AsahinaKimi

AsahinaKimi's JournalJAPANESE FOLK TALES ~THE KAKEMONO GHOST OF AKI PROVINCE

DOWN the Inland Sea between Umedaichi and Kure (now a great naval port) and in the province of Aki, there is a small village called Yaiyama, in which lived a painter of some note, Abe Tenko. Abe Tenko taught more than he painted, and relied for his living mostly on the small means to which he had succeeded at his father's death and on the aspiring artists who boarded in the village for the purpose of taking daily lessons from him. The island and rock scenery in the neighbourhood afforded continual study, and Tenko was never short of pupils. Among them was one scarcely more than a boy, being only seventeen years of age. His name was Sawara Kameju, and a most promising pupil he was. He had been sent to Tenko over a year before, when scarce sixteen years of age, and, for the reason that Tenko had been a friend of his father, Sawara was taken under the roof of the artist and treated as if he had been his son.

Tenko had had a sister who went into the service of the Lord of Aki, by whom she had a daughter. Had the child been a son, it would have been adopted into the Aki family; but, being a daughter, it was, according to Japanese custom, sent back to its mother's family, with the result that Tenko took charge of the child, whose name was Kimi. The mother being dead, the child had lived with him for sixteen years. Our story opens with O Kimi grown into a pretty girl.

O Kimi was a most devoted adopted daughter to Tenko. She attended almost entirely to his household affairs, and Tenko looked upon her as if indeed she were his own daughter, instead of an illegitimate niece, trusting her in everything.

After the arrival of the young student O Kimi's heart gave her much trouble. She fell in love with him. Sawara admired O Kimi greatly; but of love he never said a word, being too much absorbed in his study. He looked upon Kimi as a sweet girl, taking his meals with her and enjoying her society. He would have fought for her, and he loved her; but he never gave himself time to think that she was not his sister, and that he might make love to her. So it came to pass at last that O Kimi one day, with the pains of love in her heart, availed herself of her guardian's absence at the temple, whither he had gone to paint something for the priests.

O Kimi leveled up her courage and made love to Sawara. She told him that since he had come to the house her heart had known no peace. She loved him, and would like to marry him if he did not mind.

This simple and maidenlike request, accompanied by the offer of tea, was more than young Sawara was able to answer without acquiescence. After all, it did not much matter, thought he: 'Kimi is a most beautiful and charming girl, and I like her very much, and must marry some day.'

So Sawara told Kimi that he loved her and would be only too delighted to marry her when his studies were complete—say two or three years thence. Kimi was overjoyed, and on the return of the good Tenko from Korinji Temple informed her guardian of what had passed.

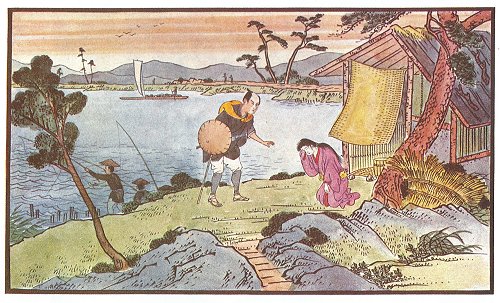

Sawara set to with renewed vigour, and worked diligently, improving very much in his style of painting; and after a year Tenko thought it would do him good to finish off his studies in Kyoto under an old friend of his own, a painter named Sumiyoshi Myokei. Thus it was that in the spring of the sixth year of Kioho—that is, in 1721—Sawara bade farewell to Tenko and his pretty niece O Kimi, and started forth to the capital. It was a sad parting. Sawara had grown to love Kimi very deeply, and he vowed that as soon as his name was made he would return and marry her.

In the olden days the Japanese were even more shockingly poor correspondents than they are now, and even lovers or engaged couples did not write to each other, as several of my tales may show.

After Sawara had been away for a year, it seemed that he should write and say at all events how he was getting on; but he did not do so. A second year passed, and still there was no news. In the meantime there had been several admirers of O Kimi's who had proposed to Tenko

for her hand; but Tenko had invariably said that Kimi-san was already engaged—until one day he heard from Myokei, the painter in Kyoto, who told him that Sawara was making splendid progress, and that he was most anxious that the youth should marry his daughter. He felt that he must ask his old friend Tenko first, and before speaking to Sawara.

Tenko, on the other hand, had an application from a rich merchant for O Kimi's hand. What was Tenko to do? Sawara showed no signs of returning; on the contrary, it seemed that Myokei was anxious to get him to marry into his family. That must be a good thing for Sawara, he thought. Myokei is a better teacher than I, and if Sawara marries his daughter he will take more interest than ever in my old pupil. Also, it is advisable that Kimi should marry that rich young merchant, if I can persuade her to do so; but it will be difficult, for she loves Sawara still. I am afraid he has forgotten her. A little strategy I will try, and tell her that Myokei has written to tell me that Sawara is going to marry his daughter; then, possibly, she may feel sufficiently vengeful to agree to marry the young merchant. Arguing thus to himself, he wrote to Myokei to say that he had his full consent to ask Sawara to be his son-in-law, and he wished him every success in the effort; and in the evening he spoke to Kimi.

'Kimi-chan' he said, 'today I have had news of Sawara through my friend Myokei-san.'

'Oh, do tell me what!' cried the excited Kimi. 'Is he coming back, and has he finished his education? How delighted I shall be to see him! We can be married in April, when the cherry blooms, and he can paint a picture of our first picnic.'

'I fear, Kimi-chan, the news which I have does not talk of his coming back. On the contrary, I am asked by Myokei-san to allow Sawara-san to marry his daughter, and, as I think such a request could not have been made had Sawara been faithful to you, I have answered that I have no objection to the union. And now, as for yourself, I deeply regret to tell you this; but as your uncle and guardian I again wish to impress upon you the advisability of marrying Yorozuya-sama, the young merchant, who is deeply in love with you and in every way a most desirable husband; indeed, I must insist upon it, for I think it most desirable.'

Poor O Kimi-san broke into tears and deep sobs, and without answering a word went to her room, where Tenko thought it well to leave her alone for the night.

In the morning she had gone, none knew whither, there being no trace of her.

Up in Kyoto Sawara continued his studies, true and faithful to O Kimi. After receiving Tenko's letter approving of Myokei's asking Sawara to become his son-in-law, Myokei asked Sawara if he would so honour him. 'When you marry my daughter, we shall be a family of painters, and I think you will be one of the most celebrated ones that Japan ever had.'

'But, sir,' cried Sawara, 'I cannot do myself the honour of marrying your daughter, for I am already engaged—I have been for the last three years—to Kimi-san, Tenko's daughter. It is most strange that he should not have told you!'

There was nothing for Myokei to say to this; but there was much for Sawara to think about. Foolish, perhaps he then thought, were the ways of Japanese in not corresponding more freely. He wrote to Kimi twice, accordingly, but no answer came. Then Myokei fell ill of a chill and died: so Sawara returned to his village home in Aki, where he was welcomed by Tenko, who was now, without O Kimi, lonely in his old age.

When Sawara heard that Kimi had gone away leaving neither address nor letter he was very angry, for he had not been told the reason.

'An ungrateful and bad girl,' said he to Tenko, 'and I have been lucky indeed in not marrying her!'

'Yes, yes,' said Tenko: 'you have been lucky; but you must not be too angry. Women are queer things, and, as the saying goes, when you see water running up hill and hens laying square eggs you may expect to see a truly honest-minded woman. But come now—I want to tell you that, as I am growing old and feeble, I wish to make you the master of my house and property here. You must take my name and marry!'

Feeling disgusted at O Kimi's conduct, Sawara readily consented. A pretty young girl, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, was found—Kiku (the Chrysanthemum);—and she and Sawara lived happily with old Tenko, keeping his house and minding his estate. Sawara painted in his spare time. Little by little he became quite famous. One day the Lord of Aki sent for him and said it was his wish that Sawara should paint the seven beautiful scenes of the Islands of Kabakarijima (six, probably); the pictures were to be mounted on gold screens.

This was the first commission that Sawara had had from such a high official. He was very proud of it, and went off to the Upper and Lower Kabakari Islands, where he made rough sketches. He went also to the rocky islands of Shokokujima, and to the little uninhabited island of Daikokujima, where an adventure befell him.

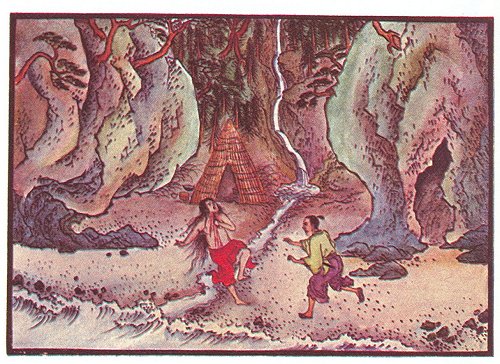

Strolling along the shore, he met a girl, tanned by sun and wind. She wore only a red cotton cloth about her loins, and her hair fell upon her shoulders. She had been gathering shell-fish, and had a basket of them under her arm. Sawara thought it strange that he should meet a single woman in so wild a place, and more so still when she addressed him, saying, 'Surely you are Sawara Kameju—are you not?'

'Yes,' answered Sawara: 'I am; but it is very strange that you should know me. May I ask how you do so?'

'If you are Sawara-san, as I know you are, you should know me without asking, for I am no other than Kimi-chan, to whom you were engaged!'

Sawara was astonished, and hardly knew what to say: so he asked her questions as to how she had come to this lonely island. O Kimi explained everything, and ended by saying, with a smile of happiness upon her face:

'And since, my dearest Sawara-san, I understand that what I was told is false, and that you did not marry Myokei's daughter, and that we have been faithful to each other, we can he married and happy after all. Oh, think how happy we shall be!'

'Alas, alas, my dearest Kimi-chan, it cannot be! I was led to suppose that you had deserted our benefactor Tenko and given up all thought of me. Oh, the sadness of it.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj39.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~ THE PRECIOUS SWORD 'NATORI NO HOTO'

IDE KAMMOTSU was a vassal of the Lord of Nakura town, in Kishu. His ancestors had all been brave warriors, and he had greatly distinguished himself in a battle at Shizugatake, which took its name from a mountain in the province of Omi. The great Hideyoshi had successfully fought in the same place so far back as in the eleventh year of the Tensho Era 1573-1592—that is, 1584—with Shibata Katsuiye. Ide Kammotsu's ancestors were loyal men. One of them as a warrior had a reputation second to none. He had cut the heads off no fewer than forty-eight men with one sword. In due time this weapon came to Ide Kammotsu, and was kept by him as a most valuable family treasure. Rather early in life Kammotsu found himself a widower. His young wife left a son, called Fujiwaka. By and by Kammotsu, feeling lonely, married a lady whose name was Sadako. Sadako later bore a son, who was called Goroh. Twelve or fourteen years after that, Kammotsu himself died, leaving the two sons in charge of Sadako. Fujiwaka was at that time nineteen years of age.

Sadako became jealous of Fujiwaka, knowing him, as the elder son, to be the heir to Kammotsu's property. She tried by every means to put her own son Goroh first.

In the meantime a little romance was secretly going on between a beautiful girl called Tae, daughter of Iwasa Shiro, and young Fujiwaka. They had fallen in love with each other, were holding secret meetings to their hearts' content, and vowing promises of marriage. At last they were found out, and Sadako made their conduct a pretext for driving Fujiwaka out of the house and depriving him of all rights in the family property.

Attached to the establishment was a faithful old nurse, Matsue, who had brought up Fujiwaka from his infancy. She was grieved at the injustice which had been done; but little did she think of the loss of money or of property in comparison with the loss of the sword, the miraculous sword, of which the outcast son was the proper owner. She thought night and day of how she might get the heirloom for young Fujiwaka.

After many days she came to the conclusion that she must steal the sword from the Ihai (shrine—or rather a wooden tablet in the interior of the shrine, bearing the posthumous name of an ancestor, which represents the spirit of that ancestor).

One day, when her mistress and the others were absent, Matsue stole the sword. No sooner had she done so than it became apparent that it would be some months perhaps before she should be able to put it into the hands of the rightful owner. For of Fujiwaka nothing had been heard since his stepmother had driven him out. Fearing that she might be accused, the faithful Matsue dug a hole in the garden near the ayumiya—a little house, such as is kept in every Japanese gentleman's garden for performing the Tea Ceremony in,—and there she put the sword, meaning to keep it hidden until such time as she should be able to present it to Fujiwaka.

Sadako, having occasion to go to the butsudan the day after, missed the sword; and, knowing O Matsue to have been the only servant left in the house at the time, taxed her with the theft of the sword.

Matsue denied the theft, thinking that in the cause of justice it was right of her to do so; but it was not easy to persuade Sadako, who had Matsue confined in an outhouse and gave orders that neither rice nor water was to be given her until she confessed. No one was allowed to go near Matsue except Sadako herself, who kept the key of the shed, which she visited only once every four or five days.

About the tenth day poor Matsue died from starvation. She had stuck faithfully to her resolution that she would keep the sword and deliver it some day to her young master, the lawful heir. No one knew of Matsue's death. The evening on which she had died found Sadako seated in an old shed in a remote part of the garden, and trying to cool herself, for it was very hot.

After she had sat for about half-an-hour she suddenly saw the figure of an emaciated woman with dishevelled hair. The figure appeared from behind a stone lantern, glided along towards the place where Sadako was seated, and looked full into Sadako's face.

Sadako immediately recognised Matsue, and upbraided her loudly for breaking out of her prison.

'Go back, you thieving woman!' said she. 'I have not half finished with you yet. How dare you leave the place where you were locked up and come to confront me?'

The figure gave no answer, but glided slowly along to the spot where the sword had been buried, and dug it up.

Sadako watched carefully, and, being no coward, rushed at the figure of Matsue, intending to seize the sword. Figure and sword suddenly disappeared.

Sadako then ran at top speed to the shed where Matsue had been imprisoned, and flung the door open with violence. Before her lay Matsue dead, evidently having been so for two or three days; her body was thin and emaciated. '

Sadako perceived that it must have been the ghost of O Matsue that she had seen, and mumbled 'Namu Amida Butsu; Namu Amida Butsu,' the Buddhist prayer asking for protection or mercy.

After having been driven from his family home, Ide Fujiwaka had wandered to many places, begging his food. At last he got some small employment, and was able to support himself at a very cheap inn at Umamachi Asakusa Temple.

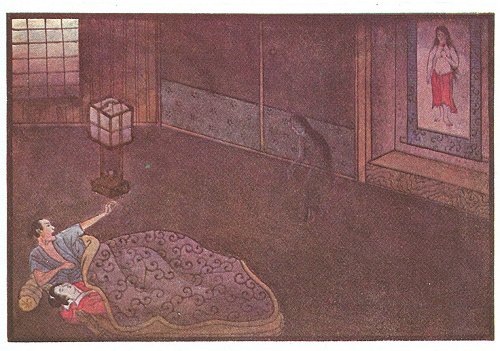

One midnight he awoke and found standing at the foot of his bed the emaciated figure of his old nurse, bearing in her hands the precious sword, the heirloom valued beyond all others. It was wrapped in scarlet and gold brocade, as it had been before, and it was laid reverentially by the figure of O Matsue at Fujiwaka's feet.

'Oh, my dear nurse,' said he, 'how glad am I———' Before he had closed his sentence the figure had disappeared.

My story-teller did not say what became of Sadako or of her son.

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~ THE TEMPLE OF THE AWABI

In Noto Province there is a small fishing-village called Nanao. It is at the extreme northern end of the mainland. There is nothing opposite until one reaches either Korea or the Siberian coast—except the small rocky islands which are everywhere in Japan, surrounding as it were by an outer fringe the land proper of Japan itself.

Nanao contains not more than five hundred souls. Many years ago the place was devastated by an earthquake and a terrific storm, which between them destroyed nearly the whole village and killed half of the people.

On the morning after this terrible visitation, it was seen that the geographical situation had changed. Opposite Nanao, some two miles from the land, had arisen a rocky island about a mile in circumference. The sea was muddy and yellow. The people surviving were so overcome and awed that none ventured into a boat for nearly a month afterwards; indeed, most of the boats had been destroyed. Being Japanese, they took things philosophically. Every one helped some other, and within a month the village looked much as it had looked before; smaller, and less populated, perhaps, but managing itself unassisted by the outside world. Indeed, all the neighbouring villages had suffered much in the same way, and after the manner of ants had put things right again.

The fishermen of Nanao arranged that their first fishing expedition should be taken together, two days before the 'Bon.' ( Bon or Oban: Japanese Buddhist custom to honor the spirits of one's ancestors) They would first go and inspect the new island, and then continue out to sea for a few miles, to find if there were still as many tai fish on their favourite ground as there used to be.

It would be a day of intense interest, and the villages of some fifty miles of coast had all decided to make their ventures simultaneously, each village trying its own grounds, of course, but all starting at the same time, with a view of eventually reporting to each other the condition of things with regard to fish, for mutual assistance is a strong characteristic in the Japanese when trouble overcomes them.

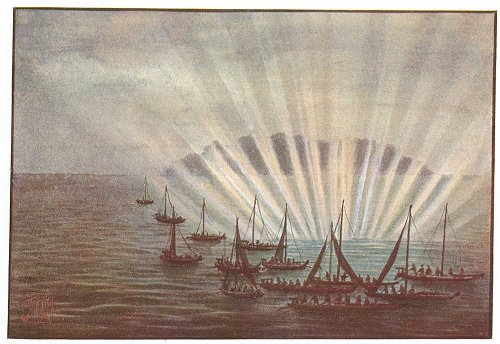

At the appointed time two days before the festival the fishermen started from Nanao. There were thirteen boats. They visited first the new island, which proved to be simply a large rock. There were many rock fish, such as wrasse and sea-perch, about it; but beyond that there was nothing remarkable. It had not had time to gather many shell-fish on its surface, and there was but little edible seaweed as yet. So the thirteen boats went farther to sea, to discover what had occurred to their old and excellent tai grounds.

These were found to produce just about what they used to produce in the days before the earthquake; but the fishermen were not able to stay long enough to make a thorough test. They had meant to be away all night; but at dusk the sky gave every appearance of a storm: so they pulled up their anchors and made for home.

As they came close to the new island they were surprised to see, on one side of it, the water for the space of 240 feet square lit up with a strange light. The light seemed to come from the bottom of the sea, and in spite of the darkness the water was transparent. The fishermen, very much astonished, stopped to gaze down into the blue waters. They could see fish swimming about in thousands; but the depth was too great for them to see the bottom, and so they gave rein to all kinds of superstitious ideas as to the cause of the light, and talked from one boat to the other about it. A few minutes afterwards they had shipped their immense paddling oars and all was quiet. Then they heard rumbling noises at the bottom of the sea, and this filled them with consternation—they feared another eruption. The oars were put out again, and to say that they went fast would in no way convey an idea of the pace that the men made their boats travel over the two miles between the mainland and the island.

Their homes were reached well before the storm came on; but the storm lasted for fully two days, and the fishermen were unable to leave the shore.

As the sea calmed down and the villagers were looking out, on the third day cause for astonishment came. Shooting out of the sea near the island rock were rays that seemed to come from a sun in the bottom of the sea. All the village congregated on the beach to see this extraordinary spectacle, which was discussed far into the night.

Not even the old priest could throw any light on the subject. Consequently, the fishermen became more and more scared, and few of them were ready to venture to sea next day; though it was the time for the magnificent sawara (king mackerel), only one boat left the shore, and that belonged to Master Kansuke, a fisherman of some fifty years of age, who, with his son Matakichi, a youth of eighteen and a most faithful son, was always to the fore when anything out of the common had to be done.

Kansuke had been the acknowledged bold fisherman of Nanao, the leader in all things since most could remember, and his faithful and devoted son had followed him from the age of twelve through many perils; so that no one was astonished to see their boat leave alone.

They went first to the tai grounds and fished there during the night, catching some thirty odd tai between them, the average weight of which would be four pounds. Towards break of day another storm showed on the horizon. Kansuke pulled up his anchor and started for home, hoping to take in a hobo line which he had dropped overboard near the rocky island on his way out—a line holding some two hundred hooks. They had reached the island and hauled in nearly the whole line when the rising sea caused Kansuke to lose his balance and fall overboard.

Usually the old man would soon have found it an easy matter to scramble back into the boat. On this occasion, however, his head did not appear above water; and so his son jumped in to rescue his father. He dived into water which almost dazzled him, for bright rays were shooting through it. He could see nothing of his father, but felt that he could not leave him. As the mysterious rays rising from the bottom might have something to do with the accident, he made up his mind to follow them: they must, he thought, be reflections from the eye of some monster.

It was a deep dive, and for many minutes Matakichi was under water. At last he reached the bottom, and here he found an enormous colony of the awabi (ear-shells). The space covered by them was fully 200 square feet, and in the middle of all was one of gigantic size, the like of which he had never heard of. From the holes at the top through which the feelers pass shot the bright rays which illuminated the sea,—rays which are said by the Japanese divers to show the presence of a pearl. The pearl in this shell, thought Matakichi, must be one of enormous size—as large as a baby's head. From all the awabi shells on the patch he could see that lights were coming, which denoted that they contained pearls; but wherever he looked Matakichi could see nothing of his father.

He thought his father must have been drowned, and if so, that the best thing for him to do would be to regain the surface and repair to the village to report his father's death, and also his wonderful discovery, which would be of such value to the people of Nanao. Having after much difficulty reached the surface, he, to his dismay, found the boat broken by the sea, which was now high. Matakichi was lucky, however. He saw a bit of floating wreckage, which he seized; and as sea, wind, and current helped him, strong swimmer as he was, it was not more than half an hour before he was ashore, relating to the villagers the adventures of the day, his discoveries, and the loss of his dear father.

The fishermen could hardly credit the news that what they had taken to be supernatural lights were caused by ear-shells, for the much-valued ear-shell was extremely rare about their district; but Matakichi was a youth of such trustworthiness that even the most sceptical believed him in the end, and had it not been for the loss of Kansuke there would have been great rejoicing in the village that evening.

Having told the villagers the news, Matakichi repaired to the old priest's house at the end of the village, and told him also.

'And now that my beloved father is dead,' said he, 'I myself beg that you will make me one of your disciples, so that I may pray daily for my father's spirit.'

The old priest followed Matakichi's wish and said, 'Not only shall I be glad to have so brave and filial a youth as yourself as a disciple, but also I myself will pray with you for your father's spirit, and on the twenty-first day from his death we will take boats and pray over the spot at which he was drowned.'

Accordingly, on the morning of the twenty-first day after the drowning of poor Kansuke, his son and the priest were anchored over the place where he had been lost, and prayers for the spirit of the dead were said.

That same night the priest awoke at midnight; he felt ill at ease, and thought much of the spiritual affairs of his flock.

Suddenly he saw an old man standing near the head of his couch, who, bowing courteously, said:

'I am the spirit of the great ear-shell lying on the bottom of the sea near Rocky Island. My age is over thousands of years. Some days ago a fisherman fell from his boat into the sea, and I killed and ate him. This morning I heard your reverence praying over the place where I lay, with the son of the man I ate. Your sacred prayers have taught me shame, and I sorrow for the thing I have done. By way of atonement I have ordered my followers to scatter themselves, while I have determined to kill myself, so that the pearls that are in my shell may be given to Matakichi, the son of the man I ate. All I ask is that you should pray for my spirit's welfare. Farewell!'

Saying which, the ghost of the ear-shell vanished. Early next morning, when Matakichi opened his shutters to dust the front of his door, he found thereat what he took at first to be a large rock covered with seaweed, and even with pink coral. On closer examination Matakichi found it to be the immense ear-shell which he had seen at the bottom of the sea off Rocky Island. He rushed off to the temple to tell the priest, who told Matakichi of his visitation during the night.

The shell and the body contained therein were carried to the temple with every respect and much ceremony. Prayers were said over it, and, though the shell and the immense pearl were kept in the temple, the body was buried in a tomb next to Kansuke's, with a monument erected over it, and another over Kansuke's grave. Matakichi changed his name to that of Nichige, and lived happily.

There have been no ear-shells seen near Nanao since, but on the rocky island is erected a shrine to the spirit of the ear-shell.

NOTE.—A 3000-yen pearl which I know of was sold for 12 cents by a fisherman from the west. It came from a temple, belongs now to Mikomoto, and is this size.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj45.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~THE BLIND BEAUTY

NEARLY three hundred years ago (or, according to my story-teller, in the second year of Kwanei, which would be 1626, the period of Kwanei having begun in 1624 and ended in 1644) there lived at Maidzuru, in the province of Tango, a youth named Kichijiro.

Kichijiro had been born at the village of Tai, where his father had been a native; but on the death of the father he had come with his elder brother, Kichisuke, to Maidzuru. The brother was his only living relation except an uncle, and had taken care of him for four years, educating him from the age of eleven until fifteen; and Kichijiro was very grateful, and determined that now he had reached the age of fifteen he must no longer be a drag on his brother, but must begin to make a way in the world for himself.

After looking about for some weeks, Kichijiro found employment with Shiwoya Hachiyemon, a merchant in Maidzuru. He worked very hard, and soon gained his master's friendship; indeed, Hachiyemon thought very highly of his apprentice; he favoured him in many ways over older clerks, and finally entrusted him with the key of his safes, which contained documents and much money.

Now, Hachiyemon had a daughter of Kichijiro's age, of great beauty and promise, and she fell desperately in love with Kichijiro, who himself was at first unaware of this. The girl's name was Ima, O Ima San, and she was one of those delightful ruddy, happy-faced girls whom only Japan can produce—a mixture of yellow and red, with hair and eyebrows as black as a raven. Ima paid Kichijiro compliments now and then; but he was a boy who thought little of love. He intended to get on in the world, and marriage was a thing which had not yet entered into his mind.

After Kichijiro had been some six months in the employment of Hachiyemon he stood higher than ever in the master's estimation; but the other clerks did not like him. They were jealous. One was specially so. This was Kanshichi, who hated him not only because he was favoured by the merchant but also because he himself loved O Ima, who had given him many a rebuff when he had attempted to make love to her. So great did this secret hate become, at last Kanshichi vowed that he would be revenged upon Kichijiro, and if necessary upon his master Hachiyemon and his daughter O Ima as well; for he was a wicked and scheming man.

One day an opportunity occurred.

Kichijiro had so far secured confidence that the master had sent him off to Kasumi, in Tajima Province, there to negotiate the purchase of a junk. While he was away Kanshichi broke into the room where the safe was kept, and took therefrom two bags containing money in gold up to the value of 200 ryo. He effaced all signs of his action, and went quietly back to his work. Two or three days later Kichijiro returned, having successfully accomplished his mission, and, after reporting this to the master, set to his routine work again. On examining the safe, he found that the 200 ryo of gold were missing, and, he having reported this, the office and the household were thrown into a state of excitement.

After some hours of hunting for the money it was found in a koro (incense-burner) which belonged to Kichijiro, and no one was more surprised than he. It was Kanshichi who had found it, naturally, after having put it there himself; he did not accuse Kichijiro of having stolen the money—his plans were more deeply laid. The money having been found there, he knew that Kichijiro himself would have to say something. Of course Kichijiro said he was absolutely innocent, and that when he had left for Kasumi the money was safe—he had seen it just before leaving.

Hachiyemon was sorely distressed. He believed in the innocence of Kichijiro; but how was he to prove it? Seeing that his master did not believe Kichijiro guilty, Kanshichi decided that he must do something which would render it more or less impossible for Hachiyemon to do otherwise than to send his hated rival Kichijiro away. He went to the master and said:

'Sir, I, as your head clerk, must tell you that, though perhaps Kichijiro is innocent, things seem to prove that he is not, for how could the money have got into his koro? If he is not punished, the theft will reflect on all of us clerks, your faithful servants, and I myself should have to leave your service, for all the others would do so, and you would be unable to carry on your business. Therefore I venture to tell you, sir, that it would be advisable in your own interests to send poor Kichijiro, for whose misfortune I deeply grieve, away.'

Hachiyemon saw the force of this argument, and agreed. He sent for Kichijiro, to whom he said:

'Kichijiro, deeply as I regret it, I am obliged to send you away. I do not believe in your guilt, but I know that if I do not send you away all my clerks will leave me, and I shall be ruined. To show you that I believe in your innocence, I will tell you that my daughter Ima loves you, and that if you are willing, and after you can prove your innocence, nothing would give me greater pleasure than to have you back as my son-in—law. Go now. Try and think how you can prove your innocence. My best wishes go with you.'

Kichijiro was very sad. Now that he had to go, he found that he should more than miss the companionship of the sweet O Ima. With tears in his eyes, he vowed to the father that he would come back, prove his innocence, and marry O Ima; and with O Ima herself he had his first love scene. They vowed that neither should rest until the scheming thief had been discovered, and they were both reunited in such a way that nothing could part them.

Kichijiro went back to his brother Kichisuke at Tai village, to consult as to what it would be best for him to do to re-establish his reputation. After a few weeks, he was employed through his brother's interest and that of his only surviving uncle in Kyoto. There he worked hard and faithfully for four long years, bringing much credit to his firm, and earning much admiration from his uncle, who made him heir to considerable landed property, and gave him a share in his own business. Kichijiro found himself at the age of twenty quite a rich man.

In the meantime calamity had come on pretty O Ima. After Kichijiro had left Maidzuru, Kanshichi began to pester her with attentions. She would have none of him; she would not even speak to him; and so exasperated did he become at last that he used to waylay her. On one occasion he resorted to violence and tried to carry her away by force. Of this she complained to her father, who promptly dismissed him from his service.

This made villain Kanshichi angrier than ever. As the Japanese proverb says, 'Kawaisa amatte nikusa ga hyakubai,'—which means, 'Excessive love is hatred.' So it was with Kanshichi: his love turned to hatred. He thought of how he could be avenged on Hachiyemon and O Ima. The most simple means, he thought, would be to burn down their house, the business offices, and the stores of merchandise: that must bring ruin. So one night Kanshichi set about doing these things and accomplished them most successfully—with the exception that he himself was caught in the act and sentenced to a heavy punishment. That was the only satisfaction which was got by Hachiyemon, who was all but ruined; he sent away all his clerks and retired from business, for he was too old to begin again.

With just enough to keep life and body together, Hachiyemon and his pretty daughter lived in a little cheap cottage on the banks of the river, where it was Hachiyemon's only pleasure to fish for carp and jakko. For three years he did this, and then fell ill and died. Poor O Ima was left to herself, as lovely as ever, but mournful. The few friends she had tried to prevail on her to marry somebody—anybody, they said, sooner than live alone,—but to this advice the girl would not listen. 'It is better to live miserably alone,' she said, 'than to marry one for whom you do not care; I can love none but Kichijiro, though I shall not see him again.'

O Ima spoke the truth on that occasion, without knowing it, for, true as it is that it never rains but it pours, O Ima was to have more trouble. An eye sickness came to her, and in less than two months after her father's death the poor girl was blind, with no one to attend to her wants but an old nurse who had stuck to her through all her troubles. Ima had barely sufficient money to pay for rice.

It was just at this time that Kichijiro's success was assured: his uncle had given him a half interest in the business and made a will in which he left him his whole property. Kichijiro decided to go and report himself to his old master at Maidzuru and to claim the hand of O Ima his daughter. Having learned the sad story of downfall and ruin, and also of Ima's blindness, Kichijiro went to the girl's cottage. Poor O Ima came out and flung herself into his arms, weeping bitterly, and crying: 'Kichijiro, my beloved! this is indeed almost the hardest blow of all. The loss of my sight was as nothing before; but now that you have come back, I cannot see you, and how I long to do so you can but little imagine! It is indeed the saddest blow of all. You cannot now marry me.'

Kichijiro petted her, and said, 'Dearest Ima, you must not be too hasty in your thoughts. I have never ceased thinking of you; indeed, I have grown to love you desperately. I have property now in Kyoto; but should you prefer to do so, we will live here in this cottage. I am ready to do anything you wish. It is my desire to re-establish your father's old business, for the good of your family; but first and before even this we will be married and never part again. We will do that tomorrow. Then we will go together to Kyoto and see my uncle, and ask for his advice. He is always good and kind, and you will like him—he is sure to like you.'

Next day they started on their journey to Kyoto, and Kichijiro saw his brother and his uncle, neither of whom had any objection to Kichijiro's bride on account of her blindness. Indeed, the uncle was so much pleased at his nephew's fidelity that he gave him half of his capital there and then. Kichijiro built a new house and offices in Maidzuru, just where his first master Hachiyemon's place had been. He re-established the business completely, calling his firm the Second Shiwoya Hachiyemon, as is often done in Japan (which adds much to the confusion of Europeans who study Japanese Art, for pupils often take the names of their clever masters, calling themselves the Second, or even the Third or the Fourth).

In the garden of their Maidzuru house was an artificial mountain, and on this Kichijiro had erected a tombstone or memorial dedicated to Hachiyemon, his father-in-law. At the foot of the mountain he erected a memorial to Kanshichi. Thus he rewarded the evil wickedness of Kanshichi by kindness, but showed at the same time that evil-doers cannot expect high places. It is to be hoped that the spirits of the two dead men became reconciled.

They say in Maidzuru that the memorial tombs still stand.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj41.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~WHITE SAKE

Two thousand or more years ago Lake Biwa, in Omi Province, and Mount Fuji, in Suruga Province, came into being in one night. Though my story relates this as fact, you are fully entitled to say, should you feel so inclined, 'Wonderful indeed are the ways of Nature'; but do so respectfully, if you please, and without levity, for otherwise you will grossly offend and will not understand the ethical ideas of Japanese folklore stories.

Well, at the time of this extraordinary geographical event, there lived one Yurine, a man of poor means even for those days. He loved saké wine, and scarcely ever spent a day without drinking some of it. Yurine lived near the place which is now called Sudzukawa, a little to the north of the river known as Fujikawa.

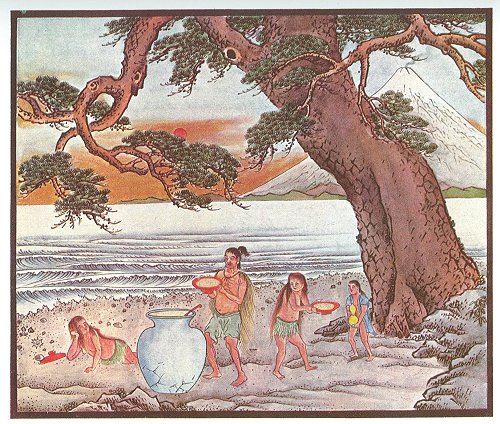

On the day which followed Fuji San's appearance Yurine became ill, and was in consequence unable to drink his cup of saké. He became worse and worse, and, at last feeling that there could be no hope for him, decided to give himself the pleasure of drinking a cup before he died. Accordingly he called to himself his only son, Koyuri, a boy of fourteen years, and told him to go and fetch him a cup or two of the wine. Koyuri was sorely perplexed. He had no saké in the house, and there was not a single coin left wherewith to buy. This he did not like to tell his father, fearing that the unpleasant state of affairs might make him worse. So he took his gourd, and went wandering along the beach, wondering how he could get what his father wanted. While thus employed Koyuri heard a voice calling him by name. As he looked up towards the pines which fringed the beach, he saw a man and a woman sitting beneath an immense tree; their hair was a scarlet red, and so were their bodies. At first Koyuri was afraid,—he had never seen their like before,—but the voice was kindly, and the man was making signs to him to approach. Koyuri did so in fear and trembling, but with that coolness which characterises the Japanese boy.

As Koyuri approached the strange people he noticed that they were drinking saké from large flat cups known as 'sakadzuki,' and that on the sand beside them was an immense jar, from which they took the liquor; moreover, he noticed that the saké was whiter than any he had seen before.

Thinking always of his father, Koyuri unslung his gourd, reported his father's illness, and begged for saké. The red man took the gourd, and filled it. After expressing gratitude, Koyuri ran off delighted. 'Here, father, here!' said he as he reached his hut: 'I have got you the saké, the best I have ever seen, and I am sure it tastes as good as it looks; try it and tell me!'

The old man took the wine and drank greedily, expressing great satisfaction, and said that it was indeed the best he had ever tasted. Next day he wanted more. The boy found his two red friends, and again they filled the gourd. In short, Koyuri had his gourd filled for five days in succession, and his father had regained spirits and was almost well in consequence.

Now, there lived in the next hut to Yurine an unpleasant neighbour who also was fond of saké, but too poor to procure it. His name was Mamikiko. On hearing that Yurine had been drinking saké for the last five days he became furiously jealous, and, calling Koyuri, asked where and how he had procured it. The boy explained that he had got it from the strange people with red hair who had been living near the big pine tree for some days past.

'Give me your gourd to taste,' cried Mamikiko, snatching it roughly. 'Do you think that your father is the only man who is good enough for saké?' Putting the gourd to his lips, he began to drink; but he threw it down in disgust a second later, and spat out what was in his mouth. 'What filth is this?' he cried. 'To your father you give the most excellent saké, while to me you give foul water! What is the meaning of it?' He gave Koyuri a sound beating, and then told him to lead the way to the red people on the beach, saying, 'I will beat you again if I don't get some good saké; so you had better see to it!'

Koyuri led the way, weeping the while at the loss of his saké, which Mamikiko had thrown away, and fearing the anger of his red friends. In the usual place they found the strangers, who had both been drinking and were still doing so. Mamikiko was surprised at their appearance: he had seen nothing quite like them before. Their bodies were of the pink of cherry blossom shining in the sun, while their long red hair almost frightened him; both were naked except for a green girdle made of some curious seaweed.

'Well, boy Koyuri, what are you crying about, and why back so soon? Has your father drunk the saké already? If so he must be almost as fond of it as we.'

'No, no: my father has not drunk it; but Mamikiko, here, took it from me and drank some, spitting it out and saying it was not saké; the rest he threw away, and then made me bring him here. May I have some more for my father?' The red man refilled the gourd and told him not to mind, and seemed amused at Koyuri's account of Mamikiko spitting it out.

'I am as fond of saké as any one,' cried Mamikiko: 'will you give me some?'

'Oh, yes; help yourself,' said the red man; 'Help yourself.' Mamikiko filled the largest of the cups, and, putting it to his nose, smelt the fragrance, which was delicious; but as soon as he put it to his lips his face changed, and he had to spit again, for the taste was nauseating.

'What is the meaning of this?' he cried angrily; and the red man answered still more angrily:

'You do not seem to be aware of who I am. Well, I will tell you that I am a shojo of high degree, and I live deep in the bottom of the ocean near the Sea Dragon's Palace. Recently we heard that a sacred mountain had arisen on the edge of the sea, and, as it is a lucky omen, and a sign that the Empire of Japan will exist in perpetuity, I have come here to see it. While enjoying the magnificent scene from Suruga coast I met this good boy Koyuri, who asked for saké for his poor sick old father, and I gave him some. Now, this saké is not ordinary saké, but sacred, and those who drink it live for ever and retain their youth; moreover, it cures all diseases even in the aged. But you must know that any medicine is sometimes a poison, and thus it is that this sweet sacred white saké is good only in taste to the righteous, and bad-tasting and poisonous to the wicked. Thus I know that, as it tastes evil to you, you are an evil and wicked man, selfish and greedy.' And both the shojos laughed at Mamikiko, who, on hearing that the few drops which he must have swallowed would act as poison and soon kill him, began to cry with fear and to regret his conduct. He begged and implored forgiveness and that his life might be spared, and vowed that he would reform if only given a chance. The shojo, drawing some powder from a case, gave it to Mamikiko, and told him to swallow it in some saké; 'for,' said he, 'it is better to repent and reform even in your old age than not at all.'

Mamikiko drank it down this time, finding the wine sweet and delicious; it strengthened him and made him feel well, and he reformed and became a good man. He made friends again with Yurine and treated Koyuri well.

Some years later Mamikiko and Yurine built a hut at the southern base of Fuji San, where they brewed white saké from a recipe given them by the shojo, and they gave it to all who suffered from saké poisoning. Both Mamikiko and Yurine lived for 300 years.

In the Middle Ages a man who had heard this story brewed white saké at the foot of Mount Fuji; he made it with rice yeast, and people became very fond of it. Even to-day white saké is brewed somewhere at the foot of the mountain, and is well known as a special liquor belonging to Fuji.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj40.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES- A STORMY NIGHT'S TRAGEDY

ALL who have read anything of Japanese history must have heard of Saigo Takamori, who lived between the years 1827 and 1877. He was a great Imperialist, fighting for the Emperor until 1876, when he gave over owing to his disapproval of the Europeanisation going on in the country and the abandonment of ancient national ways. As practical Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Army, Saigo fled to Kagoshima, where he raised a body of faithful followers, which was the beginning of the Satsuma Rebellion. The Imperialists defeated them, and in September of 1877 Saigo was killed—some say in the last battle, and others that he did 'seppuku,' and that his head was cut off and secretly buried, so that it should not fall into the hands of his enemies. Saigo Takamori was highly honored even by the Imperialists. It is hard to call him a rebel. He did not rebel against his Emperor, but only against the revolting idea of becoming Europeanised. Who can say that he was not right? He was a man of fine sentiment and great loyalty. Should all of us follow meekly the Imperial order in England if we were told that we were to practise the manners and customs of South Sea Islanders? That would be hardly less revolting to us than Europeanisation was to Saigo.

In the first year of Meiji 1868 the Tokugawa army had been badly beaten by Saigo at Fushimi, and Field-Marshal Tokugawa Keiki had the greatest difficulty in getting down to the sea and escaping to Edo (Tokyo). The Imperial army proceeded along the Tokaido road, determined to break up the Tokugawa force. Their advance guard had reached Hiratsuka, under Mount Fuji, on the coast.

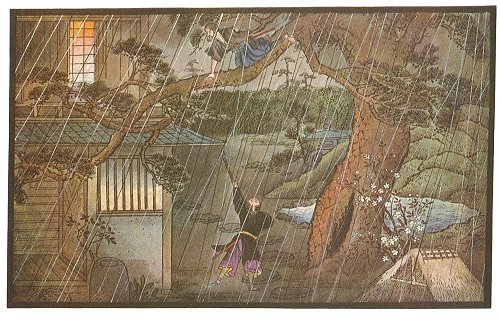

It was a spring day, the 5th of April, and the cherry trees were in full bloom. The country folk had come in to see the victorious troops, who formed the advance guard of those who had beaten the Tokugawa. There were many beggars about, together with pedlars and sellers of sweets, roasted potatoes, and what-not. Towards evening clouds came over the skies; at five o'clock rain began; at six every one was under cover.

At the principal inn were a party of the Headquarters’ Staff officers, including the gallant Saigo. They were making the best of the bad weather, and not feeling particularly lively, when they heard the soft and melodious notes of the shakuhachi (flute) at the gate.

'That is the poor blind beggar we saw playing near the temple to-day,' said one. 'Yes: so it is,' said another. 'The poor fellow must be very wet and miserable. Let us call him in.'

'A capital idea,' assented all of them, among whom was Saigo Takamori. 'We will have him in and raise a subscription for him if he can raise our spirits in this weather.' They gave the landlord an order to admit the blind flute-player.

The poor man was led in by a side door and brought into the presence of the officers. 'Gentlemen,' said he, you have done me a very great honor, and a kindness, for it is not pleasant to stand outside playing in the rain with cotton clothes on. I think I can repay you, for I am said to play the shakuhachi well. Since I have been blind it has become my only pleasure, and not only that but also my only means of living. It is hard now in these unsettled days, when everything is upside-down, to earn a living. Not many travellers come to the inns while the Imperial troops occupy them. These are hard days, gentlemen.'

'They may be hard days for you, poor blind fellow; but say nothing against the Imperial troops, for we have to be suspicious, there being spies of the Tokugawa. Three eyes, indeed, does each of us need in his head.'

'Well, well, I have no wish to say anything against the Imperial troops,' said the blind man. 'All I have to say is that it is precious hard for a blind man to earn enough rice wherewith to fill his stomach. Only once a-week on an average am I called to play to private parties or to shampoo some rheumatic person such as this wet weather produces—the blessing of the Gods be on it!'

'Well, we will see what we can do for you, poor fellow,' said Saigo. 'Go round the room, and see what you can collect, and then we will start the concert.'

Matsu~ichi did as he was bid, and returned to Saigo some ten minutes later with five or six yen, to which Saigo added, saying:

'There, poor fellow: what do you think of that? Say no more that the Imperial troops cause you to have an empty belly. Say, rather, that if you lived near them long the skin of your belly might become so overstretched as to cause you perforce to open your eyes, and then indeed you might find yourself put about for a trade. But let us hear your music. We are dull of spirit to-night, and want enlivening.'

'Oh, gentlemen, this is too much, far too much, for my poor music! Take some of it back.'

'No, no,' they answered. 'We are troops and officers of the Imperial Army: our lives are uncertain from day to day. It is a pleasure to give, and to enjoy music when we can.'

The blind man began to play, and he played long and late. Sometimes his airs were lively, and at other times as mournful as the spring wind which blew through the cherry trees; but his manner was enchanting, and all were grateful to him for having afforded a night's amusement. At eleven o'clock the concert finished and they went to rest; the blind beggar left the inn; and Kato Shichibei, the proprietor, locked it up, in spite of the sentries posted outside.

The inn was surrounded by hedges, and several clumps of bamboos stood in the corners. At the far end was an artificial mountain with a lake at its foot, and near the lake a little summer-house over which towered a huge and ancient pine tree, one of the branches of which stretched right back over the roof of the inn. At about one o'clock in the morning the form of a man might have been seen stealthily climbing this huge tree until he had reached the branch which hung over the inn. There he stretched himself flat, and began squirming along, evidently intent upon reaching the upper floor of the house. Unfortunately for himself, he cracked a small branch of dead wood, and the sound caused a sentry to look up. 'Who goes there?' cried he, bringing his musket round; but there was no answer. The sentry shouted for help, and it was not more than twenty seconds before the whole house was up and out. No escape for the man on the tree was possible. He was taken prisoner. Imagine the astonishment of all when they found that he was the blind beggar, but now not blind at all; his eyes flashed fire of indignation at his captors, for the great plan of his young life was dead.

'Who is he?' cried one and all, 'and why the trickery of being blind last evening?'

'A spy—that is what he is! A Tokugawa spy,' said one. 'Take him to Headquarters, so that the chief officers may interrogate him; and be careful to hold his hands, for he has every appearance of being a samurai and a fighter.'

And so the prisoner was led off to the Temple of Hommonji, where the Headquarters of the Staff temporarily were.

The prisoner was brought into the presence of Saigo Takamori and four other Imperial officers, one of whom was Katsura Kogoro. He was made to kneel. Then Saigo, who was the Chief, said, 'Hold your head up and give us your name.'

The prisoner answered:

'I am Watanabe Tatsuzo. I am one of those who have the honor of belonging to the bodyguard of the Tokugawa Government.'

'You are bold,' said Saigo. 'Will you have the goodness to tell us why you have been masquerading as a blind beggar, and why you were caught in an attempt to break into the inn?'

'I found that the Imperial Ambassador was sleeping there, and our cause is not bettered by killing ordinary officers!'

'You are a fool,' answered Saigo. 'How much better would you find yourself off if you killed Yanagiwara, Hashimoto, or Katsura?'

'Your question is stupid,' was the unabashed answer. 'Every man of us does his little. My efforts are only a fragment; but little by little we shall gain our ends.'

'Have you a comrade here?' asked Saigo.

'Oh, no,' answered the prisoner. 'We act individually as we think best for the cause. It was my intention to kill any one of importance whose death might strengthen us. I was acting entirely as I thought best.'

And Saigo said:

'Your loyalty does you credit, and I admire you for that; but you should recognise that after the last victory of the Imperial troops at Fushimi the Tokugawa's tenure of office, extending over three hundred years, has come to an end. It is only natural that the Imperial family should return to power. Your intention is presumably to support a power that is finished. Have you never heard the proverb which says that "No single support can hold a falling tower"? Now tell me truthfully the absurd ideas which appear to exist in your mind. Do you really think that the Tokugawa have any further chance?'

'If you were any other than the heroic or admirable Saigo I should refuse to answer these questions,' said the prisoner; 'but, as you are the great Saigo Takamori and I admire your loyalty and courage, I will confess that after our defeat some two hundred of us samurai formed into a society swearing to sacrifice our lives to the cause in any way that we were able. I regret to say that nearly all ran away, and that I am (as far as I am able to judge) about the only one left. As you will execute me, there will be none.'

'Stop,' cried Saigo: 'say no more. Let me ask you: Will you not join us? Look upon the Tokugawa as dead. Too many faithful but ignorant samurai have died for them. The Imperial family must reign: nine-tenths of the country demand it. Though your guilt stands confessed, your loyalty is admirable, and we should gladly take you to our side. Think before you answer.'

No thought was necessary. Watanabe Tatsuzo answered instantly.

'No—never. Though alone, I will not be unfaithful to my cause. You had better behead me before the day dawns. I see the strength of your arguments that the Imperial family must and should reign; but that cannot alter my decision with regard to my own fate;

Saigo stood up and said:

'Here is a man whom we must respect. There are many Tokugawa who have joined our cause through fear; but they retain hate in their hearts. Look, all of you, at this Watanabe, and forget him not, for he is a noble man and true to the death.' So saying, Saigo bowed to Watanabe, and then, turning to the guard, said:

'Take the prisoner to the Sambon matsu, and behead him as soon as the day dawns.'

Watanabe Tatsuzo was led forth and executed accordingly.

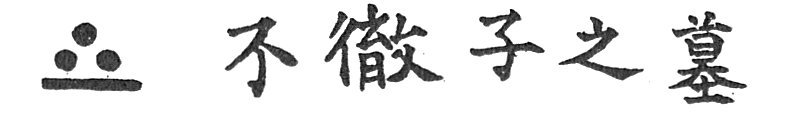

There is a cross-road on the way leading to Mariko, to the right of the Nitta Ferry, some five or six cho from the hill where is the Hommonji Temple, Ikegami, in Ebaragun, Tokio fu, where there is a little grave with a tombstone over it and the characters:

written thereon. They mean Tomb of Futetsu-shi, and it is here that Watanabe Tatsuzo is said to have been buried.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj38.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES-THE SECRET OF IIDAMACHI POND

IN the first year of Bunkiu, 1861-1864, there lived a man called Yehara Keisuke in Kasumigaseki, in the district of Kojimachi. He was a hatomoto—that is, a feudatory vassal of the Shogun—and a man to whom some respect was due; but apart from that, Yehara was much liked for his kindness of heart and general fairness in dealing with people. In Iidamachi lived another hatomoto, Hayashi Hayato.

He had been married to Yehara's sister for five years. They were exceedingly happy; their daughter, four years old now, was the delight of their hearts. Their cottage was rather dilapidated; but it was Hayashi's own, with the pond in front of it, and two farms, the whole property comprising some two hundred acres, of which nearly half was under cultivation. Thus Hayashi was able to live without working much. In the summer he fished for carp; in the winter he wrote much, and was considered a bit of a poet.

At the time of this story, Hayashi, having planted his rice and sweet potatoes (sato-imo), had but little to do, and spent most of his time with his wife, fishing in his ponds, one of which contained large suppon (terrapin turtles) as well as koi (carp). Suddenly things went wrong.

Yehara was surprised one morning to receive a visit from his sister O Komé.

'I have come, dear brother,' she said, 'to beg you to help me to obtain a divorce or separation from my husband.'

'Divorce! Why should you want a divorce? Have you not always said you were happy with your husband, my dear friend Hayashi? For what sudden reason do you ask for a divorce? Remember you have been married for five years now, and that is sufficient to prove that your life has been happy, and that Hayashi has treated you well.'

At first O Komé would not give any reason why she wished to be separated from her husband; but at last she said:

'Brother, think not that Hayashi has been unkind. He is all that can be called kind, and we deeply love each other; but, as you know, Hayashi's family have owned the land, the farms on one of which latter we live, for some three hundred years. Nothing would induce him to change his place of abode, and I should never have wished him to do so until some twelve days ago.'

'What has happened within these twelve wonderful days?' asked Yehara.

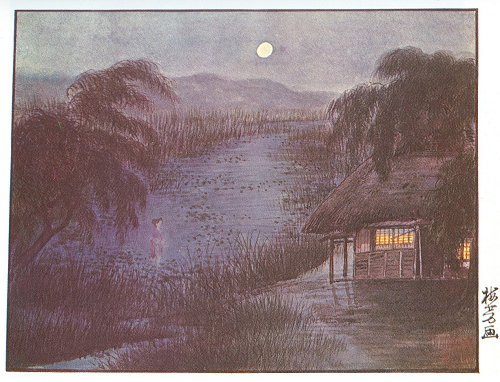

'Dear brother, I can stand it no longer,' was his sister's answer. 'Up to twelve days ago all went well; but then a terrible thing happened. It was very dark and warm, and I was sitting outside our house looking at the clouds passing over the moon, and talking to my daughter.

Suddenly there appeared, as if walking on the lilies of the pond, a white figure. Oh, so white, so wet, and so miserable to look at! It appeared to arise from the pond and float in the air, and then approached me slowly until it was within ten feet.

As it came my child cried: "Why, mother, there comes O Sumi—do you know O Sumi?" I answered her that I did not, I think; but in truth I was so frightened I hardly know what I said. The figure was horrible to look at. It was that of a girl of eighteen or nineteen years, with hair dishevelled and hanging loose, over white and wet shoulders. Help me! help me!" cried the figure, and I was so frightened that I covered my eyes and screamed for my husband, who was inside.

He came out and found me in a dead faint, with my child by my side, also in a state of terror. Hayashi had seen nothing. He carried us both in, shut the doors, and told me I must have been dreaming. "Perhaps," he sarcastically added, "you saw the kappa which is said to dwell in the pond, but which none of my family have seen for over one hundred years."

That is all that my husband said on the subject. The next night, however, when in bed, my child seized me suddenly, crying in terror-stricken tones, "O Sumi—here is O Sumi—how horrible she looks! Mother, mother, do you see her?" I did see her. She stood dripping wet within three feet of my bed, the whiteness and the wetness and the dishevelled hair being what gave her the awful look which she bore. "Help me! Help me!" cried the figure, and then disappeared. After that I could not sleep; nor could I get my child to do so.

On every night until now the ghost has come—O Sumi, has my child calls her. I should kill myself if I had to remain longer in that house, which has become a terror to myself and my child. My husband does not see the ghost, and only laughs at me; and that is why I see no way out of the difficulty but a separation.'

Yehara told his sister that on the following day he would call on Hayashi, and sent his sister back to her husband that night.

Next day, when Yehara called, Hayashi, after hearing what the visitor had to say, answered:

'It is very strange. I was born in this house over twenty years ago; but I have never seen the ghost which my wife refers to, and have never heard about it. Not the slightest allusion to it was ever made by my father or mother. I will make inquiries of all my neighbours and servants, and ascertain if they ever heard of the ghost, or even of any one coming to a sudden and untimely end. There must be something: it is impossible that my little child should know the name Sumi," she never having known any one bearing it.'

Inquiries were made; but nothing could be learned from the servants or from the neighbours. Hayashi reasoned that, the ghost being always wet, the mystery might be solved by drying up the pond—perhaps to find the remains of some murdered person, whose bones required decent burial and prayers said over them.

The pond was old and deep, covered with water plants, and had never been emptied within his memory. It was said to contain a kappa (mythical beast, half-turtle, half-man). In any case, there were many terrapin turtle, the capture of which would well repay the cost of the emptying.

The bank of the pond was cut, and next day there remained only a pool in the deepest part; Hayashi decided to clear even this and dig into the mud below.

At this moment the grandmother of Hayashi arrived, an old woman of some eighty years, and said:

'You need go no farther. I can tell you all about the ghost. O Sumi does not rest, and it is quite true that her ghost appears. I am very sorry about it, now in my old age; for it is my fault—the sin is mine. Listen and I will tell you all.'

Every one stood astonished at these words, feeling that some secret was about to be revealed.

The old woman continued:

'When Hayashi Hayato, your grandfather, was alive, we had a beautiful servant girl, seventeen years of age, called O Sumi. Your grandfather became enamoured of this girl, and she of him. I was about thirty at that time, and was jealous, for my better looks had passed away. One day when your grandfather was out I took Sumi to the pond and gave her a severe beating. During the struggle she fell into the water and got entangled in the weeds; and there I left her, fully believing the water to be shallow and that she could get out.

She did not succeed, and was drowned. Your grandfather found her dead on his return. In those days the officials were not very particular with their inquiries. The girl was buried; but nothing was said to me, and the matter soon blew over. Fourteen days ago was the fiftieth anniversary of this tragedy. Perhaps that is the reason of O Sumi's ghost appearing; for appear she must, or your child could not have known of her name. It must be as your child says, and that the first time she appeared Sumi communicated her name.'

The old woman was shaking with fear, and advised them all to say prayers at O Sumi's tomb. This was done, and the ghost has been seen no more. Hayashi said:

'Though I am a samurai, and have read many books, I never believed in ghosts; but now I do.'

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj42.htm

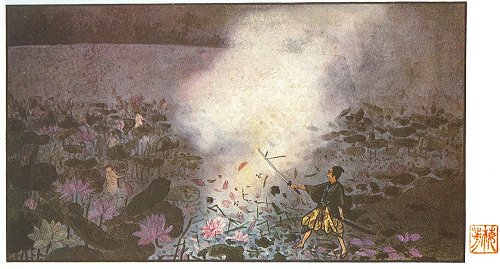

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~THE SPIRIT OF THE LOTUS LILY

FOR some time I have been hunting for a tale about the lotus lily. My friend Fukuga has at last found one which is said to date back some two hundred years. It applies to a castle that was then situated in what was known as Kinai, now incorporated into what may be known as the Kyoto district. Probably it refers to one of the castles in that neighbourhood, though I myself know of only one, which is now called Nijo Castle.

Fukuga (who does not speak English) and my interpreter made it very difficult for me to say that the story does not really belong to a castle in the province of Idzumi, for after starting it in Kyoto they suddenly brought me to Idzumi, making the hero of it the Lord of Koriyama. In any case, I was first told that disease and sickness broke out in Kinai (Kyoto). Thousands of people died of it. It spread to Idzumi, where the feudal Lord of Koriyama lived, and attacked him also. Doctors were called from all parts; but it was no use. The disease spread, and, to the dismay of all, not only the Lord of Koriyama but also his wife and child were stricken.

There was a panic terror in the country—not that the people feared for themselves, but because they were in dread that they might lose their lord and his wife and child. The Lord Koriyama was much beloved. People flocked to the castle. They camped round its high walls, and in its empty moats, which were dry, there having been no war for some time.

One day, during the illness of this great family, Tada Samon, the highest official in the castle (next to the Lord Koriyama himself), was sitting in his room, thinking what was best to be done on the various questions that were awaiting the Daimio's recovery. While he was thus engaged, a servant announced that there was a visitor at the outer gate who requested an interview, saying that he thought he could cure the three sufferers.

Tada Samon would see the caller, whom the servant shortly after fetched.

The visitor turned out to be a yamabushi (mountain recluse) in appearance, and on entering the room bowed low to Samon, saying

'Sir, it is an evil business—this illness of our lord and master—and it has been brought about by an evil spirit, who has entered the castle because you have put up no defence against impure and evil spirits. This castle is the centre of administration for the whole of the surrounding country, and it was unwise to allow it to remain un-fortified against impure and evil spirits. The saints of old have always told us to plant the lotus lily, not only in the one inner ditch surrounding a castle, but also in both ditches or in as many as there be, and, moreover, to plant them all around the ditches. Surely, sir, you know that the lotus, being the most emblematic flower in our religion, must be the most pure and sacred; for this reason it drives away uncleanness, which cannot cross it. Be assured, sir, that if your lord had not neglected the northern ditches of his castle, but had kept them filled with water, clean, and had planted the sacred lotus, no such evil spirit would have come as the present sent by Heaven to warn him. If I am allowed to do so, I shall enter the castle to-day and pray that the evil spirit of sickness leave; and I ask that I may be allowed to plant lotuses in the northern moats. Thus only can the Lord of Koriyama and his family be saved.'

Samon nodded in answer, for he now remembered that the northern moats had neither lotus nor water, and that this was partly his fault—a matter of economy in connection with the estates. He interviewed his master, who was more sick than ever. He called all the Court officials. It was decided that the yamabushi should have his way. He was told to carry out his ideas as he thought best. There was plenty of money, and there were hundreds of hands ready to help him—anything to save the master.

The yamabushi washed his body, and prayed that the evil spirit of sickness should leave the castle. Subsequently he superintended the cleansing and repairing of the northern moats, directing the people to fill them with water and plant lotuses. Then he disappeared mysteriously—vanished almost before the men's eyes. Wonderingly, but with more energy than ever, the men worked to carry out the orders. In less than twenty-four hours the moats had been cleaned, repaired, filled, and planted.

As was to be expected, the Lord Koriyama, his wife, and son became rapidly better. In a week all were able to be up, and in a fortnight they were as well as ever they had been.

Thanksgivings were held, and there were great rejoicings all over Idzumi. Later, people flocked to see the splendidly-kept moats of lotuses, and the villagers went so far as to rename among themselves the castle, calling it the Lotus Castle.

Some years passed before anything strange happened. The Lord Koriyama had died from natural causes, and had been succeeded by his son, who had neglected the lotus roots. A young samurai was passing along one of the moats. This was at the end of August, when the flowers of the lotus are strong and high. The samurai suddenly saw two beautiful boys, about six or seven years of age, playing at the edge of the moat.

'Boys,' said he, 'it is not safe to play so near the edge of this moat. Come along with me.'

He was about to take them by the hand and lead them off to a safer place, when they sprang into the air a little way, smiling at him the while, and fell into the water, where they disappeared with a great splash that covered him with spray.

So astonished was the samurai, he hardly knew what to think, for they did not reappear. He made sure they must be two kappas (mythical animals), and with this idea in his mind he ran to the castle and gave information.

The high officials held a meeting, and arranged to have the moats dragged and cleaned; they felt that this should have been done when the young lord had succeeded his father.

The moats were dragged accordingly from end to end; but no kappa was found. They came to the conclusion that the samurai had been indulging in fancies, and he was chaffed in consequence.

Some few weeks later another samurai, Murata Ippai, was returning in the evening from visiting his sweetheart, and his road led along the outer moat. The lotus blossoms were luxuriant; and Ippai sauntered slowly on, admiring them and thinking of his lady-love, when suddenly he espied a dozen or more of the beautiful little boys playing near the water's edge. They had no clothing on, and were splashing one another with water.

'Ah!' reflected the samurai, 'these, surely, are the kappas, of which we were told before. Having taken the form of human beings, they think to deceive me! A samurai is not frightened by such as they, and they will find it difficult to escape the keen edge of my sword.'

Ippai cast off his clogs, and, drawing his sword, proceeded stealthily to approach the supposed kappas. He approached until he was within some twenty yards; then he remained hidden behind a bush, and stood for a minute to observe.

The children continued their play. They seemed to be perfectly natural children, except that they were all extremely beautiful, and from them was wafted a peculiar scent, almost powerful, but sweet, and resembling that of the lotus lily. Ippai was puzzled, and was almost inclined to sheathe his sword on seeing how innocent and unsuspecting the children looked; but he thought that he would not be acting up to the determination of a samurai if he changed his mind. Gripping his sword with renewed vigour, therefore, he dashed out from his hiding-place and slashed right and left among the supposed kappas.

Ippai was convinced that he had done much slaughter, for he had felt his sword strike over and over again, and had heard the dull thuds of things falling; but when he looked about to see what he had killed there arose a peculiar vapour of all colours which almost blinded him by its brilliance. It fell in a watery spray all round him.

Ippai determined to wait until the morning, for he could not, as a samurai, leave such an adventure unfinished; nor, indeed, would he have liked to recount it to his friends unless he had seen the thing clean through.

It was a long and dreary wait; but Ippai was equal to it and never closed his eyes during the night.

When morning dawned he found nothing but the stalks of lotus lilies sticking up out of the water in his vicinity.

'But my sword struck more than lotus stalks,' thought he. 'If I have not killed the kappas which I saw myself in human form, they must have been the spirits of the lotus. What terrible sin have I committed? It was by the spirits of the lotus that our Lord of Koriyama and his family were saved from death! Alas, what have I done—I, a samurai, whose every drop of blood belongs to his master? I have drawn my sword on my master's most faithful friends! I must appease the spirits by disembowelling myself.'

Ippai said a prayer, and then, sitting on a stone by the side of the fallen lotus flowers, did seppuku.

The flowers continued to bloom; but after this no more lotus spirits were seen.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj44.htm

Profile Information

Name: KimikoGender: Female

Hometown: San Francisco

Home country: USA

Current location: California

Member since: Tue Oct 28, 2008, 06:27 PM

Number of posts: 20,776