Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's JournalExclusive: DHS watchdog finds 900 people at border facility with maximum capacity of 125

Source: WRAL

By Priscilla Alvarez, CNN

CNN — The Department of Homeland Security's Inspector General has found "dangerous overcrowding" and unsanitary conditions at an El Paso, Texas, Border Patrol processing facility following an unannounced inspection, according to a report obtained by CNN.

The IG found "standing room only conditions" at the El Paso Del Norte Processing Center, which has a maximum capacity of 125 migrants, but on May 7 and 8, logs indicated that there were "approximately 750 and 900 detainees, respectively."

A cell with a maximum capacity of 12 held 76 detainees, another with a maximum capacity of 8 held 41 detainees, and another with a maximum capacity of 35 held 155 detainees, according to the report.

" (Customs and Border Protection) was struggling to maintain hygienic conditions in the holding cells. With limited access to showers and clean clothing, detainees were wearing soiled clothing for days or weeks," the report states.

"We also observed detainees standing on toilets in the cells to make room and gain breathing space, thus limiting access to the toilets," it adds.

Read more: https://www.wral.com/exclusive-dhs-watchdog-finds-900-people-at-border-facility-with-maximum-capacity-for-125/18422626/

My.Fucking.God!

98 Years Ago Today; Terror and Tragedy in Tulsa

The Tulsa race riot (or the Tulsa race massacre) of 1921 took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of whites attacked black residents and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. This is considered one of the worst incidents of racial violence in the history of the United States. The attack, carried out on the ground and by air, destroyed more than 35 blocks of the district, at the time the wealthiest black community in the United States.

More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals and more than 6,000 black residents were arrested and detained, many for several days. The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead, but the American Red Cross declined to provide an estimate. When a state commission re-examined events in 2001, its report estimated that 100-300 African Americans were killed in the rioting.

The riot began over Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator of the nearby Drexel Building. He was taken into custody. A subsequent gathering of angry local whites outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held, and the spread of rumours he had been lynched, alarmed the local black population, some of whom arrived at the courthouse armed. Shots were fired and twelve people were killed; ten white and two black. As news of these deaths spread throughout the city, mob violence exploded. Thousands of whites rampaged through the black neighborhood that night and the next day, killing men and women, burning and looting stores and homes. About 10,000 black people were left homeless, and property damage amounted to more than $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property ($32 million in 2019).

Many survivors left Tulsa. Black and white residents who stayed in the city were silent for decades about the terror, violence, and losses of this event. The riot was largely omitted from local, state, as well as national, histories: "The Tulsa race riot of 1921 was rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms or even in private. Blacks and whites alike grew into middle age unaware of what had taken place."

In 1996, seventy-five years after the riot, a bi-partisan group in the state legislature authorized formation of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (renamed to Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Massacre in November 2018). Members were appointed to investigate events, interview survivors, hear testimony from the public, and prepare a report of events. There was an effort toward public education about these events through the process. The Commission's final report, published in 2001, said that the city had conspired with the mob of white citizens against black citizens; it recommended a program of reparations to survivors and their descendants. The state passed legislation to establish some scholarships for descendants of survivors, encourage economic development of Greenwood, and develop a memorial park in Tulsa to the riot victims. The park was dedicated in 2010.

Monday, May 30, 1921 – Memorial Day

Encounter in the elevator

It is alleged that at some time about or after 4 PM, 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner employed at a Main Street shine parlor, entered the only elevator of the nearby Drexel Building at 319 South Main Street to use the top-floor restroom, which was restricted to black people. He encountered Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator on duty. The two likely knew each other at least by sight, as this building was the only one nearby with a restroom to which Rowland had express permission to use, and the elevator operated by Page was the only one in the building. A clerk at Renberg's, a clothing store on the first floor of the Drexel, heard what sounded like a woman's scream and saw a young black man rushing from the building. The clerk went to the elevator and found Page in what he said was a distraught state. Thinking she had been assaulted, he summoned the authorities.

The 2001 Oklahoma Commission Final Report notes that it was unusual for both Rowland and Page to be working downtown on Memorial Day, when most stores and businesses were closed. It suggests that Rowland had a simple accident, such as tripping and steadying himself against the girl, or perhaps they were lovers and had a quarrel.

Whether – and to what extent – Dick Rowland and Sarah Page knew each other has long been a matter of speculation. It seems reasonable that they would have least been able to recognize each other on sight, as Rowland would have regularly ridden in Page's elevator on his way to and from the restroom. Others, however, have speculated that the pair might have been lovers – a dangerous and potentially deadly taboo, but not an impossibility. Whether they knew each other or not, it is clear that both Dick Rowland and Sarah Page were downtown on Monday, May 30, 1921 – although this, too, is cloaked in some mystery. On Memorial Day, most – but not all – stores and businesses in Tulsa were closed. Yet, both Rowland and Page were apparently working that day.

Yet in the days and years that followed, many who knew Dick Rowland agreed on one thing: that he would never have been capable of rape.

The word "rape" was rarely used in newspapers or academia in the early 20th century. Instead, "assault" was used to describe such an attack.

Brief investigation

Although the police likely questioned Page, no written account of her statement has been found. It is generally accepted that the police determined what happened between the two teenagers was something less than an assault. The authorities conducted a low-key investigation rather than launching a man-hunt for her alleged assailant. Afterward, Page told the police that she would not press charges.

Regardless of whether assault had occurred, Rowland had reason to be fearful. At the time, such an accusation alone put him at risk for attack by white people. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Rowland fled to his mother's house in the Greenwood neighborhood.

Identity of the black rioters

The Morning Tulsa Daily World reported on the 3rd of June, major points of their interview with Deputy Sheriff Barney Cleaver concerning the events leading up to the Tulsa riot. Cleaver was deputy sheriff for Okmulgee county and not under the supervision of the city police department; his duties mainly involved enforcing law among the "coloured people" of Greenwood but he also operated a business as a private investigator. He had previously been dismissed as an investigator for the city police for assisting county officers with a drug raid at Gurley's Hotel but not reporting his involvement to his superiors. He had considerable land holdings and suffered tremendous financial damages as a result of the riot. Among his holdings were several residential properties and Cleaver Hall, a large community gathering place and function hall. He reported personally evicting a number of armed criminals who had taken to barricading themselves within properties he owned. Upon eviction, they merely moved to Cleaver Hall. Cleaver reported that the majority of violence started at Cleaver Hall along with the rioters barricaded inside.Charles Page offered to build him a new home.

The Morning Tulsa Daily World stated, "Cleaver named Will Robinson, a dope peddler and all around bad negro, as the leader of the armed blacks. He has also the names of three others who were in the armed gang at the court house. The rest of the negroes participating in the fight, he says, were former servicemen who had an exaggerated idea of their own importance... They did not belong here, had no regular employment and were simply a floating element with seemingly no ambition in life but to forment trouble." O. W. Gurley, owner of Gurley's Hotel identified the following men by name as arming themselves and gathering in his hotel: Will Robinson, Peg Leg Taylor, Bud Bassett, Henry Van Dyke, Chester Ross, Jake Mayes, O. B. Mann, John Suplesox, Fatty, Jack Scott, Lee Mable, John Bowman and W. S. Weaver.

Tuesday, May 31, 1921

Suspect arrested

One of the sensationalist news articles that contributed to tensions in Tulsa

On the morning after the incident, Detective Henry Carmichael and Henry C. Pack, a black patrolman, located Rowland on Greenwood Avenue and detained him. Pack was one of two black officers on the city's police force, which then included about 45 officers. Rowland was initially taken to the Tulsa city jail at First and Main. Late that day, Police Commissioner J. M. Adkison said he had received an anonymous telephone call threatening Rowland's life. He ordered Rowland transferred to the more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.

Rowland was well known among attorneys and other legal professionals within the city, many of whom knew Rowland through his work as a shoeshiner. Some witnesses later recounted hearing several attorneys defend Rowland in their conversations with one another. One of the men said, "Why, I know that boy, and have known him a good while. That's not in him."

Newspaper coverage

The Tulsa Tribune, one of two white-owned papers published in Tulsa, broke the story in that afternoon's edition with the headline: "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator", describing the alleged incident. According to some witnesses, the same edition of the Tribune included an editorial warning of a potential lynching of Rowland, entitled "To Lynch Negro Tonight". The paper was known at the time to have a "sensationalist" style of news writing. All original copies of that issue of the paper have apparently been destroyed, and the relevant page is missing from the microfilm copy, so the exact content of the column (and whether it existed at all) remains in dispute.

Stand-off at the courthouse

The afternoon edition of the Tribune hit the streets shortly after 3 p.m., and soon news spread of a potential lynching. By 4 pm, local authorities were on alert. White people began congregating at and near the Tulsa County Courthouse. By sunset at 7:34 pm, the several hundred white people assembled outside the courthouse appeared to have the makings of a lynch mob. Willard M. McCullough, the newly elected sheriff of Tulsa County, was determined to avoid events such as the 1920 lynching of white murder suspect Roy Belton in Tulsa, which had occurred during the term of his predecessor. The sheriff took steps to ensure the safety of Rowland. McCullough organized his deputies into a defensive formation around Rowland, who was terrified. One of Scott Ellsworth's references in the 2001 commission report, The Guthrie Daily Leader, reported that Rowland had been taken to the county jail before crowds started to gather. The sheriff positioned six of his men, armed with rifles and shotguns, on the roof of the courthouse. He disabled the building's elevator, and had his remaining men barricade themselves at the top of the stairs with orders to shoot any intruders on sight. The sheriff went outside and tried to talk the crowd into going home, but to no avail. According to an account by Scott Ellsworth, the sheriff was "hooted down".

About 8:20 pm, three white men entered the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be turned over to them. Although vastly outnumbered by the growing crowd out on the street, Sheriff McCullough turned the men away.

A few blocks away on Greenwood Avenue, members of the black community and known criminals associated with underground gambling houses, gathered to discuss the situation at Gurley's Hotel. Given the recent lynching of Belton, a white man accused of murder, they believed that Rowland was greatly at risk. Many black residents were determined to prevent the crowd from lynching Rowland, but they were divided about tactics. Young World War I veterans prepared for a battle by collecting guns and ammunition. Older, more prosperous men feared a destructive confrontation that likely would cost them dearly. O. W. Gurley gave a sworn statement to the Grand Jury that he tried to convince the men that there would be no lynching but that they had responded that Sheriff McCullough had personally told them that their presence was required. About 9:30 pm, a group of approximately 50-60 black men, armed with rifles and shotguns, arrived at the jail to support the sheriff and his deputies to defend Rowland from the mob. Corroborated by ten witnesses, attorney James Luther submitted to the grand jury that they were following the orders of Sheriff McCullough who publicly denied he gave any orders:

"I saw a car full of negroes driving through the streets with guns; I saw Bill McCullough and told him those negroes would cause trouble; McCullough tried to talk to them, and they got out and stood in single file. W. G. Daggs was killed near Boulder and Sixth street. I was under the impression that a man with authority could have stopped and disarmed them. I saw Chief of Police on south side of court house on top step, talking; I did not see any officer except the Chief; I walked in the court house and met McCullough in about 15 feet of his door; I told him these negroes were going to make trouble, and he said he had told them to go home; he went out and told the whites to go home, and one said "they said you told them to come up here." McCullough said "I did not" and a negro said you did tell us to come."

Taking up arms

Having seen the armed black people, some of the more than 1,000 white people at the courthouse went home for their own guns. Others headed for the National Guard armory at Sixth Street and Norfolk Avenue, where they planned to arm themselves. The armory contained a supply of small arms and ammunition. Major James Bell of the 180th Infantry had already learned of the mounting situation downtown and the possibility of a break-in, and he took measures to prevent the same. He called the commanders of the three National Guard units in Tulsa, who ordered all the Guard members to put on their uniforms and report quickly to the armory. When a group of white people arrived and began pulling at the grating over a window, Bell went outside to confront the crowd of 300 to 400 men. Bell told them that the Guard members inside were armed and prepared to shoot anyone who tried to enter. After this show of force, the crowd withdrew from the armory.

At the courthouse, the crowd had swollen to nearly 2,000, many of them now armed. Several local leaders, including Reverend Charles W. Kerr, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, tried to dissuade mob action. The chief of police, John A. Gustafson, later claimed that he tried to talk the crowd into going home.

Anxiety on Greenwood Avenue was rising. Many blacks worried about the safety of Rowland. Small groups of armed black men ventured toward the courthouse in automobiles, partly for reconnaissance, and to demonstrate they were prepared to take necessary action to protect Rowland.

Many white men interpreted these actions as a "Negro uprising" and became concerned. Eyewitnesses reported gunshots, presumably fired into the air, increasing in frequency during the evening.

Second offer

In Greenwood, rumors began to fly – in particular, a report that white men and women were storming the courthouse. Shortly after 10 pm, a second, larger group of approximately 75 armed black men decided to go to the courthouse. They offered their support to the sheriff, who declined their help. According to witnesses, a white man is alleged to have told one of the armed black men to surrender his pistol. The man refused, and a shot was fired. That first shot may have been accidental, or meant as a warning; it was a catalyst for an exchange of gunfire.

Riot

The gunshots triggered an almost immediate response by the white men, many of whom fired on the black people, who then fired back at the white people. The first "battle" was said to last a few seconds or so, but took a toll, as ten white people and two black people lay dead or dying in the street. The black contingent retreated toward Greenwood. A rolling gunfight ensued. The armed white mob pursued the armed black mob toward Greenwood, with many stopping to loot local stores for additional weapons and ammunition. Along the way, bystanders, many of whom were leaving a movie theater after a show, were caught off guard by the mobs and fled. Panic set in as the white mob began firing on any black people in the crowd. The white mob also shot and killed at least one white man in the confusion.

At around 11 pm, members of the Oklahoma National Guard unit began to assemble at the armory to organize a plan to subdue the rioters. Several groups were deployed downtown to set up guard at the courthouse, police station, and other public facilities. Members of the local chapter of the American Legion joined in on patrols of the streets. The forces appeared to have been deployed to protect the white districts adjacent to Greenwood. The National Guard rounded up numerous black people and took them to the Convention Hall on Brady Street for detention.

Many prominent white Tulsans also participated in the riot[citation needed], including Tulsa founder and KKK member W. Tate Brady, who participated in the riot as a night watchman. It was reported, in This Land Press that W. Tate Brady participated and led the tarring and feathering of a group of men. The article states that police, "delivered the convicted men into the custody of the black-robed Knights of Liberty." The provided document attached to the article states,""I believe the circumstantial evidence is sufficient to prevent any of them from wanting to give anyone any trouble in the way of lawsuits...all made the same statement with emphasis that Tate Brady put on the tar and feathers in the 'name of the women and children of Belgium.' The same is true as to the part that Chief of Police Ed Lucas took. Not all the witnesses said they would swear in court as to...[document incomplete]" The since uncovered remainder of the document continues, "It is a question as to what extent I could go in establishing beyond a doubt the persons in the mob since their disguise with the robes and masks was complete. I doubt if I could do it in a court in Oklahoma at this time." In the Tulsa Daily World article about the incident, the victims were reported to be suspected German spies, referred to as I.W.W.'s. Harlows Weekly also explains the contemporary connection between Belgium, the I.W.W. and the Knights of Liberty. The article sympathetically explains the actions as economically and politically motivated rather than racially motivated. A Kansas detective reported over 200 members of the I.W.W. and their affiliates migrated to Oklahoma to organise an open rebellion among the working class against the war effort planned for November 1, 1917. It was reported that police beat the I.W.W. members before delivering them to the Knights of Liberty. The Tulsa Daily World reported that none of the policemen could identify any of the hooded men. The Tulsa Daily World article states that the policemen were kidnapped, forced to drive the prisoners to a ravine and forced to watch the entire ordeal at gunpoint. Previous reports regarding Brady's character seem favourable and he hired black employees in his businesses. Brady married a Cherokee woman and fought for Cherokee claims against the U.S. government.

At around midnight, white rioters again assembled outside the courthouse. It was a smaller group but more organised and determined. They shouted in support of a lynching. When they attempted to storm the building, the sheriff and his deputies turned them away and dispersed them.

Wednesday, June 1, 1921

Throughout the early morning hours, groups of armed white and black people squared off in gunfights. At this point the fighting was concentrated along sections of the Frisco tracks, a dividing line between the black and white commercial districts. A rumor circulated that more black people were coming by train from Muskogee to help with an invasion of Tulsa. At one point, passengers on an incoming train were forced to take cover on the floor of the train cars, as they had arrived in the midst of crossfire, with the train taking hits on both sides.

Small groups of white people made brief forays by car into Greenwood, indiscriminately firing into businesses and residences. They often received return fire. Meanwhile, white rioters threw lighted oil rags into several buildings along Archer Street, igniting them.

Fires begin

Fires burning along Archer and Greenwood during the Tulsa race riot of 1921

At around 1 am, the white mob began setting fires, mainly in businesses on commercial Archer Street at the southern edge of the Greenwood district. As crews from the Tulsa Fire Department arrived to put out fires, they were turned away at gunpoint. Scott Elsworth makes the same claim, but his reference makes no mention of firefighters. Parrish gave only praise for the national guard. Another reference Elsworth gives to support the claim of holding firefighters at gunpoint is only a summary of events in which they suppressed the firing of guns by the rioters and disarmed them of their firearms. Yet another of his references states that they were fired upon by the black 'mob', "It would mean a fireman's life to turn a stream of water on one of those negro buildings. They shot at us all morning when we were trying to do something but none of my men were hit. There is not a chance in the world to get through that mob into the negro district." By 4 am, an estimated two dozen black-owned businesses had been set ablaze.

As news traveled among Greenwood residents in the early morning hours, many began to take up arms in defense of their neighborhood, while others began a mass exodus from the city. Throughout the night both sides continued fighting, sometimes only sporadically.

Daybreak

Upon sunrise, around 5 a.m., a train whistle sounded (Hirsch said it was a siren). Some rioters believed this sound to be a signal for the rioters to launch an all-out assault on Greenwood. A white man stepped out from behind the Frisco depot and was fatally shot by a sniper in Greenwood. Crowds of rioters poured from their shelter, on foot and by car, into the streets of the black neighborhood. Five white men in a car led the charge, but were killed by a fusillade of gunfire before they had traveled one block.

Overwhelmed by the sheer number of white people, more black people retreated north on Greenwood Avenue to the edge of town. Chaos ensued as terrified residents fled. The rioters shot indiscriminately and killed many residents along the way. Splitting into small groups, they began breaking into houses and buildings, looting. Several black people later testified that white people broke into occupied homes and ordered the residents out to the street, where they could be driven or forced to walk to detention centers.

A rumor spread among the white people that the new Mount Zion Baptist Church was being used as a fortress and armory. Purportedly twenty caskets full of rifles had been delivered to the church, though no evidence was ever found.

Attack by air

Numerous eyewitnesses described airplanes carrying white assailants, who fired rifles and dropped firebombs on buildings, homes, and fleeing families. The privately owned aircraft were dispatched from the nearby Curtiss-Southwest Field outside Tulsa.

Law enforcement officials later said that the planes were to provide reconnaissance and protect against a "Negro uprising". Law enforcement personnel were thought to be aboard at least some flights. Eyewitness accounts, such as testimony from the survivors during Commission hearings and a manuscript by eyewitness and attorney Buck Colbert Franklin discovered in 2015, said that on the morning of June 1, men in the planes dropped incendiary bombs and fired rifles at black residents.

Richard S. Warner concluded in his submission to The Oklahoma Commission that there was no reliable evidence to support such attacks. Many supposed eyewitnesses, many years later reported witnessing explosions. Warner states that many newspapers targeted at black readers heavily reported the use of nitroglycerin, turpentine and rifles from the planes however many cited anonymous sources or second hand accounts from anonymous sources. Beryl Ford, one of the preeminent historians of the disaster, concluded from her vast collection of photographs that there was no evidence of any building damaged by explosions. Danney Goble commended Warner on his efforts and supported his conclusions. State representative Don Ross however dissented from the evidence presented in the report and the conclusions of three of Oklahoma's top experts concluding that bombs were dropped from planes.

William Joseph Simmons, Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, was appointed head of The Knights of the Air, May 20, 1921. The organization was described as a fraternal organisation for former air force officers. A spokesperson for the organisation publicly denounced the Ku Klux Klan and denied any connection.

New eyewitness account

In 2015, a previously unknown written eyewitness account of the events of May 31, 1921 was discovered and subsequently obtained by the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The 10-page typewritten manuscript was authored by noted Oklahoma attorney Buck Colbert Franklin.

Notable quotes:

Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.

"Planes circling in mid-air: They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top."

'The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught fire from the top.'"

I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. 'Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?' I asked myself. 'Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?'

Franklin states that every time he saw a white man shot, he "felt happy" and he, "swelled with pride and hope for the race."

Franklin reported seeing multiple machine guns firing at night and hearing 'thousands and thousands of guns' being fired simultaneously from all directions. He states that he was arrested by, "a thousand boys, it seemed,...firing their guns every step they took."

Arrival of National Guard troops

National Guard with wounded.

Adjutant General Charles Barrett of the Oklahoma National Guard arrived with 109 troops from Oklahoma City by special train about 9:15 am. Ordered in by the governor, he could not legally act until he had contacted all the appropriate local authorities, including the mayor T. D. Evans, the sheriff, and the police chief. Meanwhile, his troops paused to eat breakfast. Barrett summoned reinforcements from several other Oklahoma cities.

By this time, thousands of surviving black residents had fled the city; another 4,000 persons had been rounded up and detained at various centers. Under the martial law established this day, these detainees were required to carry identification cards.

Barrett declared martial law at 11:49 am, and by noon the troops had managed to suppress most of the remaining violence. A 1921 letter from an officer of the Service Company, Third Infantry, Oklahoma National Guard, who arrived May 31, 1921, reported numerous events related to suppression of the riot:

taking about 30-40 blacks into custody;

putting a machine gun on a truck and taking it on patrol;

being fired on from Negro snipers from the "Church" and returning fire; *

being fired on by white men;

turning the prisoners over to deputies to take them to police headquarters;

being fired upon again by negroes and having two NCOs slightly wounded;

searching for negroes and firearms;

detailing a NCO to take 170 Negroes to the civil authorities; and

delivering an additional 150 Negroes to the Convention Hall.

Stockpiled ammunition

Captain John W. McCune reported that stockpiled ammunition within the burning structures began to explode which may have further contributed to casualties.

End of martial law

Martial law was withdrawn Friday afternoon, June 4, 1921 under Field Order No. 7.

Aftermath

Little Africa on Fire. Tulsa Race Riot, June 1, 1921 Apparently taken from the roof of the Hotel Tulsa on 3rd St. between Boston Ave. and Cincinnati Ave. The first row of buildings is along 2nd St. The smoke cloud on the left (Cincinnati Ave. and the Frisco Tracks) is identified in the Tulsa Tribune version of this photo as being where the fire started.

Casualties

The riot was covered by national newspapers and the reported number of deaths varies widely. On June 1, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune reported that nine white people and 68 black people had died in the riot, but shortly afterwards it changed this number to a total of 176 dead. The next day, the same paper reported the count as nine white people and 21 black people. The New York Times said that 77 people had been killed, including 68 black people, but it later lowered the total to 33. The Richmond Times Dispatch of Virginia reported that 85 people (including 25 white people) were killed; it also reported that the Police Chief had reported to Governor Robertson that the total was 75; and that a Police Major put the figure at 175. The Oklahoma Department of Vital Statistics count put the number of deaths at 36 (26 black and 10 white). very few people, if any, died as a direct result of the fire. Official state records recorded only five deaths by conflagration for the entire state in the year of 1921.

Walter Francis White of the N.A.A.C.P. traveled to Tulsa from New York and reported that, although officials and undertakers said that the fatalities numbered ten white and 21 colored, he estimated the number of the dead to be 50 whites and between 150 and 200 Negroes; he also reported that ten white men were killed on Tuesday; six white men drove into the black section and never came out, and thirteen whites were killed on Wednesday; he reported that the head of the Salvation Army in Tulsa said that 37 negroes were employed as gravediggers to bury 120 negroes in individual graves without coffins on Friday and Saturday. The Oklahoma Commission report states that it was 150 graves and over 36 grave diggers. Ground penetrating radar was used to investigate the sites purported to contain these mass graves. Multiple eyewitness reports and 'oral histories' suggested the graves could have been dug at three different cemeteries across the city. The sites were examined and no evidence of ground disturbance indicative of mass graves was found however at one site ground disturbance was found in a five-meter squared area but cemetery records indicate that three graves had been dug and bodies buried within this envelope before the riot. The Los Angeles Express headline said "175 Killed, Many Wounded". Oklahoma's 2001 Commission into the riot placed the number of dead to likely be somewhere between 100-300 people. However this is based on a misquotation of the Red Cross Report, wherein the author states that the total number "is a matter of conjecture."

Of the some 800 people admitted to local hospitals for injuries, the majority are believed to have been white[citation needed], as both black hospitals had been burned in the rioting. Additionally, even if the white hospitals had admitted black people because of the riot, against their usual segregation policy, injured blacks had little means to get to these hospitals, which were located across the city from Greenwood. More than 6,000 black Greenwood residents were arrested and detained at three local facilities: Convention Hall, now known as the Brady Theater, the Tulsa County Fairgrounds (then located about a mile northeast of Greenwood), and McNulty Park (a baseball stadium at Tenth Street and Elgin Avenue).

Red Cross

The Red Cross, in their preliminary overview, mentioned wide-ranging external estimates of 55 to 300 dead however due to the hurried nature of undocumented burials declined to suggest an estimate of their own stating, "The number of dead is a matter of conjecture." The Red Cross registered 8624 persons, recorded 1256 residences burned and a further 215 residences looted as a part of their relief effort. 183 people were hospitalised, mostly for gunshot wounds or burns (they differentiate in their records on the basis of triage category not the type of wound) while a further 531 required first aid or surgical treatment with an estimated 10 000 persons left homeless. 8 miscarriages were attributed to be a result of the tragedy. 19 died in care between June 1 and the 30th of December.

</snip>

I lived in Tulsa 30 years ago, and frequented a laundromat on Brady St where I met a man (caretaker of the laundromat) who was 10 at the time of the riots. I'd never heard of the event until I spoke to him, at length, about his experience during it. I still remember him saying, "You know, I had a lot of rage for a long time about it. I hated white people, but hate can't last forever. And I like you."

Trump says Rolling Thunder ride will return to DC, organizers say not so fast

Washington (CNN)As hundreds of thousands of motorcyclists arrive in the nation's capital Sunday to participate in the final Rolling Thunder, where they pay tribute to service members killed in action or taken as prisoners of war, President Donald Trump says the event will continue next year -- even as the group's president says the annual event is set to end.

"The Great Patriots of Rolling Thunder WILL be coming back to Washington, D.C. next year, & hopefully for many years to come. It is where they want to be, & where they should be. Have a wonderful time today. Thank you to our great men & women of the Pentagon for working it out!" Trump tweeted Sunday morning.

I'm sure he thought they'd be in the front row of his Brown Shirts.

Beschloss Tweet; Admit the bearer

Michael Beschloss✔

@BeschlossDC

Pre-printed ticket for House of Representatives consideration of Richard Nixon’s impeachment, August 1974—never used because Nixon resigned:

9:28 AM - May 26, 2019

I think Mr Beschloss is trying to tell us something.

52 Years Ago Today; "It was 20 years ago today..."

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is the eighth studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. Released on 26 May 1967 in the United Kingdom and 2 June 1967 in the United States, it spent 27 weeks at number one on the UK Albums Chart and 15 weeks at number one in the US. It was lauded by critics for its innovations in production, songwriting and graphic design, for bridging a cultural divide between popular music and high art, and for providing a musical representation of its generation and the contemporary counterculture. It won four Grammy Awards in 1968, including Album of the Year, the first rock LP to receive this honour.

In August 1966, the Beatles permanently retired from touring and began a three-month holiday. During a return flight to London in November, Paul McCartney had an idea for a song involving an Edwardian military band that formed the impetus of the Sgt. Pepper concept. Sessions began on 24 November at EMI's Abbey Road Studios with two compositions inspired by the Beatles' youth, "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "Penny Lane", but after pressure from EMI, the songs were released as a double A-side single and not included on the album.

In February 1967, after recording the title track "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band", McCartney suggested that the Beatles should release an entire album representing a performance by the fictional Sgt. Pepper band. This alter ego group would give them the freedom to experiment musically. During the recording sessions, the band furthered the technological progression they had made with their 1966 album Revolver. Knowing they would not have to perform the tracks live, they adopted an experimental approach to composition and recording on songs such as "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds", "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" and "A Day in the Life". Producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick helped realise the group's ideas by approaching the studio as an instrument, applying orchestral overdubs, sound effects and other methods of tape manipulation. Recording was completed on 21 April 1967. The cover, depicting the Beatles posing in front of a tableau of celebrities and historical figures, was designed by the British pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth.

Sgt. Pepper is regarded by musicologists as an early concept album that advanced the use of extended form in popular music while continuing the artistic maturation seen on the Beatles' preceding releases. It is described as one of the first art rock LPs, aiding the development of progressive rock, and is credited with marking the beginning of the album era. An important work of British psychedelia, the album incorporates a range of stylistic influences, including vaudeville, circus, music hall, avant-garde, and Western and Indian classical music. In 2003, the Library of Congress placed Sgt. Pepper in the National Recording Registry as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". That year, Rolling Stone ranked it number one in its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". As of 2011, it has sold more than 32 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling albums. Professor Kevin Dettmar, writing in The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, described it as "the most important and influential rock-and-roll album ever recorded".

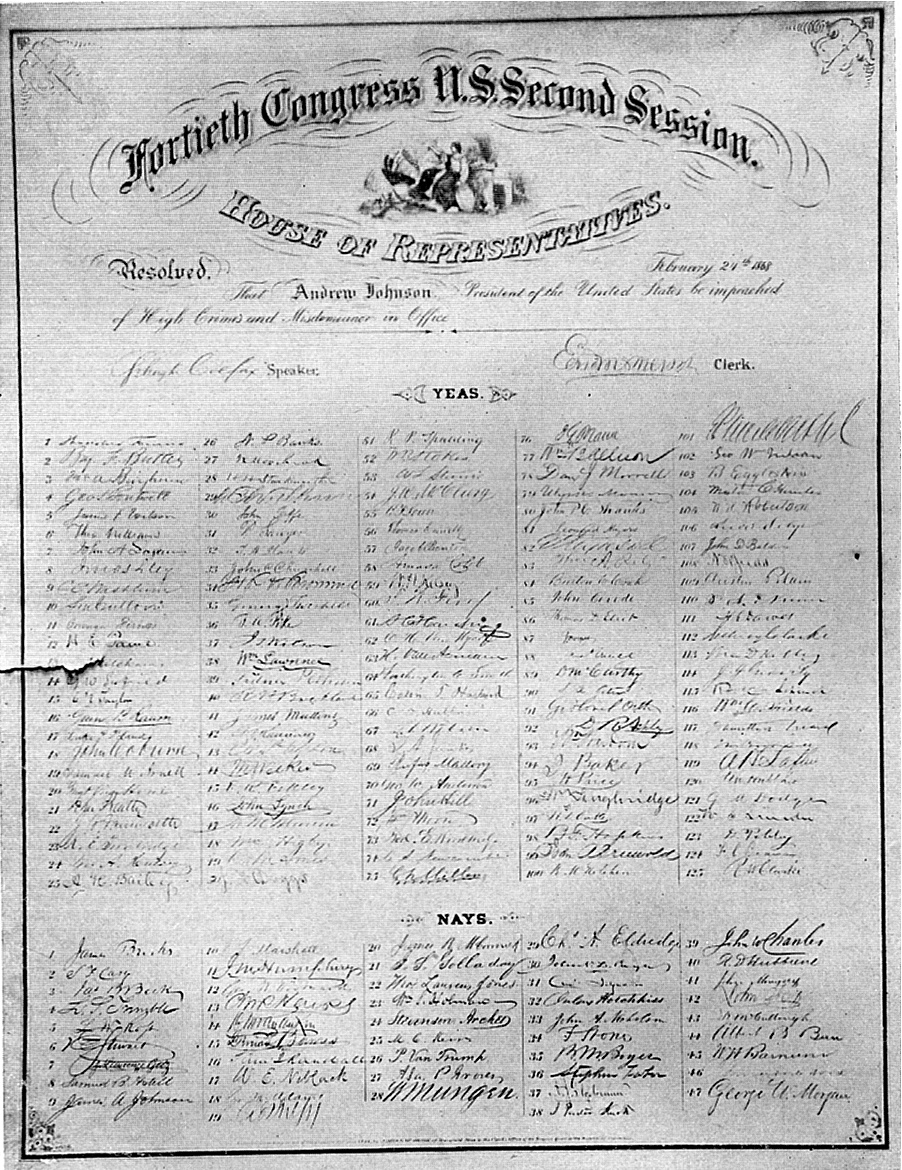

151 Years Ago Today; Senate Trial of Andrew Johnson ends with his acquittal... by one vote

Theodore R. Davis's illustration of President Johnson's impeachment trial in the Senate, published in Harper's Weekly.

Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States, was impeached on February 24, 1868, when the United States House of Representatives resolved to impeach the President, adopting eleven articles of impeachment detailing his "high crimes and misdemeanors", in accordance with Article Two of the United States Constitution. The House's primary charge against Johnson was violation of the Tenure of Office Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in March 1867, over the President's veto. Specifically, he had removed from office Edwin McMasters Stanton, the Secretary of War—whom the Act was largely designed to protect—and attempted to replace him with Brevet Major General Lorenzo Thomas. (Earlier, while the Congress was not in session, Johnson had suspended Stanton and appointed General Ulysses S. Grant as Secretary of War ad interim.)

The House approved the articles of impeachment on March 2–3, 1868, and forwarded them to the Senate. The trial in the Senate began three days later, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding. On May 16, the Senate failed to convict Johnson on one of the articles, with the 35–19 vote in favor of conviction falling short of the necessary two-thirds majority by a single vote. A ten-day recess was called before attempting to convict him on additional articles. The delay did not change the outcome, however, as on May 26, it failed to convict the President on two articles, both by the same margin; after which the trial was adjourned.

This was the first impeachment of a President since creation of the office in 1789. The culmination of a lengthy political battle between Johnson, a lifelong Democrat, and the Republican majority in Congress over how best to deal with the defeated Southern states following the conclusion of the American Civil War, the impeachment and subsequent trial (and acquittal) of Johnson were among the most dramatic events in the political life of the nation during the Reconstruction Era. Together, they have gained a historical reputation as an act of political expedience rather than necessity, based on Johnson's defiance of an unconstitutional piece of legislation and conducted with little regard for the will of a general public which, despite the unpopularity of Johnson, opposed the impeachment.

Johnson is one of only three presidents against whom articles of impeachment have been reported to the full House for consideration. In 1974, during the Watergate scandal, the House Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon, who resigned from office rather than face certain impeachment by the full House and the almost certain prospect of being convicted at trial in the Senate and removed from office with loss of pension and other benefits. In 1998, Bill Clinton was in fact impeached; he, like Johnson, was acquitted of all charges following a Senate trial (with 50 votes for conviction and 50 for acquittal on the count eliciting the most votes for removal).

Background

Presidential Reconstruction

President Andrew Johnson

Tension between the executive and legislative branches had been high prior to Johnson's ascension to the presidency. Following Union Army victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July 1863, President Lincoln began contemplating the issue of how to bring the South back into the Union. He wished to offer an olive branch to the rebel states by pursuing a lenient plan for their reintegration. The forgiving tone of the president's plan, plus the fact that he implemented it by presidential directive without consulting Congress, incensed Radical Republicans, who countered with a more stringent plan. Their proposal for Southern reconstruction, the Wade–Davis Bill, passed both houses of Congress in July 1864, but was pocket vetoed by the president and never took effect.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, just days after the Army of Northern Virginia's surrender at Appomattox briefly lessened the tension over who would set the terms of peace. The radicals, while suspicious of the new president and his policies, believed, based upon his record, that Andrew Johnson would defer, or at least acquiesce to their hardline proposals. Though a Democrat from Tennessee, Johnson had been a fierce critic of the Southern secession. Then after several states left the Union, including his own, he chose to stay in Washington (rather than resign his U.S. Senate seat), and later, when Union troops occupied Tennessee, Johnson was appointed military governor. While in that position he had exercised his powers with vigor, frequently stating that "treason must be made odious and traitors punished". Johnson, however, embraced Lincoln's more lenient policies, thus rejecting the Radicals, and setting the stage for a showdown between the president and Congress. During the first months of his presidency, Johnson issued proclamations of general amnesty for most former Confederates, both government and military officers, and oversaw creation of new governments in the hitherto rebellious states – governments dominated by ex-Confederate officials. In February 1866, Johnson vetoed legislation extending the Freedmen's Bureau and expanding its powers; Congress was unable to override the veto. Afterward, Johnson denounced Radical Republicans Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner, along with abolitionist Wendell Phillips, as traitors. Later, Johnson vetoed a Civil Rights Act and a second Freedmen's Bureau bill; the Senate and the House each mustered the two-thirds majorities necessary to override both vetoes, setting the stage for a showdown between Congress and the president.

At an impasse with Congress, Johnson offered himself directly to the American public as a "tribune of the people". In the late-summer of 1866, the president embarked on a national "Swing Around the Circle" speaking tour, where he asked his audiences for their support in his battle against the Congress and urged voters to elect representatives to Congress in the upcoming midterm election who supported his policies. The tour backfired on Johnson, however, when reports of his undisciplined, vitriolic speeches and ill-advised confrontations with hecklers swept the nation. Contrary to his hopes, the 1866 elections led to veto-proof Republican majorities in both houses of Congress. As a result, Radicals were able to take control of Reconstruction, passing a series of Reconstruction Acts—each one over the President's veto—addressing requirements for Southern states to be fully restored to the Union. The first of these acts divided those states, excluding Johnson's home state of Tennessee, into five military districts, and each state's government was put under the control of the U.S. military. Additionally, these states were required to enact new constitutions, ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, and guarantee voting rights for black males.

Tenure of Office Act

Congress's control of the military Reconstruction policy was mitigated by Johnson's command of the military as president; however, Johnson had inherited, as Secretary of War, Lincoln's appointee Edwin M. Stanton, a staunch Radical Republican, who as long as he remained in office would comply with Congressional Reconstruction policies. To ensure that Stanton would not be replaced, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867 over Johnson's veto. The act required the President to seek the Senate's advice and consent before relieving or dismissing any member of his Cabinet (an indirect reference to Stanton) or, indeed, any federal official whose initial appointment had previously required its advice and consent.

"The Situation", a Harper's Weekly editorial cartoon shows Secretary of War Stanton aiming a cannon labeled "Congress" to defeat Johnson. The rammer is "Tenure of Office Bill" and cannonballs on the floor are "Justice".

Because the Tenure of Office Act did permit the President to suspend such officials when Congress was out of session, when Johnson failed to obtain Stanton's resignation, he instead suspended Stanton on August 5, 1867, which gave him the opportunity to appoint General Ulysses S. Grant, then serving as Commanding General of the Army, interim Secretary of War. When the Senate adopted a resolution of non-concurrence with Stanton's dismissal in December 1867, Grant told Johnson he was going to resign, fearing punitive legal action. Johnson assured Grant that he would assume all responsibility in the matter, and asked him to delay his resignation until a suitable replacement could be found. Contrary to Johnson's belief that Grant had agreed to remain in office, when the Senate voted and reinstated Stanton in January 1868, Grant immediately resigned, before the president had an opportunity to appoint a replacement. Johnson was furious at Grant, accusing him of lying during a stormy cabinet meeting. The March 1868 publication of several angry messages between Johnson and Grant led to a complete break between the two. As a result of these letters, Grant solidified his standing as the frontrunner for the 1868 Republican presidential nomination.

Johnson agonized about Stanton's restoration to office, and undertook a desperate search for someone to replace Stanton whom the Senate might find acceptable. He turned first to General William Tecumseh Sherman, who was an enemy of Stanton's, but Sherman turned the president down. Sherman subsequently suggested to Johnson that Republican radicals and moderates would be amenable to replacing Stanton with Jacob Cox, but he found the president to be no longer interested in appeasement. On February 21, 1868, the president appointed Lorenzo Thomas, a brevet major general in the Army, as interim Secretary of War, ordered the removal of Stanton from office, and informed the Senate of his actions. Thomas personally delivered the president's dismissal notice to Stanton, who refused either to accept its legitimacy or to vacate the premises. Instead, Stanton informed Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax and President pro tempore of the Senate Benjamin Wade of his plight, then barricaded himself in his office and ordered Thomas arrested for violating the Tenure of Office Act. Thomas remained under arrest for several days, until Stanton, realizing that the case against Thomas would provide the courts with an opportunity to review the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, had the charges dropped.

Johnson's opponents in Congress were outraged by his actions; the president's challenge to congressional authority—with regard to both the Tenure of Office Act and post-war reconstruction—had, in their estimation, been tolerated for long enough. In swift response, an impeachment resolution was introduced in the House by representatives Thaddeus Stevens and John Bingham. Expressing the widespread sentiment among House Republicans, Representative William D. Kelley (on February 22, 1868) declared:

Sir, the bloody and untilled fields of the ten unreconstructed states, the unsheeted ghosts of the two thousand murdered negroes in Texas, cry, if the dead ever evoke vengeance, for the punishment of Andrew Johnson.

Impeachment

The impeachment resolution against Andrew Johnson, approved by the House of Representatives on February 24, 1868.

On February 24, 1868 three days after Johnson's dismissal of Stanton, the House of Representatives voted 126 to 47 (with 17 members not voting) in favor of a resolution to impeach the President for high crimes and misdemeanors. Thaddeus Stevens addressed the House prior to the vote. "This is not to be the temporary triumph of a political party," he said, "but is to endure in its consequence until this whole continent shall be filled with a free and untrammeled people or shall be a nest of shrinking, cowardly slaves."

One week later, the House adopted eleven articles of impeachment against the President. The articles charged Johnson with:

Dismissing Edwin Stanton from office after the Senate had voted not to concur with his dismissal and had ordered him reinstated.

Appointing Thomas Secretary of War ad interim despite the lack of vacancy in the office, since the dismissal of Stanton had been invalid.

Appointing Thomas without the required advice and consent of the Senate.

Conspiring, with Thomas and "other persons to the House of Representatives unknown", to unlawfully prevent Stanton from continuing in office.

Conspiring to unlawfully curtail faithful execution of the Tenure of Office Act.

Conspiring to "seize, take, and possess the property of the United States in the Department of War".

Conspiring to "seize, take, and possess the property of the United States in the Department of War" with specific intent to violate the Tenure of Office Act.

Issuing to Thomas the authority of the office of Secretary of War with unlawful intent to "control the disbursements of the moneys appropriated for the military service and for the Department of War".

Issuing to Major General William H. Emory orders with unlawful intent to violate federal law requiring all military orders to be issued through the General of the Army.

Making three speeches with intent to "attempt to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach, the Congress of the United States".

Bringing disgrace and ridicule to the presidency by his aforementioned words and actions.

<snip>

Testimony

The House impeachment committee (from a photograph by Mathew Brady), seated (left to right): Benjamin F. Butler, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams, John A. Bingham, standing (left to right): James F. Wilson, George S. Boutwell, John A. Logan

On the first day, Johnson's defense committee asked for 40 days to collect evidence and witnesses since the prosecution had had a longer amount of time to do so, but only 10 days were granted. The proceedings began on March 23. Senator Garrett Davis argued that because not all states were represented in the Senate the trial could not be held and that it should therefore be adjourned. The motion was voted down. After the charges against the president were made, Henry Stanbery asked for another 30 days to assemble evidence and summon witnesses, saying that in the 10 days previously granted there had only been enough time to prepare the president's reply. John A. Logan argued that the trial should begin immediately and that Stanberry was only trying to stall for time. The request was turned down in a vote 41 to 12. However, the Senate voted the next day to give the defense six more days to prepare evidence, which was accepted.

The trial commenced again on March 30. Benjamin F. Butler opened for the prosecution with a three-hour speech reviewing historical impeachment trials, dating from King John of England. For days Butler spoke out against Johnson's violations of the Tenure of Office Act and further charged that the president had issued orders directly to Army officers without sending them through General Grant. The defense argued that Johnson had not violated the Tenure of Office Act because President Lincoln did not reappoint Stanton as Secretary of War at the beginning of his second term in 1865 and that he was therefore a leftover appointment from the 1860 cabinet, which removed his protection by the Tenure of Office Act. The prosecution called several witnesses in the course of the proceedings until April 9, when they rested their case.

Benjamin R. Curtis called attention to the fact that after the House passed the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate had amended it, meaning that it had to return it to a Senate–House conference committee to resolve the differences. He followed up by quoting the minutes of those meetings, which revealed that while the House members made no notes about the fact, their sole purpose was to keep Stanton in office, and the Senate had disagreed. The defense then called their first witness, Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. He did not provide adequate information in the defense's cause and Butler made attempts to use his information to the prosecution's advantage. The next witness was General William T. Sherman, who testified that President Johnson had offered to appoint Sherman to succeed Stanton as Secretary of War in order to ensure that the department was effectively administered. This testimony damaged the prosecution, which expected Sherman to testify that Johnson offered to appoint Sherman for the purpose of obstructing the operation, or overthrow, of the government. Sherman essentially affirmed that Johnson only wanted him to manage the department and not to execute directions to the military that would be contrary to the will of Congress.

Verdict

The Senate was composed of 54 members representing 27 states (10 former Confederate states had not yet been readmitted to representation in the Senate) at the time of the trial. At its conclusion, senators voted on three of the articles of impeachment. On each occasion the vote was 35–19, with 35 senators voting guilty and 19 not guilty. As the constitutional threshold for a conviction in an impeachment trial is a two-thirds majority guilty vote—in this case 36 votes—Johnson was not removed from office.

Seven Republican senators were concerned that the proceedings had been manipulated to give a one-sided presentation of the evidence. Senators William Pitt Fessenden (Maine), Joseph S. Fowler (Tennessee), James W. Grimes (Iowa), John B. Henderson (Missouri), Lyman Trumbull (Illinois), Peter G. Van Winkle (West Virginia), and Edmund G. Ross (Kansas), who provided the decisive vote, defied their party by voting against conviction. In addition to the aforementioned seven, three more Republicans James Dixon (Connecticut), James Doolittle (Wisconsin), Daniel Norton (Minnesota), and all nine Democratic Senators voted not guilty.

Judgement of the Senate

The first vote was taken on May 16 for the eleventh article. Prior to the vote, Samuel Pomeroy, the senior senator from Kansas, told the junior Kansas Senator Ross that if Ross voted for acquittal that Ross would become the subject of an investigation for bribery. Afterward, in hopes of persuading at least one senator who voted not guilty to change his vote, the Senate adjourned for 10 days before continuing voting on the other articles. During the hiatus, under Butler's leadership, the House put through a resolution to investigate alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate". Despite the Radical Republican leadership's heavy-handed efforts to change the outcome, when votes were cast on May 26 for the second and third articles, the results were the same as the first. After the trial, Butler conducted hearings on the widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal. In Butler's hearings, and in subsequent inquiries, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash cards. Nonetheless, the investigations never resulted in charges, much less convictions, against anyone.

Moreover, there is evidence that the prosecution attempted to bribe the senators voting for acquittal to switch their votes to conviction. Maine Senator Fessenden was offered the Ministership to Great Britain. Prosecutor Butler said, "Tell [Kansas Senator Ross] that if he wants money there is a bushel of it here to be had." Butler's investigation also boomeranged when it was discovered that Kansas Senator Pomeroy, who voted for conviction, had written a letter to Johnson's Postmaster General seeking a $40,000 bribe for Pomeroy's acquittal vote along with three or four others in his caucus. Benjamin Butler was himself told by Ben Wade that Wade would appoint Butler as Secretary of State when Wade assumed the Presidency after a Johnson conviction. An opinion that Senator Ross was mercilessly persecuted for his courageous vote to sustain the independence of the Presidency as a branch of the Federal Government is the subject of an entire chapter in President John F. Kennedy's book, Profiles in Courage. That opinion has been rejected by some scholars, such as Ralph Roske, and endorsed by others, such as Avery Craven.

Not one of the Republican senators who voted for acquittal ever again served in an elective office. Although they were under intense pressure to change their votes to conviction during the trial, afterward public opinion rapidly shifted around to their viewpoint. Some senators who voted for conviction, such as John Sherman and even Charles Sumner, later changed their minds.

</snip>

Interesting parallels to today...

79 Years Ago Today; Operation Dynamo - The Evacuation at Dunkirk

The Dunkirk evacuation, code-named Operation Dynamo, also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, was the evacuation of Allied soldiers during World War II from the beaches and harbour of Dunkirk, in the north of France, between 26 May and 4 June 1940. The operation commenced after large numbers of Belgian, British, and French troops were cut off and surrounded by German troops during the six-week long Battle of France. In a speech to the House of Commons, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called this "a colossal military disaster", saying "the whole root and core and brain of the British Army" had been stranded at Dunkirk and seemed about to perish or be captured. In his "we shall fight on the beaches" speech on 4 June, he hailed their rescue as a "miracle of deliverance".

After Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, France and the British Empire declared war on Germany and imposed an economic blockade. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to help defend France. After the Phoney War of October 1939 to April 1940, Germany invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France on 10 May 1940. Three of their panzer corps attacked through the Ardennes and drove northwest to the English Channel. By 21 May German forces had trapped the BEF, the remains of the Belgian forces, and three French field armies along the northern coast of France. The commander of the BEF, General Viscount Gort, immediately saw evacuation across the Channel as the best course of action, and began planning a withdrawal to Dunkirk, the closest good port.

Late on 23 May, a halt order was issued by Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group A. Adolf Hitler approved the order the next day and had the German High Command send confirmation to the front. Destroying the trapped BEF, French, and Belgian armies was left to the Luftwaffe until the order was rescinded on 26 May. This gave trapped Allied forces time to construct defensive works and pull back large numbers of troops to fight the Battle of Dunkirk. From 28 to 31 May, in the Siege of Lille, the remaining 40,000 men of the once-formidable French First Army fought a delaying action against seven German divisions, including three armoured divisions.

On the first day only 7,669 Allied soldiers were evacuated, but by the end of the eighth day, 338,226 of them had been rescued by a hastily assembled fleet of over 800 boats. Many troops were able to embark from the harbour's protective mole onto 39 British Royal Navy destroyers, four Royal Canadian Navy destroyers, and a variety of civilian merchant ships, while others had to wade out from the beaches, waiting for hours in shoulder-deep water. Some were ferried to the larger ships by what came to be known as the Little Ships of Dunkirk, a flotilla of hundreds of merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, yachts, and lifeboats called into service from Britain. The BEF lost 68,000 soldiers during the French campaign and had to abandon nearly all of its tanks, vehicles, and equipment. In his speech to the House of Commons on 4 June, Churchill reminded the country that "we must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations."

<snip>

Evacuation

26–27 May

The retreat was undertaken amid chaotic conditions, with abandoned vehicles blocking the roads and a flood of refugees heading in the opposite direction. Due to wartime censorship and the desire to keep up British morale, the full extent of the unfolding disaster at Dunkirk was not initially publicised. A special service attended by King George VI was held in Westminster Abbey on 26 May, which was declared a national day of prayer. The Archbishop of Canterbury led prayers "for our soldiers in dire peril in France". Similar prayers were offered in synagogues and churches throughout the UK that day, confirming to the public their suspicion of the desperate plight of the troops. Just before 19:00 on 26 May, Churchill ordered Dynamo to begin, by which time 28,000 men had already departed. Initial plans called for the recovery of 45,000 men from the BEF within two days, at which time German troops were expected to block further evacuation. Only 25,000 men escaped during this period, including 7,669 on the first day.

Troops evacuated from Dunkirk arrive at Dover, 31 May 1940

On 27 May, the first full day of the evacuation, one cruiser, eight destroyers, and 26 other craft were active. Admiralty officers combed nearby boatyards for small craft that could ferry personnel from the beaches out to larger craft in the harbour, as well as larger vessels that could load from the docks. An emergency call was put out for additional help, and by 31 May nearly four hundred small craft were voluntarily and enthusiastically taking part in the effort.

The same day, the Luftwaffe heavily bombed Dunkirk, both the town and the dock installations. As the water supply was knocked out, the resulting fires could not be extinguished. An estimated thousand civilians were killed, one-third of the remaining population of the town. The Luftwaffe was met by 16 squadrons of the Royal Air Force, who claimed 38 kills on 27 May while losing 14 aircraft. Many more RAF fighters sustained damage and were subsequently written off. On the German side, Kampfgeschwader 2 (KG 2) and KG 3 suffered the heaviest casualties. German losses amounted to 23 Dornier Do 17s. KG 1 and KG 4 bombed the beach and harbour and KG 54 sank the 8,000-ton steamer Aden. Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers sank the troopship Cote d' Azur. The Luftwaffe engaged with 300 bombers which were protected by 550 fighter sorties, and attacked Dunkirk in twelve raids. They dropped 15,000 high explosive and 30,000 incendiary bombs, destroying the oil tanks and wrecking the harbour.[74] No. 11 Group RAF flew 22 patrols with 287 aircraft this day, in formations of up to 20 aircraft.

Altogether, over 3,500 sorties were flown in support of Operation Dynamo. The RAF continued to take a heavy toll on the German bombers throughout the week. Soldiers being bombed and strafed while awaiting transport were for the most part unaware of the efforts of the RAF to protect them, as most of the dogfights took place far from the beaches. As a result, many British soldiers bitterly accused the airmen of doing nothing to help.

On 25 and 26 May, the Luftwaffe focused their attention on Allied pockets holding out at Calais, Lille, and Amiens, and did not attack Dunkirk. Calais, held by the BEF, surrendered on 26 May. Remnants of the French First Army, surrounded at Lille, fought off seven German divisions (several of them armoured) until 31 May, when the remaining 35,000 soldiers were forced to surrender after running out of food and ammunition. The Germans accorded the honours of war to the defenders of Lille in recognition of their bravery.

</snip>

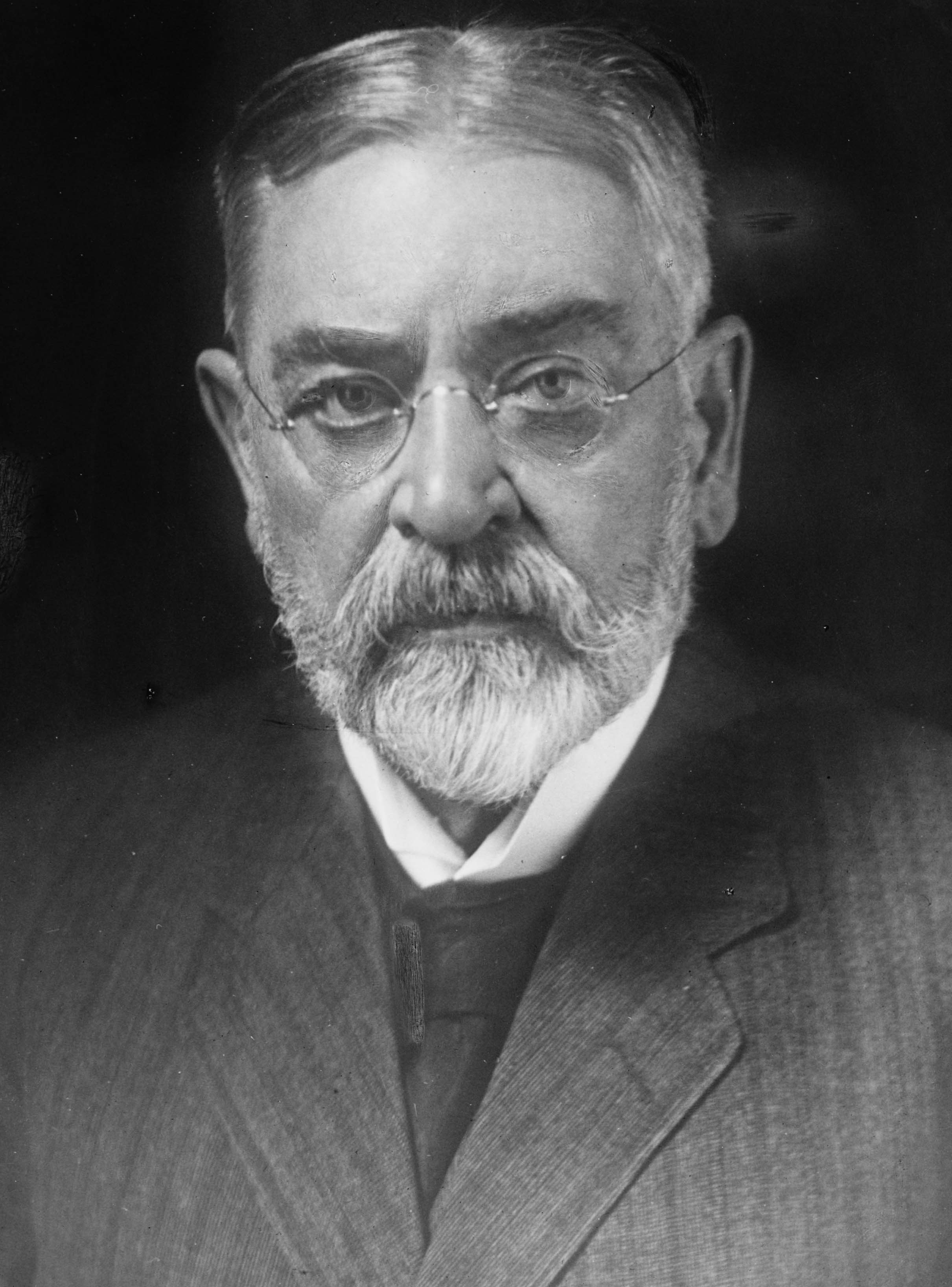

Robert Todd Lincoln and his proximity to 3 out of 4 Presidential Assassinations

Robert Todd Lincoln (August 1, 1843 – July 26, 1926) was an American politician, lawyer, and businessman. Lincoln was the first son of President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln. He was born in Springfield, Illinois and graduated from Harvard College before serving on the staff of Ulysses S. Grant as a captain in the Union Army in the closing days of the American Civil War. After the war Lincoln married Mary Eunice Harlan, and they had three children together. Following completion of law school in Chicago, he built a successful law practice, and became wealthy representing corporate clients.

Active in Republican politics, and a tangible symbol of his father's legacy, Robert Lincoln was often spoken of as a possible candidate for office, including the presidency, but never took steps to mount a campaign. The one office to which he was elected was town supervisor of South Chicago, which he held from 1876 to 1877; the town later became part of the city of Chicago. Lincoln accepted appointments as secretary of war in the administration of James A. Garfield, continuing under Chester A. Arthur, and as United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom (with the role then titled as "minister" ) in the Benjamin Harrison administration.

Lincoln served as general counsel of the Pullman Palace Car Company, and after founder George Pullman died in 1897, Lincoln became the company's president. After retiring from this position in 1911, Lincoln served as chairman of the board until 1922. In Lincoln's later years he resided at homes in Washington, D.C. and Manchester, Vermont; the Manchester home, Hildene, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. In 1922, he took part in the dedication ceremonies for the Lincoln Memorial. Lincoln died at Hildene on July 26, 1926, six days before his 83rd birthday, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

<snip>

Presence at assassinations

Robert Lincoln was coincidentally either present or nearby when three presidential assassinations occurred.

Lincoln was not present at his father's assassination. He was at the White House, and rushed to be with his parents. The president was moved to the Petersen House after the shooting, where Robert attended his father's deathbed.

At President James A. Garfield's invitation, Lincoln was at the Sixth Street Train Station in Washington, D.C., when the president was shot by Charles J. Guiteau on July 2, 1881, and was an eyewitness to the event. Lincoln was serving as Garfield's Secretary of War at the time.

At President William McKinley's invitation, Lincoln was at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, where the president was shot by Leon Czolgosz on September 6, 1901, though he was not an eyewitness to the event; he was just outside the building where the shooting occurred.

Lincoln himself recognized these coincidences. He is said to have refused a later presidential invitation with the comment, "No, I'm not going, and they'd better not ask me, because there is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present."

<snip>

...and a bonus factoid:

Robert Lincoln was once saved from possible serious injury or death by Edwin Booth, whose brother, John Wilkes Booth, was the assassin of Robert's father. The incident took place on a train platform in Jersey City, New Jersey. The exact date of the incident is uncertain, but it is believed to have taken place in late 1863 or early 1864, before John Wilkes Booth's assassination of President Lincoln (April 14, 1865).

Robert Lincoln recalled the incident in a 1909 letter to Richard Watson Gilder, editor of The Century Magazine:

The incident occurred while a group of passengers were late at night purchasing their sleeping car places from the conductor who stood on the station platform at the entrance of the car. The platform was about the height of the car floor, and there was of course a narrow space between the platform and the car body. There was some crowding, and I happened to be pressed by it against the car body while waiting my turn. In this situation the train began to move, and by the motion I was twisted off my feet, and had dropped somewhat, with feet downward, into the open space, and was personally helpless, when my coat collar was vigorously seized and I was quickly pulled up and out to a secure footing on the platform. Upon turning to thank my rescuer I saw it was Edwin Booth, whose face was of course well known to me, and I expressed my gratitude to him, and in doing so, called him by name.

Months later, while serving as an officer on the staff of General Ulysses S. Grant, Robert Lincoln recalled the incident to his fellow officer, Colonel Adam Badeau, who happened to be a friend of Edwin Booth. Badeau sent a letter to Booth, complimenting the actor for his heroism. Before receiving the letter, Booth had been unaware that the man whose life he had saved on the train platform had been the president's son. The incident was said to have been of some comfort to Edwin Booth following his brother's assassination of the president. President Ulysses Grant also sent Booth a letter of gratitude for his action.

Robert was the only child of Abraham and Mary to live to adulthood. There are no direct descendants to Abraham Lincoln alive today. The last, Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith (great grandson of President Lincoln) died in 1985.

Uncle Crock's Block spoke to the cynical kiddies, like me...

Uncle Croc's Block is an hour-long live-action/animated television series. It was produced by Filmation, and broadcast on ABC in 1975–76.

History

As a spoof of kid shows, Charles Nelson Reilly played the eponymous Uncle Croc, a crocodile that hated his job as the show's host. Also featured were Alfie Wise as his rabbit sidekick, Mr. Rabbit Ears, and Jonathan Harris as Basil Bitterbottom, the show-within-a-show's frustrated director. A motorcycle-riding bird named Koo Koo Knievel (a parody of stuntman Evel Knievel) was a motorcycle riding bird that popped out of a clock to announce when it is Star Time.

Star Time

Each episode contained a "Star Time" segment in which parodies of popular characters appeared, usually making denigrating remarks about the show and/or its staff, and demonstrating their abilities (or lack thereof). Guests included:

Captain Klangeroo is a parody of Captain Kangaroo.

Mr. Mean Jeans (played by Huntz Hall) is a parody of Mr. Greenjeans.

Sherlock Domes (played by Carl Ballantine) is a parody of Sherlock Holmes.

Dr. Watkins (played by Stanley Adams) is the sidekick of Sherlock Domes. He is a parody of Dr. Watson.

Witchie Goo Goo (played by Phyllis Diller) is a witch whose prince-conjuring spell always summons a never-willing Basil to her. She is a parody of Witchiepoo from H.R. Pufnstuf.

Junie the Genie (played by Alice Ghostley) is an allegedly teenaged genie. She is a parody of Jeannie from I Dream of Jeannie with a bit of Sabrina the Teenage Witch.

Billy Bratson (played by Marvin Kaplan as Captain Marbles) says "Shazowie" to turn into the superhero Captain Marbles, in the same way Billy Batson transformed into Captain Marvel by saying "Shazam!".

Steve Exhaustion, The $6.95 Man (played by Robert Ridgely) is a cyborg that always falls apart. He is a parody of Steve Austin, The Six Million Dollar Man.

Old Fogey Bear is a manic-depressive bear. He is a parody of Yogi Bear.

Miss Invis is a woman who falsely claims to be able to make herself invisible.

Cartoon segments

The show also included the cartoon shorts:

M*U*S*H (short for Mangy Unwanted Shabby Heroes): Sled dogs (voiced by Kenneth Mars and Robert Ridgely) work at a medical outpost in the frozen wasteland of upper Saboonia. This cartoon is a lampoon of M*A*S*H.

Fraidy Cat: Fraidy Cat (voiced by Alan Oppenheimer) is haunted by the ghosts of eight of his nine lives (each voiced by Lennie Weinrib).

Wacky and Packy: A prehistoric caveman and his pet woolly mammoth (both voiced by Allan Melvin) end up trapped in modern times.

Broadcast history

The series premiered at 10:30 am ET on September 6, 1975. Unfortunately, Uncle Croc's Block was up against the second half of hugely popular The Shazam!/Isis Hour (another Filmation property) and Far Out Space Nuts on CBS. The show, which was fitted with an adult laugh track, was shortened to 30 minutes, then scrapped on February 14, 1976, after half a season on the air.

As a result of the show's poor performance, ABC president Fred Silverman severed all ties with Filmation and began commissioning its Saturday morning cartoons from Hanna-Barbera, with which he had had a working relationship during his time at CBS. In an attempt to save ratings, Filmation had planned to repackage the repeated Groovie Goolies episodes as a new segment, redubbed the Super Fiends (capitalizing on the title of rival Hanna-Barbera's Super Friends), but the show was shelved before the change could be incorporated. The animated segments were featured in the Filmation syndicated package, The Groovie Goolies and Friends, and also resurfaced in the home video market in the 1980s.

I mean, a manic depressive bear???

Profile Information

Member since: Wed Oct 15, 2008, 06:29 PMNumber of posts: 18,770