARP. In 1998, the Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) hedge fund got into trouble by placing heavily-leveraged derivatives bets during the Asian financial crisis. Hedge funds are allowed to operate with scant regulatory supervision on the rationale that they cater only to sophisticated investors who could bear the risk.

The Federal Reserve changed its mind when it realized that LTCM’s failure was a threat to the global economy. So the Fed corralled major banks in a room, and told them to fix the problem. They dismembered LTCM and took its underperforming assets onto their books. The Fed’s role in this rescue sent the wrong message: that the government would be there to fix problems, and that banks and shadow banks alike didn’t have to work too hard to manage risk and to protect themselves from contagion.

Sometimes you want government intervention to quell a banking panic, and to shore up or reboot a failed banking system. Banks need to be seized, or at minimum assessed by a neutral observer, and their balance sheets cleaned up. Investors, too, must pay a price for making foolish investment choices. Typically, existing shareholders are wiped out, while bondholders see their promises of guaranteed debt payments converted to more speculative shares of stock. We used to know how to do this. The Depression-era Reconstruction Finance Corporation seized failing banks, cleaned up their balance sheets, and later transferred these institutions back to private ownership. The Resolution Trust Corporation followed similar policies in cleaning up the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and early 1990s. More recently, the Swedish government nationalized failing banks in the 1990s. Managers were penalized, and shareholders and sometimes bondholders took losses. But the U.S. forgot all these sound policies in the 2008 TARP. The government provided cash to stabilize shaky financial institutions, guarantees to bondholders, and tax breaks. It also purchased some risky assets. But it didn’t get much in exchange. Regulators didn’t demand that banks open their books and clean up their balance sheets. The big banks continued as going concerns. Bank managers paid no price and mostly kept their jobs. They paid themselves bonuses rather than using capital to shore up their banks. Bottom line: Managers, shareholders, and bondholders didn’t fully pay for their folly.

The government further erred by nudging sound banks to take over failing ones. This policy led to further consolidation of the banking system, making surviving banks even bigger! Finally, the government failed to take action to address the problems that let big financial institutions get into trouble in the first place.

4. Creating financial weapons of mass destruction

5. Companies consolidate, while regulation remains fragmented

6. Perps get off scot-free

SEE LINK FOR THE REST

****************************************************

Alexander Arapoglou, professor of finance at the University of North Carolina's Kenan-Flagler Business School, has been a derivatives trader and head of risk management worldwide for various global financial institutions.

Jerri-Lynn Scofield has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader.

Uncle Sam Needs YOU for a Bailout: 6 Reasons Another Big Banking Crisis Is Coming Our Way

http://www.alternet.org/economy/uncle-sam-needs-you-bailout-6-reasons-another-big-banking-crisis-coming-our-way?akid=9240.227380.rRjx_u&rd=1&src=newsletter695643&t=9&paging=offTHIS IS A KEEPER--A COMPENDIUM OF ALL THAT'S GONE WRONG IN THE LAST 25 YEARS.....MUST READ!

...Time is running out for prosecutors to file cases against big banks for activities that triggered the 2007-2009 financial crisis, since statutes of limitations set deadlines for launching prosecutions for fraud and other financial crimes. If prosecutors don’t start lawsuits before these deadlines expire, the big banks will, once again, have got off scot-free. Failure to pursue banks, culpable management and employees for their complicity in causing the financial crisis is one of six bad policies that ensure we’re likely to see another bust-up of a big U.S. bank -- sooner rather than later. Who’s going to pay the price for such a failure? We will, of course. Uncle Sam’s policy of allowing banks to get too big to fail means we’ll all be left holding the bag when that collapse occurs — and another banking bailout is necessary.

1. Too big to fail

Thirty years of financial deregulation have seen unprecedented concentration of the financial sector. Before, financial firms were limited both in where they could do business and the types of business they could do. This prevented a big banking blowup in the U.S. for more than 50 years. Banks used to be limited to owning branches within individual states. When a bank got into trouble—and some did -- losses stayed confined. Regulators such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) could clean up the mess and preserve depositors’ assets, without unduly burdening taxpayers. But after changes culminating in the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act in 1994, those restrictions vanished. So some banks got steadily bigger, while the overall number shrank. From 1990 to 2011, the number of commercial banks halved, from about 12,000 to 6,000, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

Once upon a time, the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act limited banks to either commercial or investment banking functions. Brokerage activities were restricted, and the operations of insurance firms constrained. Problems in one area of financial activity didn’t spread to another. Bankers could not speculate with small depositors’ money. Banks competed with each other, which led to better lending terms. And they didn’t get too big, so when they screwed up, they paid the price. They failed. In the 1980s, financial institutions claimed that Glass-Steagall and other restrictions prevented U.S. banks from competing head-to-head with foreign banks. They lobbied hard and regulators began to allow the restrictions slowly to erode...The net effect of all these rule changes – - was that banks became too big to fail. Fear that their failure has led regulators to go soft on the big banks, and to do anything to keep them alive.

2. See no evil, hear no evil

While the financial system was consolidating, another threat was looming: the “shadow banking system“ was being created. Another New Deal reform, the Investment Company Act of 1940, imposed heavy restrictions on investment companies, which were intended to protect investors from excessive risks, fraud and scams. But regulators decided that sophisticated investors, including the wealthy, pension funds and charities, had enough financial savvy to be allowed to invest in shadow banks that were either lightly regulated, or not at all. Such alternative investment vehicles, including hedge funds and private equity funds, were exempt from investment restrictions.

In the last two decades, there’s been an explosive growth in shadow banks. The size of this unregulated system has increased fivefold and today is larger than the regulated financial system. The rationale? Sophisticated investors, it’s claimed, can look after themselves, and therefore the largely unregulated funds that cater to them don’t pose any risks to the rest of us. But that’s not proven to be the case. And, surprise, surprise, when such firms fail, guess who pays the price? We do.

3. Calling in the cavalry, but giving them the wrong directions