Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumJapan blocked presentations on nuclear effects at 1955 U.N. confab

GlobalPost

The Japanese government, facing U.S. pressure, moved to block presentations by Japanese scientists about the effects of radioactivity at a U.N. conference on atomic energy in 1955 in Geneva, according to declassified U.S. documents.

The documents highlight the U.S. readiness to promote the "peaceful use" of nuclear power and Japan's stance to toe the U.S. line on the matter despite mounting concern in Japan about radioactivity's possible impact on humans.

Calls were growing in Japan at that time for a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs following the exposure of a Japanese trawler, the Fukuryu Maru No. 5, to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test on Bikini Atoll in the Pacific in 1954. One crew member died later that year.

"The United States was fearful that presentations on nuclear damage would develop into a debate on banning nuclear tests and nuclear weapons use," said Toshihiro Higuchi, an associate lecturer at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who found the documents at the National Archives and Records Administration of the United States.

The case concerned the first meeting of the U.N.-sponsored International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva in August 1955...

http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/kyodo-news-international/140227/japan-blocked-presentations-nuclear-effects-at-1955-un

DreamGypsy

(2,252 posts)...which caused the death of the Japanese fisherman on the "Fortunate Dragon" and many health problems and early deaths for the Marshall Islanders who were also exposed.

An excellent discussion of the blast and its fallout...radioactive, as well as political and social... from The Nuclear Secrecy Blog by Alex Wellerstein is here: Castle Bravo at 60 -

(emphasis mine)

But nobody says something like that unless other things — terrible things — did happen. Two things went wrong. The first is that the bomb was even more explosive than the scientists thought it was going to be. Instead of 6 megatons of yield, it produced 15 megatons of yield, an error of 250%, which matters when you are talking about millions of tons of TNT. The technical error, in retrospect, reveals how grasping their knowledge still was: the bomb contained two isotopes of lithium in the fusion component of the design, and the designers assumed only one of them would be reactive, but they were wrong. The second problem is that the wind changed. Instead of carrying the copious radioactive fallout that such a weapon would produce over the open ocean, where it would be relatively harmless, it instead carried it over inhabited atolls in the Marshall Islands. This necessitated evacuation, long-term health monitoring, and produced terrible long-term health outcomes for many of the people on those islands.

If it had just been natives who were exposed, the Atomic Energy Commission might have been able to keep things hushed up for awhile — but it wasn’t. A Japanese fishing boat, ironically named the Fortunate Dragon, drifted into the fallout plume as well and returned home sick and with a cargo of radioactive tuna. One of the fishermen later died (whether that was because of the fallout exposure or because of the treatment regime is apparently still a controversial point). It became a major site of diplomatic incident between Japan, who resented once again having the distinction of having been irradiated by the United States, and this meant that Bravo became extremely public. Suddenly the United States was, for the first time, admitting it had the capability to make multi-megaton weapons. Suddenly it was having to release information about long-distance, long-term contamination. Suddenly fallout was in the public mind — and its popular culture manifestations (Godzilla, On the Beach) soon followed.

But it’s not just the public who started thinking about fallout differently. The Atomic Energy Commission wasn’t new to the idea of fallout — they had measured the plume from the Trinity test in 1945, and knew that ground bursts produced radioactive debris.

So you’d think that they’d have made lots of fallout studies prior to Castle. I had thought about producing some kind of map with all of the various fallout plumes through the 1950s superimposed on it, but it became harder than I thought — there are just a lot fewer fallout plumes prior to Bravo than you might expect. Why? Because prior to Bravo, they generally did not map downwind fallout plumes for shots in Marshall Islands — they only mapped upwind plumes.

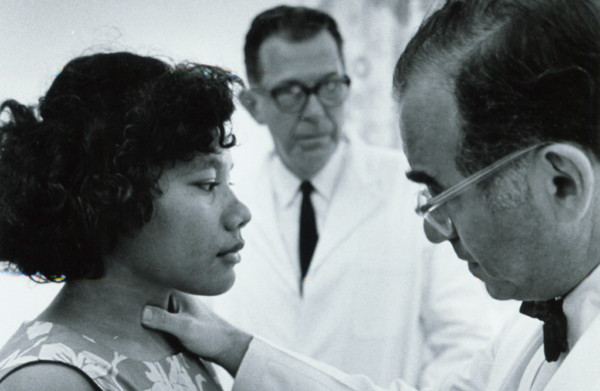

A medical inspection of a Marshallese woman by an American doctor. “Project 4,”

the biomedical effects program of Operation Castle was initially planned to be concerned

with “mainly neutron dosimetry with mice” but after the accident an additional group,

Project 4.1, was added to study the long-term exposure effects in human beings — the Marshallese.

More at the link...

hunter

(38,311 posts)There were Strangelovian military people itching to see what that type of bomb would do to a living city because we'd built the capacity to mass produce these plutonium bombs. And we did mass produce them.

The Manhattan Project was huge. We'd built "120 Fat Man" bombs by April 1949, all were "retired" by late 1950 for better bombs.

The research in Nagasaki was extensive, very detailed, and considered Top Secret, something to keep away from the Soviet Union. This was in Japan's political interest too.

It didn't have a whole lot to do with civilian nuclear power. Cold War secrecy and paranoia infected all high technology at the time.

kristopher

(29,798 posts)...it damned sure had a lot to do with it nonetheless.

hunter

(38,311 posts)Nuclear testing and fear of nuclear weapons was a big, big, deal.

I was a kid in Los Angeles schools. We had two sorts of alarm drills: one for fire when we left the building in an orderly fashion, and the other for nuclear attacks. Upon the special alarm, or upon seeing the flash we were to scramble away from the windows, bend over, and "kiss our ass good-bye." (I first heard that from a worldly sixth grader.)

The first time I saw Helen Caldicott she was all about nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons testing. It was a church group.

When I first "met" her personally she was in the midst of a "what city is this?" tour in a crowd of anti-nuclear activists, and oh, pleased to meet you Hunter. She was promoting this:

https://www.nfb.ca/film/if_you_love_this_planet

I have a funny story, no, not about her, but of the Diablo Canyon anti-nuclear rally where Jerry Brown showed up and said "No New Nukes!" or something like that. (In other words, politico-speak, Diablo Canyon would pass, and be the last, and it was.)

At the time I was working for a boss who played Country-Western music in the warehouse and it was hell. The work was fine, the pay was pretty good, but I hated the music. When the big ships landed we'd sometimes work thirteen hour days if there was a lot of stuff back-ordered. (Bicycle and motorcycle parts, if you care.)

Anyways, after one such long day my boss "rewarded" me with a case of Coors. This was in addition to the time-and-a-half, and then double time, and a generous gift for any boss to give a lowly entry level employee like myself, no matter his poor taste in music and occasionally politics.

So, a few days later, I'm driving my no-nuke colleagues to the rally (one who is still a prominent no-nuker...) and I throw a few of these beers into our ice chest.

We were all listening to the music and the speakers when some people, a woman and a big silent guy, good cop, bad cop, came by to make sure there was no hippy trouble that might cause bad press. They did not approve of the Coors beer in our ice chest, so we dumped it out in the grass.

I've never bought Coors beer in my life, but there it was.

kristopher

(29,798 posts)And as the article clearly states, the public was deprived of pertinent and extremely important information that should have been part of the discussion about setting out on the road to exploit fission for energy.

The public was deceived and the deception favored the creation of a nuclear industry.

The government deliberately lied to people about the dangers associated with the use of nuclear power.

How many ways would you like me to restate an obvious point from the article. Playing the "hey look over here and don't pay any attention to the man behind the curtain" card doesn't really a constitute making a meaningful point.